The German theatre landscape is characterised by an extraordinary diversity and density of cultural offerings. Historically, this theatre culture, which is unique even by international standards, has developed since the 17th century as a result of the territorial fragmentation of the German dominions in the former Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Court theatres and court chapels were established at numerous larger, medium-sized, and smaller princely courts, and their tradition can be traced back over the centuries to the federal structure of today's Federal Republic of Germany. The repertoire of the court theatres was broad and encompassed the various genres of opera, drama and ballet (dance theatre). Equally typical was the international character of a musical culture that linked German drama with Italian opera as well as with French music and dance theatre. Together with the bourgeois private theatres and the municipal orchestras and community theatres, that had emerged since the 19th century, a dense network of performing arts of astonishing diversity developed.

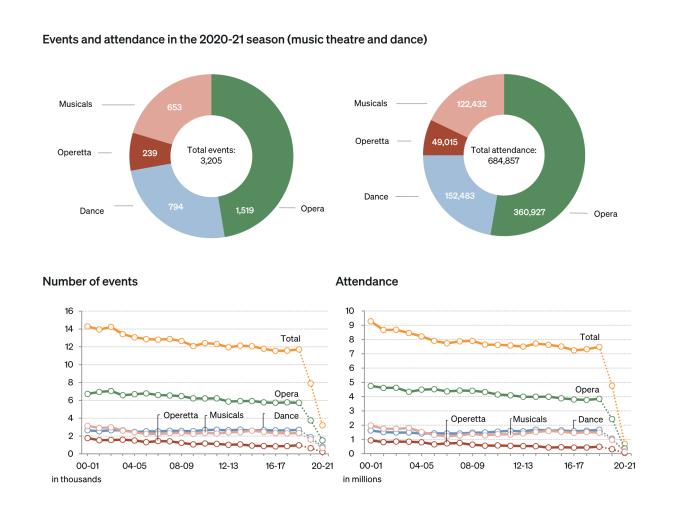

Today, music theatre with its various genres - opera, dance, musical and operetta – is clearly the favourite with Germany’s theatre audiences: The last pre-corona season 2018-19, saw a total of 7.5 million visitors in publicly funded music theatre venues, roughly the same number as in previous seasons. The fact that audience attendance in 2019-20 suffered a massive slump with around 4.8 million visits - of which around 2.4 million were in opera, around one million each in dance theatre and musicals and more than 300,000 in operetta - can be explained by the reduced number of performances and the limited seating capacity due to the Covid-19 pandemic from March 2020 (the number of visitors in spoken theatre was around 3.2 million in the same season). Attendance figures for the following 2020-21 season were even lower, with just under 685,000 people in Germany making their way to the music theatre, according to the German Theatre Association. [1] In contrast to the previous season, which at the beginning was taken place as planned, a month-long lockdown from November 2020 led to a complete cessation of public theatre operations. No statistical data is yet available for the subsequent 2021-22 season, but it is becoming apparent that attendance figures will consolidate at a much higher level once the pandemic is over: Thanks to vaccinations and accompanying hygiene measures, the music theatres were largely able to resume their usual operations from mid-2021, especially after the last corona measures were lifted at the beginning of 2023.

The high demand is met by a dense infrastructure: Germany has 83 publicly financed, fully professional opera houses or opera divisions in multifunctional theatres. These are augmented by many independent ensembles of performing opera, dance and musicals, professional private theatres (especially for musicals) and national and international festivals offering a wide variety of productions. The distribution among Germany’s types of music theatres constitutes what might be called the ‘music theatre market’. Operas make up approximately half of all stage performances; musicals account for another 20 per cent, as do ballet and dance theatre combinded, with operettas making up around 8 per cent (see Fig. 3).

The importance of Germany’s music theatre landscape, becomes clear when viewed in an international context. According to figures from the Operabase platform, 6167 opera and 966 operetta performances took place in Germany during the 2022-23 season – more than in any other country on earth. [2]

The German theatre system

Germany’s theatre system falls into two categories in organisational, institutional and economic terms: publicly funded theatres and private theatres, with the former further sub-divided into state theatres, municipal theatres, and regional theatres (Landestheater). Music theatre plays a prominent role in all three publicly funded theatre forms. Among the private theatres, the individual theatre genres have very different statuses. In the area of music theatre, the musical stages in particular are organised on a purely private basis. In contrast, opera, dance theatre and operetta are heavily dependent on public funding and are therefore mainly offered by theatres run by the federal states and the city authorities.

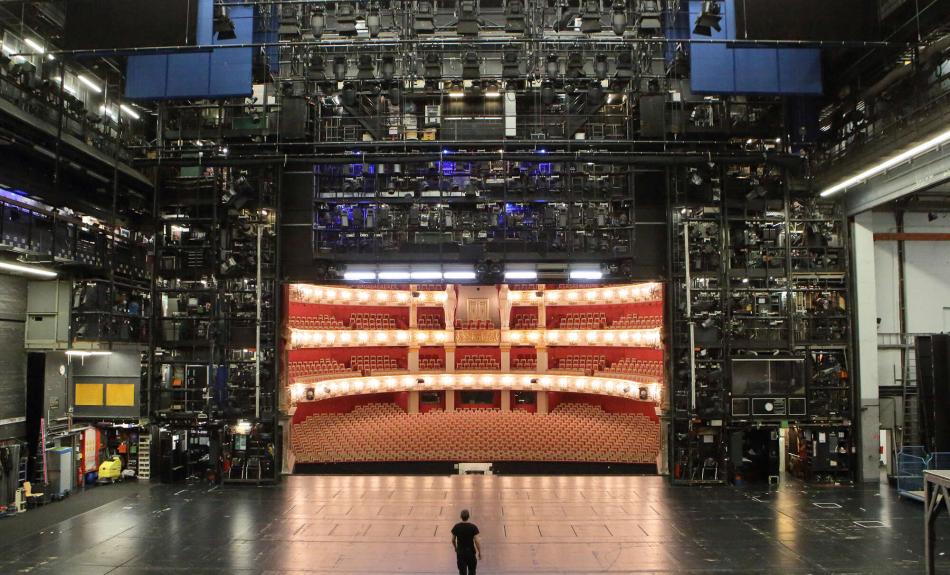

State theatres are those prestigious houses which are, with rare exceptions, wholly owned by one of Germany’s federal states (Länder) and are at least 50 per cent financed from the state’s budget. Most state theatres were originally court or ‘residence’ theatres (i.e. housed in the seat of residence of a ruling family). They are usually keepers of a proud theatrical tradition and can boast of houses with above-average seating capacity and stage size. With the end of the German Empire and its many principalities in 1918, most of the former court theatres became state theatres, with the state governments taking charge of the institutions as legal successors to the former monarchies. State theatres can be found in most of Germany’s federal states, the exceptions being North Rhine-Westphalia, Saxony-Anhalt and Schleswig-Holstein. Owing to historical circumstances (former residences) or cultural-political decisions, many state theatres are not located in today’s state capitals. In addition to Düsseldorf, Magdeburg and Kiel, no state theatres are found in Potsdam and Erfurt. There is a particularly large number of state theatres in the Free State of Bavaria, which, in addition to the theatres in the state capital of Munich, has also recently taken over the sponsorship and partial financing of the former municipal theatres in Augsburg and Nuremberg, thus setting an important cultural policy example.

There are currently 25 state theatres actively producing music theatre in Augsburg, Berlin (Deutsche Oper, Komische Oper, Staatsoper Unter den Linden and Friedrichstadt-Palast), Braunschweig, Bremen, Cottbus, Darmstadt, Dresden, Hamburg, Hanover, Karlsruhe, Kassel, Mainz, Meiningen, Munich (Bavarian State Opera and Gärtnerplatztheater), Nuremberg, Oldenburg, Saarbrücken, Schwerin, Stuttgart, Weimar and Wiesbaden.

Municipal theatre is the most typical kind of theatre in Germany. Municipal theatres are run by the town or city concerned. Currently Germany has 50 municipal theatres or theatres jointly administered by two or more municipalities (Städtebundtheater), each with its own opera divisions. Most of these municipal theatres are multifunctional houses that present music theatre and spoken drama as well as ballet, children's theatre or other genres in the same building. The majority of today's municipal theatres date back to the 19th century, when they were founded as private initiatives and were, for the most part, at least initially run as private businesses. Among the oldest municipal stages are the Mannheim National Theatre (1838) and the Freiburg City Theatre (1868). In 1917, shortly before the German Empire came to an end, there were only 16 municipal theatres operated by city authorities, as opposed to more than 360 private theatres. Soon, however, particularly during the Weimar Republic, many formerly private theatres were taken over by municipal governments. At this point the municipal theatre developed into the centre of cultural display in most of Germany’s large cities. Since the expenses of municipal theatre make up the largest single item in a city’s cultural budget, financial pressure has caused many local and municipal authorities, especially in recent years, to merge theatres in neighbouring cities. This is particularly the case in the eastern states of Germany.

Alongside the state and municipal theatres, the regional theatres form the third tier of publicly funded theatres, although they are of secondary importance for music theatre. Regional theatres are public theatre companies with permanent ensembles and changing venues at different locations, that offer a large proportion of their performances within a defined region outside of their place of production. Most regional theatres originally started as touring companies. It was not until the 1920s that regional theatre became established as an organised branch of theatre. The original homes of these theatres are mainly small and medium-sized towns. At present only the regional theatres in Coburg, Detmold, Flensburg, Halberstadt, Hildesheim, Hof and Radebeul have their own production facilities for music theatre.

‘Due to the diversity, density and quality of its offerings, the German music theatre scene is perceived as a leader and benchmark in international comparison.’

Funding and staffing

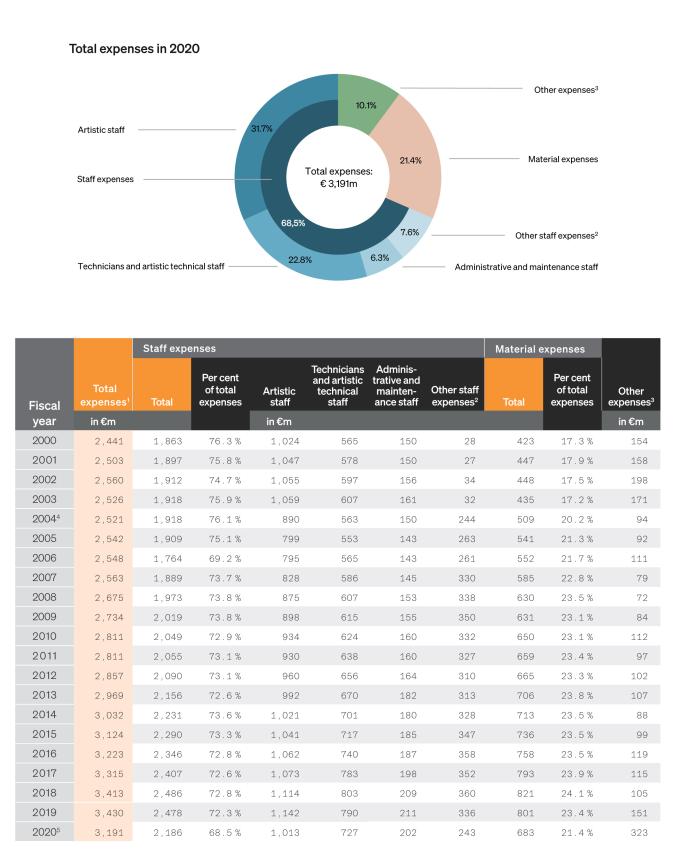

Due to the variety of artistic disciplines involved and the particularly large number of staff required, music theatre is the most expensive form of theatre. Therefore, a particularly high proportion of all public expenditure for culture goes to the funding of theatres and orchestras [3] and music theatres are the ones that require the most. Staff costs make up the largest share of the financial burden, amounting on average to almost three-quarters of the budget. Of this, roughly half is paid to artistic staff and the other half to non-artistic employees (see Fig. 1). The Stuttgart State Theatre, currently Germany’s largest theatrical undertaking in terms of both budget and staff, has almost 1,400 permanent employees in its three departments (opera, ballet, and drama). Even a small opera house will have a payroll running into three figures. It has become a recognised economic fact that opera productions are structurally unable to cover their expenses and need to receive third-party funding. The reasons for this were first examined by the British economists William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen in 1966. [4] In general, the economic dilemma facing the performing arts is the virtual impossibility of increasing productivity in their core area (i.e. stage performances). While the Industrial Revolution has caused immense productivity increases in progressive sectors of the economy over the last two centuries – with correspondingly rapid wage increases – staging a standard repertory opera today still requires more or less the same rehearsal time, the same number of employees and the same number of skilled man-hours that were necessary at the first performances some 150 or 200 years ago. This means that theatres have inevitably needed increasingly large injections of money, which can no longer be offset by raising ticket prices. As a result, according to figures from the German Theatre and Orchestra Association (Deutscher Bühnenverein), every public theatre ticket in the 2018/19 season is subsidised on average by approximately €138. As a result of the theatre closures during the coronavirus pandemic, the subsidy requirement per ticket rose to around €200 in the 2019-20 season and even to just under €1,300 in the 2020-21 season.

These economic conditions are the reason why cost cutting and efficient management alone cannot resolve the structural financial problems of the theatre. Although in recent years most German theatres have sharply cut back costs and consistently exploited opportunities to economise, they have not been able to boost their revenues (i.e. the percentage of total expenses covered by their own proceeds), which have remained on average at almost 18 per cent over the last decade. Conversely, this means that roughly 80 per cent of expenses are not covered by box-office returns and must be made up by subsidies and allocations from the public coffers (in 2022 44.7 per cent from municipalities, 45.8 per cent from states and 0.7 per cent from the federal government). [5] In other words, music theatre companies are inevitably loss-making concerns whose upkeep is only legitimate because they fulfil a cultural mandate. In addition to preserving cultural heritage and promoting contemporary productions, regional and local authorities can justify taking over the funding of theatres because, otherwise, the public need for performances of appropriate quality would be assumed by non-subsidised private businesses, which would mean far higher prices and a much narrower range of productions.

The mere fact of belonging to one of the three types of publicly funded theatre (state, municipal or regional) says little about a theatre’s artistic capabilities or the financial resources of the theatre. The budgets of some of the larger municipal theatres (e.g. Frankfurt, Cologne or Leipzig) can rival those of leading state theatres, while smaller state theatres, such as Meiningen or Oldenburg, are somewhere in the lower mid-range of Germany’s league of opera houses. The annual budget of music theatres depends on the number of permanent employees, the number of productions and performances as well as the fees payable to the staff of a given show. Accordingly, annual budgets vary between a mere €8 to €9 million for smaller establishments (e.g. Luneburg or Annaberg) and €113 million for larger ones (Bavarian State Opera). [6]

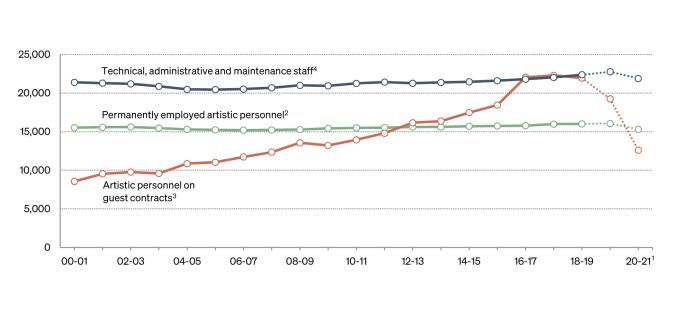

Singers are the heart of any opera, operetta or musical performance, and there is no other stage profession offering a comparable career range. The largest ensembles of singers are employed at Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf and Duisburg (55 members) and the Frankfurt am Main City Theatres (43 members). The number of guest contracts in Germany now far exceeds that of ensemble members: the number of permanent positions dropped further, after a major downturn in the 1990s, and has fallen from 1,462 to 1,182 since the turn of the millennium. At the same time the number of guest contracts (including dance and spoken theatre) has risen from 8,557 to 22,041 (see Fig. 2). This development, which reflects the growing internationalisation of the opera business, poses a danger to Germany’s emphasis on ensemble theatre (see under ‘Types of production’). Career opportunities for soloists in music theatre have declined in recent years, partly due to competition from greater numbers of graduates and young, excellently trained up-and-coming singers from abroad.

Staff numbers in artistic ensembles (orchestra, chorus, ballet), which declined with the merging of orchestras and theatres at the end of the last century, have largely stabilised over the last decade. Grading an orchestra into salary brackets according to the number of permanent positions (category A/F1: more than 130 musicians; A: 99-129 musicians; B: 66-98; C: 56-65 and D: up to 55 musicians) is an important indicator for the artistic capability of a music theatre. [7] Most theatres have a B-level orchestra, i.e. an orchestra large enough to permit performances of the standard opera repertoire without outside assistance. Choruses are also included in the grading of orchestras, meaning that theatres having an A-, B-, C- or D- level orchestra will have a chorus on a corresponding scale. Dance ensembles have suffered greatly from staff cuts since the turn of the millennium, mainly because many theatres shut down their entire dance departments.

In the years 2020 to 2022 the coronavirus pandemic was an extraordinary test of endurance for all theatres and their artistic and non-artistic staff. Overall, however, the German theatre system proved to be surprisingly resilient in this crisis. The high proportion of permanently employed stage artists, orchestral musicians and non-artistic staff mitigated the social hardships and enabled continuity in planning and work processes even during the pandemic. Thanks to the permanent staffing of the theatres, performances could be resumed immediately at the end of each lockdown.

Compared to non-artistic staff (22,765 employees), the artistic staff at German theatres is clearly in the minority, with 16,062 permanently employed workers in the 2019-20 season. Most people employed at German theatres work in various technical capacities. Altogether the number of non-artistic employees has grown by 2,000 positions over the last decade.

Types of production

In addition to the large number of permanent institutions, there are two typical features of the German theatre landscape: the repertory system and the ensemble principle. Both are being eroded by the internationalisation and globalisation of the music markets. German music theatre has traditionally worked with permanent ensembles of singers who have become a tight-knit community over time and have experienced common artistic influences. While large opera houses give many singing roles to international guest soloists, multifunctional theatres tend to recruit soloists from within their standing ensemble. Even if the importance of fixed ensembles has declined slightly in recent decades compared to that of guest soloists, the coronavirus pandemic has also shown the importance of fixed ensembles both for the social security of employees and for the continuity of production processes in the German theatre. These experiences are likely to significantly increase the attractiveness of fixed ensemble engagements for young singers. In addition to the relatively greater security, fixed ensembles offer the opportunity to acquire repertory and stage experience in changing constellations. After studying singing and possibly participating in an opera studio run jointly by the university and the theatre, the ensemble of a municipal or state theatre provide particularly good prospects for starting a career.

The traditional repertory system is typified by continuous operations with daily play changes made possible by a large number of rehearsed and alternating productions. The performance venue is closed for only a few days. This approach presupposes a permanent ensemble, ideally with a suitable singer for each type of role. The main advantages of the repertory system are programme diversity and the artistic quality of an ensemble attuned to each other over a long period of time. The ‘stagione,’ ‘semi-stagione’ and ‘en-suite’ theatre systems have established themselves alongside the repertory system. An exclusively repertory system is virtually unheard of outside the German-speaking countries and some other parts of Central and Eastern Europe.

The Italian word stagione (literally ‘season’) defines a theatrical operation where one production is shown continuously during a given part of the year. Originally the term was used to describe a season which comprised less than a full year, perhaps only a few weeks or months, such as the carnival season, the summer season, the autumn season and others. Both in Italy, its country of origin and in many other countries this principle still holds sway today.

For some time, there has been a heated debate on the relative economic merits of the repertory and the ‘stagione’ systems. Basically, the repertory system allows a far wider range of works. This translates into such an overwhelming advantage in terms of cultural politics that it should not be put at risk by focusing exclusively on economic factors. At the same time, it is useful to compare the two systems from economic and artistic vantage points which reveals the advantages and disadvantages of both systems. The daily rotation of productions in the repertory system means continuous set changes requiring a large number of stage technicians, lighting experts, stage hands etc. Furthermore, the sets need to be stored over longer periods and maintained in the workshops. Simultaneously performing and rehearsing several pieces requires additional rehearsal stages. In contrast, the ‘stagione’ system makes it possible to rehearse with greater concentration and to achieve higher performance quality because of the continuous series of performances. Its significant disadvantages are the limited exploitation of the potential audience and the reduced number of performances per season. In a repertory-type opera house, one and the same production can be seen many times by visitors who return at longer intervals. However, with a ‘stagione’ system, it frequently happens that a production is no longer running by the time word of its high quality has made the rounds. In any case, there are significantly fewer performances per season in a ‘stagione’ system compared with a repertory theatre, because theatres close between show days and have periods of closure between productions.

One tried and tested compromise between the ‘stagione’ and repertory systems is the so-called ‘semi-stagione’ or ‘block system.’ Here the season is divided into several programme blocks, within which a small number of different productions are shown alternately. Most German opera houses have gradually shifted in recent decades from a repertory to a ‘semi-stagione’ system. Theatres using the ‘semistagione’ approach work generally with more guest soloists who are hired specifically according to the requirements of the respective productions.

In Serientheater, or ‘en-suite‘ theatre, the same production is shown continuously over a longer period. Unlike the ‘stagione’ system, ‘en-suite’ theatres operate on the basis of considerably longer runs, which are not initially restricted to a fixed period. ‘En-suite’ productions continue until audience demand dwindles away. This type of operation is limited almost exclusively to the production of commercial musicals, this being the only form of music theatre that can and must achieve the necessary number of performances.

Visits

Among the different types of staged music, opera is the number one crowd puller: a total of 2.4 million visits to around 3,750 opera performances in Germany in the 2019-20 season (see Fig. 3). Ballet and dance theatre come second, numbering some 1.1 million visits, which puts them ahead of musicals with 975,000 and operettas with roughly 312,000 visits per annum. It should be borne in mind that these data must also be seen against the background of the pandemic-related restrictions in music theatre operations and are therefore not representative of the overall development. This applies even more to the particularly noticeable slump in attendance figures for the subsequent 2020-21 season. Since the turn of the millennium until the first pandemic-related lockdown in 2020 it is only in dance theatre that the number of visitors has remained constant, with occasional vacillations. The figures have sharply declined in opera and the musical and have even been halved in the case of operetta. Yet these findings do not reflect a decline in audience interest so much as a substantial reduction in output: the number of performances in music theatre alone has dropped by roughly 2,500 in the first two decades of the 21st century before further slumps occurred in 2020 because of the pandemic. There are various explanations for this decline. First is the above-mentioned gradual shift in many theatres from a repertory to a ‘stagione’ system, for the much larger number of days without performances in the ‘stagione’ or ‘semi-stagione’ system has caused a substantial downturn in overall offerings. Moreover, operations have frequently been limited while theatre buildings are being renovated and venues temporarily closed. The State Opera Unter den Linden in Berlin, for example, was shut down from autumn 2010 to autumn 2017 for general remodelling and had to carry on its operations in the much smaller Schiller Theatre. In the years 2020 to 2022, there were longer theatre closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly distorted the statistics for this period. Another example is the Cologne Oper, whose general remodelling, begun in 2012, was meant to be completed by 2015 but will according to current plans continue until 2024. Here, too, the offerings were radically reduced as operations were transferred to various temporary premises. In the near future the opera houses in Stuttgart and Frankfurt are also slated for general renovation, and new buildings are being discussed as part of the debate on expenditure. Whether and to what extent these developments will have an impact on visitor behaviour is currently difficult to predict.

One important indicator for audience interest in the division of a music theatre is so-called seating capacity utilisation, i.e. the number of visitors in relation to the number auf available seats. Here, however, it should be borne in mind that performances of opera and musicals generally take place in auditoriums with much greater seating capacity than those of dance and operetta. At the same time, the sharp downturn in the number of operetta performances has caused the capacity utilisation in this area to stabilise. Comparing capacity utilisation in season 2019-20 in each sector, we find that musicals score best with 86.2 per cent, followed by dance (82.1 per cent), opera (75.9 per cent) and operetta (73.5 per cent). The capacity utilisation figures recorded for the 2020-21 season are significantly lower than those of the previous season, particularly in the areas of dance (75.8 per cent), operetta (66.6 per cent) and musicals (75.1 per cent), while those for opera have only fallen by 2.5 per cent to 73.4 per cent. However, due to the limited offerings, these figures only represent a snapshot of the attendance situation during the coronavirus pandemic.

Trends in programming

The smaller number of successful contemporary musical works for the stage, unlike spoken theatre, makes for a generally more stable repertoire. This comprises a ‘canon’ of some 50 works by Giuseppe Verdi, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Giacomo Puccini, Gioachino Rossini, Richard Wagner, Georges Bizet, Peter Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss, Gaetano Donizetti, Jacques Offenbach, Charles Gounod, Engelbert Humperdinck, Leos Janáček, Ludwig van Beethoven, Carl Maria von Weber, Bedřich Smetana, Pietro Mascagni, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Georg Friedrich Handel, Vincenzo Bellini and Christoph Willibald Gluck, all of which appear more or less regularly in opera houses worldwide. In addition, there are about 100 to 200 works not only by the composers listed above, but also e.g. Jules Massenet, Claude Debussy, Albert Lortzing, Benjamin Britten, Alexander Borodin, Igor Stravinsky, Franz Schreker, Dmitri Shostakovich, Maurice Ravel and Umberto Giordano. This range is regularly augmented by rediscoveries (recently e.g. Luigi Cherubini, Ambroise Thomas, Mieczysław Weinberg, Karol Szymanowski and Jean-Philippe Rameau) and a few contemporary pieces (e.g. by John Adams, Thomas Adès, Philip Glass, Salvatore Sciarrino and Wolfgang Rihm). [8]

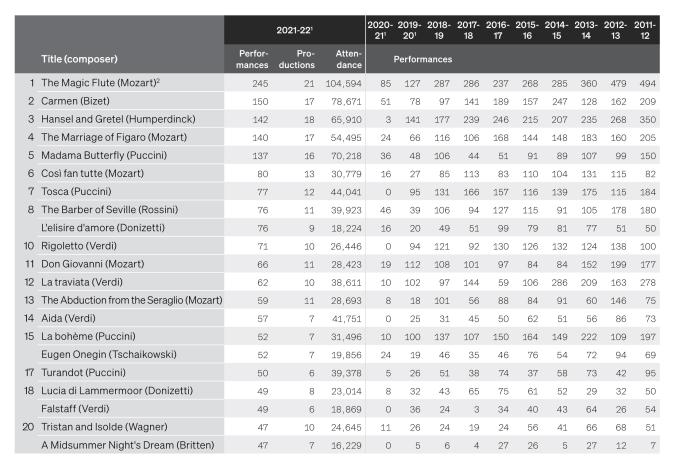

The overview of the operas with the most performances in Germany presents relatively few surprises at the top of the list: The canon of the most popular works has been clearly established in popular art for decades. What is more remarkable, however, is the diversity of operas on offer beyond the very top ranks: here you will find numerous works from the 20th and 21st centuries as well as unusual rediscoveries from the older repertoire that epitomise the vitality and variability of opera as an art form. In the years 2014 to 2019 (the last five seasons before the coronavirus pandemic), well over 800 different operas were performed in Germany alone, including more than 400 contemporary works that premiered after 1945. These figures refute the widespread notion that opera is a ‘museum-like’ art form. Even if the majority of the most frequently performed operas date from the 19th century, more and more recent works have been able to assert themselves on the repertoire in the last years - a development that gives cause for optimism.

In addition to the expansion of the repertoire, the variety of staging styles that can be experienced on German stages is worth noting.

In addition to its theatre statistics, the German Theatre and Orchestra Association also publishes annual statistics of works performed during each season in the German-speaking countries, broken down into opera, operetta, musical, spoken theatre and dance. The works are listed alphabetically with date of première, place of performance, number of performances and attendance. The most frequently performed operas in Germany - albeit under the pandemic conditions of the 2020-21 season - were Mozart's Die Zauberflöte, Bizet's Carmen, Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia and Puccini's Madama Butterfly. The fact that the operas of Giuseppe Verdi – otherwise the most frequently performed opera composer internationally – were not to be found in the top places this season was undoubtedly due to the impossibility of performing large-scale works with many choirs, soloists, and a large orchestra. Baroque, classical and contemporary operas with smaller casts have benefited from this development.

Even after the end of the pandemic, the trend towards less opulently scored works seems to be continuing, albeit in a weaker form. In the 2021-22 season, Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro and Così fan tutte as well as Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia and Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore are among the ten most frequently performed operas behind the "eternal" frontrunner Die Zauberflöte (see Figure 4).

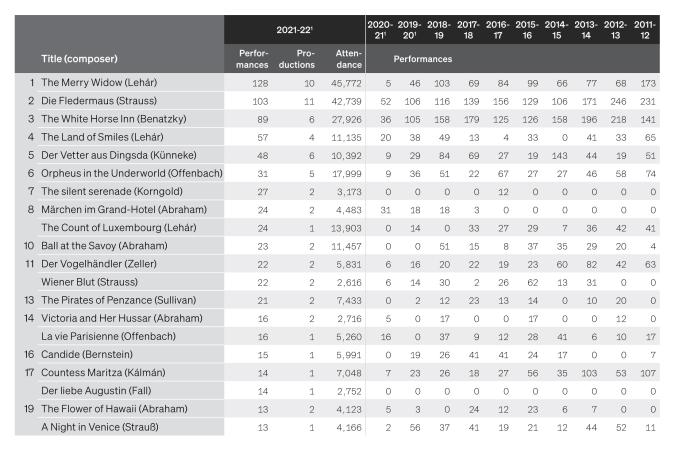

Regardless of the pandemic, the operetta repertoire has recently been far less stable than that of the opera. Although practically no new works have been written for this genre since the Second World War, the increasing interest in ‘excavations’ has recently led to some shifts in the operatic repertoires in German theatres. While in the 2021-22 season, for the first time in many years, it was no longer Die Fledermaus by Johann Strauss but Die lustige Witwe by Franz Lehár that topped the hit list, Paul Abraham and Jacques Offenbach are also represented in the top places alongside Strauss and Lehár with several works each (see Figure 5). At the same time, other works that were rarely performed in the past also found their way back into the repertoire. The work of director Barrie Kosky at the Komische Oper Berlin, who since 2013 has regularly staged highly acclaimed new productions of operettas that had fallen into obscurity, has been a major driving force behind this development.

The musicals repertoire is subject to even greater fluctuations, due in part to the large number of newly composed and/or produced pieces. Moreover, cost and capacity considerations have led more and more municipal theatres to stage musicals and to stand out from their competitors by mounting rediscoveries. The work statistics for 2020-21 and 2021-22 are not very meaningful, not only because of the pandemic, but also because data from most of the large private theatres is not yet available for these seasons. For a long time, the musicals of Andrew Lloyd Webber ruled supreme in their market, but in recent years great successes have been achieved by composers who are in fact stars from the world of pop music: Elton John (The Lion King), Phil Collins (Tarzan) and Udo Lindenberg (Hinterm Horizont), while older pop musicals by Tom Waits (The Black Rider) and The Bee Gees (Saturday Night Fever) experienced revivals. The composer Martin Lingnau achieved rousing success in Germany with four musicals – Das Wunder von Bern, Heisse Ecke, Die Königs vom Kiez – and Die Königs schenken nach.

The business of musicals is driven entirely by popularity and commercial success. German productions of musicals – beginning in the 1980s with Lloyd Webber’s Cats in Hamburg – tend to be staged in private and non-subsidised theatres with no permanent orchestras or ensembles, following in the footsteps of the world’s most important centres, New York’s Broadway and London’s West End. The German musical market seemed saturated at the end of the 1990s after a long-lasting boom. Market consolidation and mergers by the big promoters followed, while unprofitable theatres were closed. A run of seven years was considered standard for a successful show in the mid-1990s, but since then there has been a trend towards shorter runs and more frequent production changes. By and large the German musicals market continues to experience a boom and unbroken demand. Hamburg is Germany’s leading venue in attendance, ranking second in the European musicals’ environment after London. Besides commercial theatres, German theatres with public funding are also mounting classics from the standard repertoire as well as a few original German musicals. Usually, the statistics are headed by the latest hit musicals from Broadway or the West End, produced commercially and ‘en suite’ and usually mounted at only one German venue.

When comparing categories, it becomes clear that, as far as musicals are concerned, production quantity does not count for very much. In any one season, the most popular musicals in Germany will, in a single production, reach larger audiences than the most frequently performed operas, which appear in dozens of stagings during the same period. But all categories show a trend towards greater diversity in repertoire, which raises hopes for a vibrant continued evolution of the still extraordinary German landscape for music theatre in the 21st century.

Prospects and Challenges

Due to the diversity, density and quality of its offerings, the German music theatre scene is perceived as a leader and benchmark in international comparison. At the same time, the current and near future pandemic, ecological and global political crises as well as demographic change pose significant challenges that will point the way for the German opera landscape. The experiences of the coronavirus pandemic have proven the resilience and durability of the stage system. Both the ensemble principle and the repertory system, two specific features of the German theatre landscape, have proven their worth in this extraordinary crisis and revealed their future viability. At the same time, new paths have been taken under the special conditions of the pandemic, which are also likely to be formative for future developments. While planning the repertoire, the company was forced to offer works with smaller casts, which particularly benefited the performance of contemporary and experimental operas as well as baroque works. This has contributed to a further diversification of the repertoire and, above all, strengthened those segments of the programme that will also become more attractive in the future from a climate, cost and sustainability perspective. At the same time, digital offerings and the strengthening of theatre education activities have created important prerequisites for tapping into new visitor potential that has not yet been part of the theatres' regular audience.

In the medium and long term, there is a need for extensive structural renovations and repairs at numerous German theatre locations to maintain the theatres' ability to offer performances. The financial scope of most theatres has been significantly reduced because of the considerable increases in energy and operating costs. From a climate and sustainability perspective, many theatres are also striving to optimise their production methods, implement energy-saving measures and become climate-neutral. Theatres such as the Musiktheater im Revier in Gelsenkirchen, the Deutsches Nationaltheater Weimar and the Theater Regensburg have proactively set sustainability goals and realigned themselves in terms of operational ecology based on corresponding rules of conduct. They receive support from external experts, such as the sustainability experts from the Öko-Institut e.V. or the Deutsche Theatertechnische Gesellschaft (DTHG), which offers practical assistance in the form of information, exchange and further training. In addition, more and more music theatres such as the Oper Leipzig and the Deutsche Oper Berlin are participating in interdisciplinary networks such as the Sustainability Action Alliance. The topic of accessibility has also gained more attention in the music theatre scene in Germany in recent years. Offers for people with impaired vision, such as the live audio descriptions provided by the Staatstheater Braunschweig and the Deutsche Oper Berlin for selected performances, have been well received; ‘tactile tours’ also give participants the opportunity to get a sensory idea of the external conditions – stage design, costumes or props – of the production in advance by touching them or using other forms of haptic perception.

At the same time, however, the competition with film and digital media has led to new technical demands being placed on theatres time and again. Significant developments have taken place in recent decades, particularly in the areas of stage machinery, video and lighting technology and sound engineering. More recently, this has also included impressions from the immersive world of virtual and augmented reality (VR or AR) – so far only sporadically and often in experimental contexts. The production of Christoph Willibald Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice at the Staatstheater Augsburg, which was shown in 2020 and later revived, is particularly artistically successful, transporting its audience into a purely virtual underworld via VR headset. AR has also arrived at one of the world's most prominent opera centres in Germany, the Bayreuth Festival, with Jay Scheib's production of Parsifal, which was staged 2023. At the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf and Duisburg, on the other hand, AR glasses have so far been used less as part of the artistic production and serve more as ‘digital opera glasses’ that provide information and extras as well as performance-synchronised insights into the orchestra pit. The new possibilities create high expectations among audiences, the fulfilment of which is associated with enormous effort and high costs. The current refurbishment projects of large opera houses such as those in Cologne, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt and Stuttgart require investments on a financial scale that is almost unattainable. Small and medium-sized music theatre locations, which will be confronted with similar construction needs in the future, should prepare for possible scenarios and the associated public discussions at an early stage. Communicating the importance of theatre as a public space and a task for society will play a key role, which can only succeed if the representation of a cross-section of society in the audience is guaranteed. Many theatres have been able to significantly increase their reach through digital offerings. The general availability of excellent video productions of opera performances should also increase interest in the live experience among less theatre-savvy sections of the population. Especially during the coronavirus pandemic, larger, technically well-equipped theatres were able to make performances, that could not be shown in front of an audience due to lockdown, accessible to many people via live stream. Smaller digital formats such as the Nuremberg State Theatre's ‘Digital Prop Room’ also offered a low-threshold opportunity to engage with music theatre during the coronavirus pandemic. A more inclusive repertoire and the expansion of theatre education work will also help to make theatres fit for the future. The prospects of the German music theatre landscape will continue to be shaped by tradition, innovation and diversity.

Footnotes

Deutscher Bühnenverein [German Theatre and Orchestra Association], ed., Theaterstatistik 2021/2022: Die wichtigsten Wirtschaftsdaten der Theater, Orchester und Festspiele (Cologne, 2023).

All figures are taken from the Operabase platform, which has covered the international opera scene since 1996. According to its own self-description, Operabase can draw on more than 765,000 performances from around 2,800 cultural institutions in its database. See the statistics online at http://operabase.com/top.cgi?id=none&lang=de&splash=t (accessed 15. November 2023).

Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office], ed., Kulturfinanzbericht 2022 (Wiesbaden, 2022), p. 34.

See James Heilbrun and Charles M. Gray, The Economics of Arts and Culture (Cambridge, 2001).

See the statistics at ‘Revenues of publicly financed theatres (spoken and music theatre)’ (accessed: 15 November 2023).

Deutscher Bühnenverein, Theaterstatistik 2021/2022 (see note 1).

See also Gerald Mertens’s essay ‘Orchestras, Radio Ensembles and Opera Choruses’ online at: https://miz.org/en/articles/orchestras-radio-ensembles-and-opera-choruses

See Deutscher Bühnenverein [German Theatre and Orchestra Association], ed., 2021/22– Wer spielte was? Werkstatistik (Cologne, 2023).