Historically evolved diversity

The current diversity and density of the orchestral landscape in Germany [1] can be traced back to the numerous small states, principalities and free cities that formed their own ensembles and orchestras early on. The oldest German orchestra is that of today’s Hessian State Theatre in Kassel. It was founded by Landgrave William II in 1502 who he hired a certain Henschel Deythinger as a trumpeter in Kassel’s musical retinue. Deythinger and another eight wind players joined forces with the Kassel court chapel to form one of the earliest independent instrumental ensembles under a single director, thereby laying the cornerstone for the emergence of the ‘orchestra’ [2] as a cultural institution. The initial roots of German and European orchestra culture date back even further, to the 15th century. [3] Storied traditional orchestras, such as the Bayerisches Staatsorchester, the Dresden Staatskapelle, the Weimar Staatskapelle or the Mecklenburg Staatskapelle in Schwerin, were founded in the 16th century; still others were assembled at various German courts in the 17th and 18th centuries. These court and church ensembles were in turn followed in the 19th and 20th centuries by the emergence of a bourgeois orchestra culture. Beginning in the 1920s, and again after World War II, they were joined by radio ensembles and other municipal and state orchestras in both East and West Germany. [4] The professional orchestral landscape is further enriched by numerous orchestras and ensembles from the independent scene, which have been founded by musicians themselves, especially since the 1970s, and which are generally not institutionally funded by the public sector and other institutions, but usually only on a pro rata and project-related basis. [5]

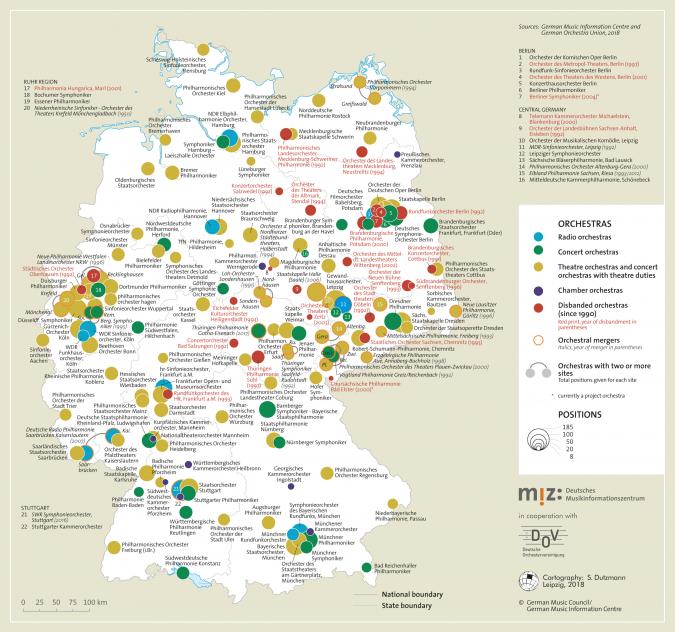

Overview

Germany’s publicly financed orchestra landscape currently consists of 129 professional ensembles. It is basically a four-tier system. The first tier is made up of the 81 theatre orchestras that play primarily in the operas, operettas and musicals mounted at Germany’s municipal and state theatres. Here the spectrum ranges from the great, internationally renowned opera houses in Berlin, Hamburg, Stuttgart and Munich to the small theatres in Luneburg, Annaberg-Buchholz and Hildesheim. Among them are ensembles that function as ‘concert orchestras with theatrical duties,’ though the latter tend to predominate. The second tier consists of 29 concert orchestras (including one civic wind band) that perform largely or exclusively in concert halls. The uncontested leader here is the Berlin Philharmonic, followed by a host of other internationally acclaimed orchestras, among which are the Munich Philharmonic, the Bamberg Symphony, the Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, to name only some of the largest of their rank. The third tier is made up of eight publicly funded chamber orchestras that generally work all year round as string ensembles without their own woodwind or brass sections. Examples include the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, the Württemberg Chamber Orchestra in Heilbronn and the Munich Chamber Orchestra. Finally, the fourth tier consists of 11 radio orchestras, four big bands and seven radio choruses belonging to the ‘Association of Public Broadcasting Corporations in the Federal Republic of Germany’ (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, or ARD), and Radio Orchestras and Choruses Ltd (Rundfunkorchester und -Chöre GmbH, or ROC), in Berlin.

From the 1920s onwards, all the aforementioned concert, radio and theatre orchestras were linguistically referred to as ‘cultural orchestras’, as they played ‘predominantly serious music’ - according to the definition, which was particularly ideologically coloured by National Socialism. This differentiated them from entertainment, revue, operetta and other types of orchestras. [6] In the regional collective agreement, which applies to around one hundred local and state orchestras, the term ‘cultural orchestra’ was only officially replaced in 2019 by the new ‘Tarifvertrag für Musiker in Konzert- und Theaterorchestern’ (TVK) (see below). The defining criteria for professional orchestras are that they are all, for the most part, publicly financed (from tax revenues or broadcast licensing fees), work the whole year round with a permanent membership and generally avoid playing light music or marches.

Mention should also be made of other professional orchestras and chamber ensembles that work either with a regular group of freelance musicians (usually as a private partnership or limited-liability company) or, if they have greater public funding, with permanently employed members. Among them are the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Concerto Köln, the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, the Kammerakademie Potsdam and the Bavarian Chamber Orchestra Bad Brückenau as well as (project) orchestras that thrive on little or no public funding, such as the Deutsche Philharmonie Merck, the Würth Philharmonic (founded in 2017) and the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich. Further information on this subject can be found inRichard Lorber and Tobias Schick’s essay on ‘Independent Ensembles’

Professional orchestras can also be found in the realms of law enforcement, the federal police and the armed forces. However, most of them are wind orchestras or big bands. A few ad hoc orchestral formations play in commercial musical theatres for the duration of a production, mainly in Hamburg, Berlin and Stuttgart. Finally, the number of ‘spa orchestras’ (Kurorchester), an important stepping stone for music students and young professionals until well into the 1970s, has shrunk to a negligible quantity. Owing to a shortage of funds, many health resorts now retain small orchestras, usually from Eastern Europe, but only for a single season.

‘The overall figures show that publicly financed theatres and orchestras are more than just receivers of subsidies. With several hundred highly specialised employees in some cases they are indeed influential players in local economies. They constitute powerful forces of supply and demand at the regional level.’

Collective agreements, pay brackets and orchestra size

The working conditions and salaries of musicians employed in Germany’s publicly financed orchestras are governed by a collective agreement known as the ‘Tarifvertrag für Musiker in Konzert- und Theaterorchestern’ (TVK). It applies across the board for most theatre orchestras and some concert orchestras. This blanket salary agreement for orchestras is the only one of its kind in the world. The TVK dates back to 1971 and was most recently re-ratified in 2019. As a rule, radio ensembles are subject instead to the special salary provisions of the various public broadcasting corporations.

Theatre orchestras are assigned to pay groups A to D, depending on their membership and their number of positions. Those with no more than 55 positions are assigned to the lowest salary bracket, pay group D. Pay group C applies to orchestras with 56 to 65 positions, group B for 66 or more, and group B/F from 78, where F stands for ‘footnote’, since the bonus paid is indicated in a footnote to the table of salaries. Orchestras with 99 positions or more are placed in pay group A; those between 99 and 129 positions are again eligible for a variable ‘footnote bonus’ (pay group A/F2). For orchestras of 130 positions or more, payment of a footnote bonus is mandatory (pay group A/F1). This is the top salary bracket in the collective agreement. There are thus seven pay groups in all. What determines an ensemble’s classification is not the number of positions actually filled, but the number shown in the budget and staff appointment scheme. For decades the grouping of theatre orchestras according to size rather than artistic accomplishments has been subject to criticism. The putative counterexamples are several chamber orchestras in western Germany, most of which, although no larger than 14 to 21 musicians, nevertheless remunerate their musicians under pay group A. Concert orchestras, i.e. those that exclusively or predominantly perform concerts, are categorised in the aforementioned remuneration groups by a separate collective agreement and/or predominantly have their own in-house collective agreement that regulates their remuneration. Particularly large and renowned theatre orchestras also have in-house collective agreements that regulate remuneration, working hours and compensation for media rights, among other things.

Topping the salary pyramid for Germany’s orchestras is the Berlin Philharmonic, followed by the Bavarian State Orchestra, the Berlin Staatskapelle and the great radio symphony orchestras in Munich, Cologne, Stuttgart and Hamburg. At the second tier, yet usually ranking above pay group A/F1, are such ensembles as the Deutsches Symphonieorchester Berlin, the Munich Philharmonic, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, the Dresden Staatskapelle, the Dresden Philharmonic, the Bamberg Symphony, the Hamburg Philharmonic and the Gürzenich Orchestra in Cologne, as well as further radio symphony orchestras and radio orchestras. The other municipal and state theatre and concert orchestras are spread across the aforementioned TVK pay groups, although occasionally some can be found that remunerate their musicians at levels beneath pay group D.

The pay groups of TVK orchestras can be roughly compared as follows: members of a B-level orchestra receive approximately as much salary as a primary school teacher outside the civil service; those in an A-level orchestra earn roughly the salary of a grammar school teacher; and those in an A/F1-level orchestra achieve approximately the salary of a professor at a tertiary-level school of music. In recent years, however, these relations have shifted to the orchestras’ detriment. Orchestra members are, as a rule, employed on unlimited but terminable contracts, not as civil servants.

Gender ratio

The number of female orchestra members has risen steadily since the 1960s and is continuing to do so. Women already occupy more than half of the orchestra positions in the age group from 25 to 45 (see statistics on insured persons in the VddKO's 2021 annual report). [7] The orchestra survey conducted by the German Music Information Centre in 2021 sheds light on this in detail, showing that women are relatively well represented in professional orchestras overall at 39.6 per cent, but are underrepresented in management positions with a share of 30 per cent. In the highest-paid orchestras (above AF/1), the overall proportion of women is lower at 34.5 per cent. At 21.9 per cent, there are even fewer women in senior positions (see the focus topic ‘Am Pult der Zeit!? Chancengleichheit in Berufsorchestern’). However, measures were taken in German professional orchestras as early as the 1970s to give women fair access to positions in the orchestra. At least in the first rounds of many auditions, playing behind a screen was introduced (see the article ‘Kleider zwischen Fräcken: Frauen im Orchester’ by Kathrin Bellmann).

Women conductors remain an absolute rarity, especially as principal conductors (see the article ‘Frauen am Dirigierpult’ by Anke Steinbeck. This situation will change slowly at best, unless more targeted personnel development is organised by the orchestras' legal entities. At German music academies, the proportion of female students studying conducting is already over 36 per cent. [8]

While gender ratio is regularly examined, quantitative analyses of other aspects of diversity have yet to be conducted. The Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz has published a qualitative case study on the experiences of orchestral musicians with a history of origin from Turkey and the Middle East in and around German professional orchestras. [9]

Structural changes: dissolutions, mergers, new legal forms

End of structural change after German reunification

After German reunification, the theatre and orchestra landscape underwent a major structural change, which entailed that several theatres and orchestras - primarily in the eastern German states - were merged with one another, scaled back or eliminated entirely for financial reasons. In the case of orchestras, this fate was met by larger orchestras in erstwhile district capitals (including Schwerin, Erfurt, Potsdam and Suhl) as well as individual radio orchestras of the former East German broadcasting network in Berlin and Leipzig. The map of orchestra sites (see Fig. 1) shows what the orchestra landscape looked like in 1990 after German reunification, and how it has changed since then, primarily owing to mergers and dissolutions.

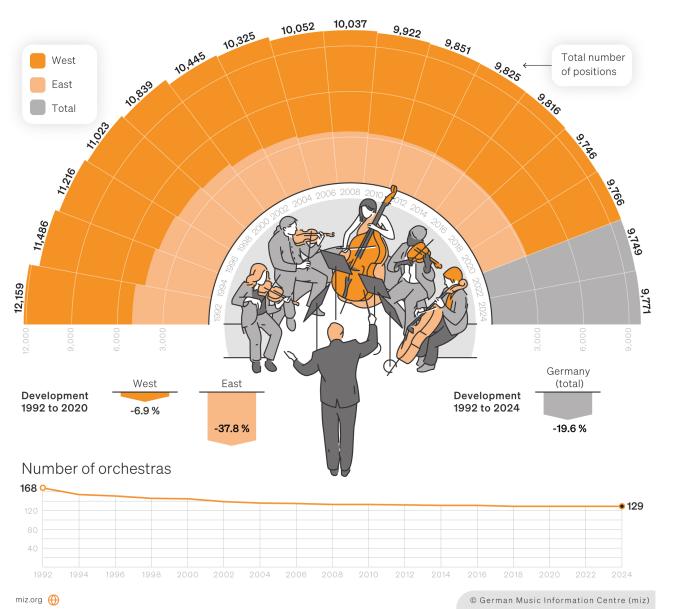

Parallel to this special development in the eastern German states and in former East-Berlin, however, there were also severe structural adjustments in the states of what had been West Germany, primarily in North Rhine-Westphalia. They began with the closing of the Oberhausen Music Theatre in 1992 and continued with the insolvency of the Philharmonia Hungarica (Marl) in 2001. Another case was the liquidation and insolvency of the Berlin Symphony Orchestra in 2004, which now works only on a project-by-project basis. The first all-German stocktaking in 1992 identified 168 publicly financed concert, theatre, chamber and radio orchestras; since then, 39 have been disbanded or merged.

Between 1992 and 2024 the number of registered positions for musicians has dropped from 12,159 to 9,771, a loss of roughly 2,400 positions or 20 per cent. (see Fig. 2). Since then, a few newly created positions in isolated orchestras in the western states have even led to a slight upturn in the number of positions. 30 years after reunification, a fundamental consolidation of the orchestra and staffing situation can be observed.

Changes in legal status

The upheavals of the 1990s were accompanied by the search for locally suitable legal forms for orchestras and theatres, again focusing on the eastern states. In some cases, this led to the creation of publicly financed joint administrative bodies, such as the Thuringian State Theatre of Eisenach-Rudolstadt-Saalfeld (since dissolved) or the Northern Harz City League Theatre in Halberstadt (Saxony-Anhalt), or to registered associations, as witness the Thuringian Philharmonic in Gotha and Zeitz Theatre. Most of all, however, it led to the formation of limited-liability companies. Since 1990 there have been 44 newly founded limited-liability companies for publicly financed orchestras throughout Germany, or existing orchestras have been transformed into such companies. Once again, most are located in the eastern states. [10] This development reached a climax in the mid-1990s. However, these privatisations and expulsions of orchestras from the public coffers were unable to offset the general rise in costs for staff and materials. This is another reason why the wave of privatisation ebbed away after around 20 years.

In contrast, since 1990 there have also been 13 newly founded owner-operated enterprises in which the orchestra’s operations remain legally within the direct reach of the public sector but enjoy greater economic independence and leeway. The prime example of this legal form is the Leipzig Gewandhaus and its orchestra. Registered associations under private law were not always long-lived and frequently led to the founding of limited-liability companies. One problem seems to be that the legal form of the registered association does not provide appropriate tools for the running of orchestras, with their often multi-million-euro budgets and their mixed memberships of natural persons and legal entities (usually municipalities). In particular, the voluntary board members often face considerable legal, financial and liability questions that sometimes find them out of their depth. The insolvencies of the sponsoring organisations in Marl (2001), Zeitz (2003) and the Berlin Symphony Orchestra (2004) offer instances of this. The first transformation of a municipal theatre into a public-law institution took place in Kiel in 2007. In 2023, the Free State of Bavaria decided to upgrade the municipal theatre in Regensburg to a state theatre and to take over up to 50 per cent of the subsidy, but to continue operations in the previous legal form.

Foundations

Since the early 2000s a different legal form has been chosen with ever-greater frequency as a supporting institution for the running of theatres and orchestras: a foundation. An example can be found in Meiningen, where the theatre and orchestra foundation (under private law) also encompasses the former ducal museums. Other examples are the Württemberg Philharmonic in Reutlingen and, since 2002, the Berlin Philharmonic, the latter as a foundation under public law. Since 2004 Berlin’s three opera houses (Deutsche Oper, State Opera Unter den Linden and Komische Oper) have been maintained as the ‘Opera in Berlin’ Foundation (Stiftung Oper in Berlin). Other foundations were newly established for the Brandenburg State Theatre in Cottbus (2004), the Nuremberg State Theatre (2004), the Bamberg Symphony (2005), the Württemberg Chamber Orchestra (2012) and the Augsburg Theatre and Philharmonic (2018).

The advantage of the increasingly popular legal form of the foundation under public law is that it generally cannot become insolvent, and must therefore be financed reliably and publicly on a long-term basis. This raises the trust of the employees and enhances the facility’s reputation in the public eye – and in the eyes of (private) donors. However, since the foundations do not have substantial capital of their own (unlike the multi-million foundations of operas and orchestras in America), these institutions, being wholly subsidised, remain dependent on financing from the public sector. As a rule, they benefit from funding agreements of up to five years’ duration, which at present, gives them much greater planning security than is usually the case with other legal and operational forms.

Occasionally private friends and sponsors of an orchestra no longer assume the organisational form of an association, but augment or replace it with a foundation. This is the case, for example, with the Main-Franconian Theatre in Würzburg, the Northwest German Philharmonic in Herford, the South Westphalian Philharmonic in Hilchenbach, the Lower Saxon State Theatre in Hanover, the Heidelberg Theatre and Orchestra and the Eduard von Winterstein Theatre in Annaberg-Buchholz.

Funding and operational Leeway

Germany’s professional orchestras are funded largely from public subsidies (especially from states and municipalities) or from the budget levy for public broadcasting. The federal government has recently strengthened its commitment, whether by extending financial support to the Berlin Philharmonic and the ‘Opera in Berlin’ Foundation (from January 2018) or by launching the nationwide programme ‘Excellence in Germany’s Orchestra Landscape’ (Exzellente Orchesterlandschaft Deutschland), from which more than 30 orchestras based in all corners of the country have received subsidies for special projects since 2017. Box office proceeds and other earned income differ markedly between genres (music theatre, concert etc.) and between regions. On long-term average, they cover approximately 18 per cent of the budget, often less, but sometimes more. Earnings cannot simply be increased at the drop of a hat: limited seating and space, smaller catchment areas, usually affordable ticket prices and the population’s historically conditioned expectation of state cultural subsidisation leave little room for sustainable short-term boosts of income or sharp increases in admission fees. On the other hand, dynamic pricing offers the potential to increase sales for events that are in particularly high demand.

Further, compared to other countries such as the United States, legal strictures on competition and privacy policies prevent sponsoring organisations of theatres and orchestras from undertaking more extensive direct marketing activities. Germany’s orchestras have fewer administrative staff, which hampers the urgently needed additional PR, communication, marketing and outreach efforts to reach new, differentiated and more diverse target groups. This also applies to the use of social media and digital communication formats. As a rule of thumb, a German concert orchestra (without a concert hall of its own) has around 10 per cent of its artistic employees working in management and administration. In other words, for every 100 orchestra members there are roughly ten administrative employees, and sometimes not even that. In contrast, North American orchestras generally have more administrative personnel, both fulltime and part-time, than artistic staff. Lacking suitable direct public funding, they put far greater effort into fundraising, sponsoring and marketing. However, as private donors and companies enjoy generous tax privileges, the financing of culture in the United States is also basically public, albeit indirectly.

Just how sensitive non-public cultural financing in the United States can be was demonstrated by the impact of the global financial crisis in 2008-09, when the assets and earnings of North America’s orchestras and opera houses plunged, sometimes dramatically. The consequences for these institutions were severe, with cutbacks in staff, programming, projects and salaries, up to and including insolvencies (although the American term ‘bankruptcy’ does not automatically imply shutting down operations, but usually a special form of debt relief and restructuring with continued operations). The global coronavirus pandemic also led to severe cutbacks at individual US orchestras in 2020: The orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera (MET) in New York was completely disbanded for a time. In Germany, no orchestra's existence was threatened during this time, but in around 100 orchestras the employees were sent on short-time working at some point.

Until now, voluntary civil engagement in the broad-based organisation of professional orchestras is only being established in a few cases, for example in the visitor service of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra or the Konzerthaus Berlin. Some institutions take advantage of the opportunities offered by a ‘Voluntary Social Year’ in culture in the areas of music education, community music and orchestra management.

Donors’ associations and friends’ schemes exist and are also important, for they expand the basis for regional appreciation and awareness of culture. But like sponsorship, they do not play a truly significant role in the financing of orchestras. At present, Germany’s tax laws offer only small incentives to expand income from sponsorships, donations and patronage, which in any case have only served to support isolated projects or events.

Events and attendance, box office proceeds and overall budgets

Despite the structural transformation described above, the current statistics from the German Theatre and Orchestra Association (Deutscher Bühnenverein) show constant growth in the number of concerts, from around 6,900 in the 2000-01 season to 9,200 before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic (see Fig. 3). However, these figures only partly include events and attendance for radio orchestras and radio symphony orchestras. The number of concertgoers increased proportionately, exceeding the four-million mark for the first time in the 2006-07 season. The predominantly positive seasonal balances, high-capacity utilisation figures and pleasing annual reports of many music theatres, concert halls and orchestras in recent years since around 2015 now point to a general positive trend among music audiences.

The temporary restrictions on theatre operations during the coronavirus pandemic between March 2020 and spring 2022 naturally led to a massive drop in audience capacity utilisation. Orchestras and theatres that suspended their subscriptions during the pandemic had greater problems winning back their regular audiences than those that maintained a limited offering. This is one of the findings of a nationwide trend survey conducted in December 2022/ January 2023, in which 122 out of 129 orchestras took part. [11]

The German Orchestra Association (since October 2022: unisono Deutsche Musik- und Orchestervereinigung) listed about 15,000 concert events for the 2017/18 season for all orchestras and radio ensembles (including radio choirs and big bands) (last full survey before the coronavirus pandemic), including 6,025 symphony and choral concerts (including trips abroad). For the first time since concert statistics have been compiled, the number of music education events (concerts for children and young adults, concerts of school pupils and workshops held in schools) totalled 6,325, exceeding the number of regular symphony and choral concert events. This development (see Fig. 4) underlines the particular importance now attained by the orchestras’ steadily growing outreach activities, i.e. workshops, concerts for children and young adults, and concerts for schoolchildren. Unfortunately, it was not possible to compile precise figures for the numbers of concertgoers involved since this information is not always recorded for school or open-air events or for guest performances.

The crowds who throng to the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, the Ruhr Music Forum in Bochum, the reopened Kulturpalast in Dresden and other new or renovated venues since around 2015 could be interpreted as a sign of a turnaround in the attractiveness of classical music events. The problems lie in precisely capturing, breaking down and incorporating attendance figures from concert halls (e.g. those in Dortmund, Essen and Hamburg) and from the major German music festivals (Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, Rheingau), which feature German and foreign orchestras and many other ensembles but fail to keep reliable attendance records.

According to figures from the German Theatre and Orchestra Association, attendance and capacity utilisation at music theatre events and concerts by theatre orchestras (excluding concert orchestras) have not changed significantly between the 2000-01 and 2016-17 seasons. They have remained relatively high, with average capacity utilisation between 70 and 80 per cent. [12] It can be assumed that the decline in visitor numbers between 2020 and 2022 due to the coronavirus pandemic will be fully offset. More and more music theatres and orchestras are attempting to attract and retain new audiences by improving their subscription methods and programme offerings. Their success was evident in the past: the Düsseldorf Tonhalle, for example, more than doubled its number of subscribers to over 4,900 between 2014 and 2018. Similarly, before the pandemic, many opera houses and concert halls have reported record attendance, raising the question of whether, and to what extent, the ‘audience extinction’ predicted for decades is likely to happen (see also Karl-Heinz Reuband’s essay on ‘Preferences and Publics’).

The overall figures show that publicly financed theatres and orchestras are more than just receivers of subsidies. With several hundred highly specialised employees in some cases they are indeed influential players in local economies. They constitute powerful forces of supply and demand at the regional level, creating bonds with highly skilled employees through their methods of production. This in turn leads to backflow in tax revenue and allows local business branches to profit directly or indirectly from the theatres’ and orchestras’ activities.

The state of Germany’s opera and radio choruses and radio ensembles

The establishment and constant change of public broadcasting structures after the Second World War and the reorganisation of the GDR and West Berlin broadcasting were accompanied by serious structural adjustments for the respective radio ensembles. The last time the number of radio symphony orchestras declined was in September 2016 following the merger of the SWR orchestras from Freiburg/Baden-Baden and Stuttgart to form the SWR Symphony Orchestra in Stuttgart. The radio ensembles continue to be a mainstay of high-quality music production, professional music education, ambitious programme policy and the promotion of contemporary music in Germany. They are thus an integral part of the cultural and educational mandate laid down in the Interstate Broadcasting Agreement (Rundfunkstaatsvertrag).

At present, the public broadcasting corporations are operating the following music ensembles: The Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR), a ‘four-state broadcaster’ (Vier-Länder-Anstalt), maintains the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester, the NDR Bigband and the NDR Vokalensemble in Hamburg and the NDR Radiophilharmonie in Hanover. The Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) operates the large symphony orchestra, the smaller Funkhausorchester, the WDR Rundfunkchor and the WDR Bigband in Cologne. The Hessischer Rundfunk (hr) also originally had four orchestras at its Frankfurt/Main location. Today, the hr Symphony Orchestra and the hr Big Band still exist. The Südwestdeutscher Rundfunk (SWR) is responsible for the SWR Symphony Orchestra and the Vokalensemble in Stuttgart. The SWR Bigband (which emerged from the Erwin-Lehn Südfunk Tanzorchester) is as a limited-liability company not directly supported by the SWR. The Deutsche Radio-Philharmonie Saarbrücken-Kaiserslautern is operated as a joint organisation of the SWR and the Saarländischer Rundfunk (SR) following the merger in 2007. In Munich, the Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR) operates the large BR Symphony Orchestra, the smaller Munich Radio Orchestra and the BR Choir. The Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) still has the MDR Symphony Orchestra and the MDR Choir from the original five orchestras of the Sender Leipzig (1990). The MDR also supports the MDR Children's Choir, which was founded in 1948 and systematically introduces children from the age of three to choral singing.

A special case is the Rundfunk Orchester und Chöre gGmbH (ROC) Berlin, which was formed after 1990 through the expansion of the West Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (RSO) GmbH. The shareholders are the Federal Republic of Germany (35 per cent), the State of Berlin (20 per cent), the Deutschlandradio (40 per cent) and the RBB (5 per cent). The ROC is responsible for the Deutsches Symphonieorchester Berlin (formerly RSO), the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, the Rundfunkchor Berlin and the RIAS Kammerchor. The RIAS Bigband was dissolved by the ROC in 2009.

The political, social and sometimes populist debate about the mandate, equipment, programme offerings and adequate funding of public service broadcasting does not stop at questioning the expenditure and existence of the radio ensembles. In all of this, it should not be forgotten that, taken together, the musical ensembles of the ARD broadcasting network (orchestras, choruses, big bands) cost roughly €180 million each year, which merely amounts to some 41 cents of the monthly licensing fee for private households.

During the coronavirus pandemic, the radio ensembles were among the few music ensembles that continued to broadcast live music and concerts from their broadcasting and concert halls and studios via all possible broadcasting channels on radio, television and live stream, while most other venues, concert halls and theatres were closed.

In addition, the broadcasters with their music ensembles and their event programmes provide a basic cultural service in their respective broadcasting areas: i.e. every year, the WDR Symphony Orchestra goes on a school tour with all the chamber music formations available from its members and reaches 10,000 pupils in numerous local schools throughout North Rhine-Westphalia – especially in regions where there is no municipal orchestra. In addition, the WDR offers year-round music education programmes for preschools, primary schools and secondary schools as well as the multimedia WDR Klangkiste, a music workshop, the WDR Big Band's Play Along app, which was awarded the ‘Innovation 2020’ prize, and the WDR Rundfunkchor's ‘Sing Along’ app.

New orchesral activities – influencing the world of music and the society

It is a well-known fact that concert and theatre orchestras have a wide variety of ways to influence the world of music besides giving concerts of different types and performing operas. In fact, all orchestras have a broad array of chamber-music formations which either exist permanently or convene on an ad hoc basis to enrich the regional concert scene, voluntarily and often quite apart from their official duties. The realms of music schools and amateur, student, and national or state youth orchestras, the National Youth Orchestra (Bundesjugendorchester) not to mention church congregations, profit in many ways from the involvement of orchestra members. Professional musicians are frequently active on a volunteer basis, not just as instrument teachers, but as soloists or expert mentors to these non-professional orchestras. To choose one example, the Berlin Philharmonic has entered a partnership with the National Youth Orchestra that involves musical work at many levels, including coaching for individual vocal groups and mentoring for individual BJO members. More than 50 further partnerships exist between professional and youth orchestras throughout Germany.

There is also a welcome upward trend in orchestra activities for children, young adults, families and schools, as is shown by the figures now regularly collected (see Fig. 4). The Young Ears Network (‘Netzwerk Junge Ohren’), with headquarters in Berlin, was newly established in spring 2007. Here various music associations with more than 1,000 members in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Luxembourg work jointly across national borders to co-ordinate and expand the outreach activities of orchestras, music theatres and concert halls, as well as festivals and other institutions, mainly in the German speaking countries. For several years, the network awarded its internationally acclaimed Young Ears Prize (‘Junge Ohren Preis’) for outstanding musical outreach projects in the German-speaking countries.

Community music is a relatively new field for orchestras and concert halls in Germany. Originating in the UK in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the focus here is not on audience development. Community music is about ‘active music-making in groups, where the music is developed as an expression of this community and reflects its social context.’ [13]

The musical and social processes are on an equal footing. The programme is aimed at all people regardless of origin, religion, education, age, disability, gender, income or previous musical training. Ideally, groups are guided and supported by appropriate specialists, the community musicians. It is primarily about active participation. The first community music departments have existed at the Konzerthaus Dortmund since 2019 and at the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg since the 2022/23 season. Orchestras, music theatres and concert halls that want to be perceived as culturally and socially relevant in a community must constantly review their social connectivity.

Various questions arise in this context, such as: Does the composition of the concert audience reflect only a small section of the population or a broader one? Does the concert programme also include (increasingly more) works by female composers and works that lie outside the European cultural canon?

Another important contribution from orchestras to the social discourse was their extraordinary commitment when faced with the situation of refugees that arrived in Germany from autumn 2014 on. More people than ever from the Middle East were now seeking refuge from war and persecution. In an impressive number of projects and events, orchestras throughout Germany launched music-education projects for refugees in every age group, mounted welcome and benefit concerts and helped in other ways to tackle questions of migration and integration.

In the spring and summer of 2022, concert halls, music festivals and orchestras, including the BJO, continued to collect donations and organised support for the people affected by the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine with a variety of campaigns and concerts

Although the cultural sector consumes very few resources compared to other sectors of the economy and CO2 emissions are therefore manageable, the issue of sustainability is also becoming increasingly important for orchestras and radio ensembles. This also corresponds to the increasingly clearly articulated expectations of cultural policy at federal, state and local level. The first orchestras, opera houses and concert halls have drawn up carbon footprints in order to take suitable measures for more sustainable action. Orchestra members from over 30 German professional orchestras are now involved in the ‘Orchestra of Change’ association. The association sees climate protection and nature conservation as part of its cultural mission. Its members are committed to sustainability and, for example, address the climate crisis in creative concert formats. With regular benefit concerts, the members support the joint main project of the sustainable cultivation of rare wood species in Madagascar for instrument making as well as numerous regional climate and nature conservation projects. There is a corresponding guideline for sustainability in orchestral and concert operations, which was published by unisono. [14]

Prospects for the future

The coronavirus pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the security of energy supplies and increased inflation with rising rents and prices as well as falling purchasing power are leaving their mark on cultural and musical life. However, it seems that audiences are returning to concerts and opera and that the pre-corona level will be reached again. [15] It will be important to build on the successful trends of high-capacity utilisation of events and continue them.

In addition to aspects of ticket demand and capacity utilisation, it remains to be seen at what level the financing of orchestras and theatres, which was largely consolidated by the federal states and local authorities by the beginning of 2020, will develop. High inflation means rising wages and salaries for employees, which the companies will not be able to refinance on their own. One structurally ineradicable problem is that human resources make up roughly 85 per cent of budgets in theatres and orchestras, whereas they account for only some 30 to 45 per cent [16] of the general public budget. Cushioning just 1 per cent of linear annual growth in labour costs, the company's own profitability ratio would have to be increased by around 5 per cent in the long term. However, this seems unrealistic. Orchestra and theatre companies are therefore dependent on regular compensation from their public funding bodies for rising personnel and material costs.

Even after the coronavirus pandemic has subsided, Germany’s publicly financed music theatres and orchestras will continue to face a battle for public resource allocations in the future. The arguments that the administration and politicians have brought forth in the past for the alleged need for further cutbacks have proved untenable. Ultimately, the proportion of cultural funding in public budgets is too small compared to other departments. Since around 2015, cultural policy in many federal states and municipalities has undergone a rethink, focussing more on stable basic funding for cultural institutions and multi-year funding prospects. However, there are still major differences between individual federal states. The coronavirus pandemic itself has led to a change in awareness of the need for better funding for the independent scene and freelance artists.

The successful further development of the German orchestral landscape requires the corresponding political will for sustainable funding. The debates on this are being held at the federal, state and local levels.

Footnotes

See Gerald Mertens, Orchestermanagement ( 2nd ed., Wiesbaden 2018), pp. 5–6. It states: ‘Worldwide, the number of professional orchestras performing year-round, predominantly in classical symphonic formations, is estimated at around 560 to 600. Around a quarter of these – currently 129 – are based in Germany.’

See ibid. p. 6 and Hartmut Broszinski et. al., Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, vol. 5, (Kassel et al., 1996).

The Staatskapelle Weimar was founded in 1491, but did not exist continuously, as it was disbanded several times in its early days. See anon. ‘Geschichte des DNT’ online at https://www.nationaltheater-weimar.de/de/ueber-uns/geschichte.php (accessed 23 June 2023).

See Mertens, Orchestermanagement (see note 1), p. 6.

See ibid. and Tobias Schick’s and Richard Lorber’s essay ‘Independent ensembles’ online at https://miz.org/en/articles/independent-ensembles.

See Martin Rempe, Kunst, Spiel, Arbeit. Musikerleben in Deutschland, 1850 bis 1960 (Göttingen 2020), pp. 246–252.

The data refers to the active insured persons, i.e. the musicians employed by the VddKO member orchestras on the reporting date (compulsorily insured persons), the musicians who work for the member orchestras on a short-term basis and are therefore not compulsorily insured (voluntarily insured persons) and the insured persons who continue their insurance through their own contributions but were no longer employed by the orchestras on the reporting date. The proportion of women exclusively among the compulsorily insured up to the age of 45 is somewhat lower, see statistics ‘Geschlechter- und Altersverteilung in Berufsorchestern’) online at https://miz.org/en/statistics/geschlechter-und-altersverteilung-in-berufsorchestern

See statistics in ‚Studierende in Studiengängen für Musikberufe nach Geschlecht und ausländischer Staatsbürgerschaft‘ online at https://miz.org/en/statistics/studierende-in-studiengangen-fur-musikberufe-nach-geschlecht-und-auslandischer-staatsburgerschaft

See the study by the Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, ed., ‘Wie divers sind Orchester? Qualitative Einzelfallstudie unter Orchestermusiker:innen mit einer Herkunftsgeschichte aus der Türkei sowie dem Nahen und dem Mittleren Osten in und um deutsche Berufsorchester’ (2021).

See ‘Alphabetische Aufstellung der deutschen Berufsorchester mit Einstufung und Planstellen’ in Das Orchester 2 (2022).

See report ‘unisono-Trendbefragung stellt Rückkehr des Publikums fest’ (2023).

See German Theatre and Orchestra Association, ed., Theaterstatistik 2016/17 (Cologne, 2018).

Alicia den Bánffy-Hall, Burkhard Hill, ‘Community Music’ in Kulturelle Bildung Online (2017) online at https://www.kubi-online.de/artikel/community-music-einfuehrung (accessed 22. June 2023). On the subject of community music, see also Alicia de Bánffy-Hall et. al. ‘Community Music’ online at https://miz.org/en/articles/community-music

See unisono ‘Nachhaltigkeit im Orchester- und Konzertbetrieb’ online at https://uni-sono.org/position/nachhaltigkeit-im-orchester-und-konzertbetrieb/ (accessed 23. June 2023). For further information see the article by Stephan Schwarz-Peters ‘Orchester des Wandels: Ein neues Bewusstsein schaffen’ online at https://miz.org/en/articles/orchester-des-wandels-ein-neues-bewusstsein-schaffen

See report ‘unisono-Trendbefragung’.

See Mertens, Orchestermanagement (see note 1), pp.52–58 .