Just how great their magnetism can be is clearly exemplified by the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. Ever since it opened its doors in January 2017 it has been not only a cultural edifice very much in the public eye, but a milestone in Germany’s concert hall land scape. It has rekindled debates on what repertoire a concert hall should offer, how much it should cost and what it stands for, and has transported those debates into public awareness. Similarly the Dortmund Konzerthaus demonstrates just how strong an impact such an institution can have in an urban context. Ever since it opened in 2002 it has developed a visibility far beyond the confines of its region. Its location in downtown Dortmund has helped to raise the value of the Brückstrasse Concert halls are among the great attractions of the cultural landscape. Visible from far and wide, these centres of classical music contribute essentially to a city’s image and set culture in the heart of society. Just how great their magnetism can be is clearly exemplified by the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. Ever since it opened its doors in January 2017 it has been not only a cultural edifice very much in the public eye, but a milestone in Germany’s concert hall land scape. It has rekindled debates on what repertoire a concert hall should offer, how much it should cost and what it stands for, and has transported those debates into public awareness. Similarly the Dortmund Konzerthaus demonstrates just how strong an impact such an institution can have in an urban context. Ever since it opened in 2002 it has developed a visibility far beyond the confines of its region. Its location in downtown Dortmund has helped to raise the value of the Brückstrasse District, one of the city’s most disadvantaged areas until well into the 1990s. The neighbouring city of Bochum celebrated the opening of a newly erected concert hall in autumn 2016: the Anneliese Brost Music Forum Ruhr. Dresden followed suit with its completely modernised Kulturpalast in early 2017. At almost the same time Berlin opened the new Pierre Boulez Hall, a spectacular venue for chamber recitals.

Germany, with its rich and varied musical tradition, has a high density of musical venues. Almost every medium-sized city has at least one hall for musical performances. In many cases the question of which conditions must be satisfied for the appropriate performance of music, especially the orchestral repertoire from the classical period to the modern era, has even led to heated concert hall disputes. Saarbrücken, Stuttgart, Nuremberg and Munich are currently raising the question of what a concert hall should mean for their respective cities: a building where music is performed, where people can meet or where events can be held for purposes of prestige? The discussions surrounding Munich’s concert hall in particular have drawn great attention from the media. Two renowned orchestras, the Bavar ian Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Munich Philharmonic, need a venue for their concerts, and the urgently necessary renovation of the Gasteig Cultural Centre, beginning in 2020, made the cries for a new building louder than ever. In particular the site became a bone of contention between the city’s administrators, inhabitants and art experts. The choice ultimately fell on a former industrial area currently being developed as a new urban district with residential flats, educational facilities, start-ups and service providers. Here the new hall is scheduled for completion by 2021. Like Munich, Nuremberg too, after an architectural competition held in 2017, found a winning design for a new concert hall, scheduled to be built adjacent to Meistersinger Hall beginning in 2021.

‘Many concert halls devise new series of events in order to distinguish themselves from other houses and make their programmes unique.’

Defining features: what is a concert hall?

Philharmonie and Tonhalle, Konzertsaal and Konzerthaus, Kulturzentrum and Musikzentrum: these terms all designate much the same thing, namely, a building constructed primarily for the performance of classical music. [1] But what does a concert hall do in particular, and how do the facilities differ from each other? A number of aspects have to be taken into account, such as the proportion of classical music in the repertoire, the range of genres or the importance of guest performances. Unlike an opera house, which can be described as a performance venue with independent staff and management that mounts its own productions of stage works, the term ‘concert hall’ cannot ultimately be captured in a general definition. Nonetheless, concert halls have defining features of their own. They involve architectural aspects and questions of use, operation and artistic profile. These aspects can all be drawn upon to describe a concert hall and set it apart from other buildings.

Building

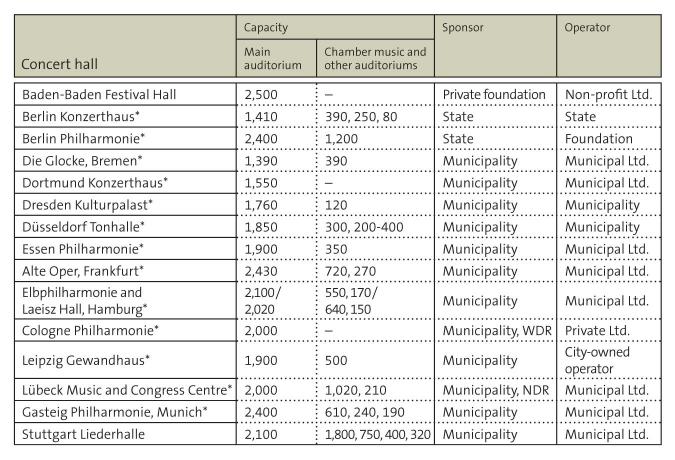

The basic architectural prerequisite for a concert hall is an auditorium filled with seats, suitable both in size and acoustics for the performance of classical music and capable of accommodating several hundred listeners. Most German concert halls also have additional rooms that serve especially for the performance of chamber music and solo pieces. Besides buildings constructed specifically for concert operations, this also includes those originally set aside for other purposes. The Düsseldorf Tonhalle, for example, originated in the 1920s as a planetarium. Not until the late 1970s did it become a new central venue for classical music to succeed the Tonhalle destroyed in World War II.

Use

In addition to architectural features, manner of use is decisive for classifying a building as a concert hall. Here, for the most part, classical music is performed. Nor is its public perception as a concert venue disturbed by wide-ranging, even non-musical offerings, as happens for example in most municipal auditoriums. Certain buildings, however, such as the Stuttgart Liederhalle or Munich’s Gasteig, augment their musical offerings with many other events, especially congresses. Here, as elsewhere, the lines of demarcation are fluid.

Guest performances

Concert halls regularly feature performances by visiting artists. Not only are they available as venues for largely regional orchestras, they also give national and international ensembles opportunities to perform at various points in the year. Some halls have their own ensembles, such as the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra or the Berlin Philharmonic. No fewer than two ensembles have their home in the Cologne Philharmonie: the Gürzenich Orchestra and the West German Radio Symphony Orchestra. And since the 2016-17 season the former North German Radio Symphony Orchestra, now rechristened the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, even bears the name of its new venue. The crucial thing for such concert halls is, however, that the resident ensemble, despite its many special rights and privileges, does not exclusively determine the concert programme.

Artistic profile

Perhaps the most important distinguishing feature of a concert hall, as opposed to other musical venues, is its artistic profile. Ideally, besides being open to the largest possible international circle of artists, it should present and develop the full range of the concert repertoire. This is usually done within an organisational structure headed by an intendant (managing and artistic director) and sporting a distinctive profile in its programming. A concert hall’s alignment also reflects an understanding of its role as a cultural institution: it is expected to offer artistic impulses and project a distinctive identity through intelligent programming, thereby actively shaping the musical life of its particular location. It is no longer enough to present celebrated musicians on stage: rather, what is needed is an effective dramaturgy sustained by every department of the hall and projected to the outside world with self-confident aplomb.

Sites and development

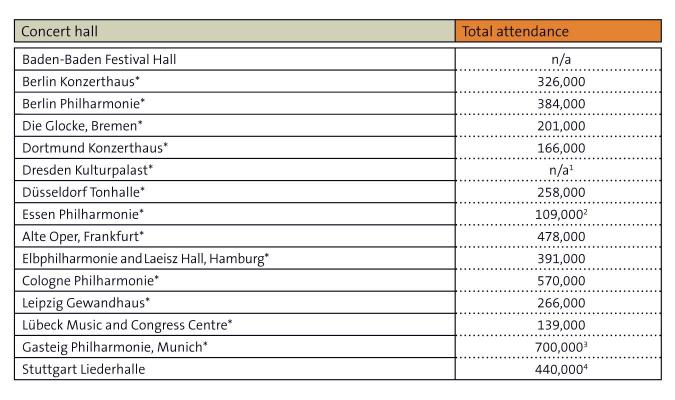

The German Music Information Centre lists 15 institutions in Germany that possess the above-mentioned features of a concert hall. They are spread across the entire country and can be found in the most varied of regions, from the Rhine-Main area (the Alte Oper in Frankfurt) and southern Germany (the Gasteig in Munich, the Stuttgart Liederhalle, Baden-Baden Festival Hall) to Saxony (the Leipzig Gewandhaus, the Dresden Kulturpalast) and northern Germany (Die Glocke in Bremen, Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie and Laeisz Hall, the Lübeck Music and Congress Hall). They are especially numerous in North Rhine-Westphalia, with the Essen Philharmonie, the Dortmund Konzerthaus, the Cologne Philharmonie and the Düsseldorf Tonhalle all located within a radius of roughly 100 kilometres. Berlin, too, is represented by two concert halls: the Philharmonie and the Konzerthaus. All in all, 13 of these concert halls, plus four in Austria, Luxembourg, Switzerland and the Netherlands, have joined forces in the German Concert Hall Conference (Deutsche Konzerthauskonferenz), founded in 2001 with the goal of promoting the conservation, expansion and further development of concert life. In addition to these concert halls, Germany has a number of other halls that often serve as venues for ensembles based in their particular region or locality, and which function along much the same lines as concert halls for guest performances and festivals. Examples include the BASF Feierabendhaus in Ludwigshafen, Nikolai Hall in Potsdam and Rudolf Oetker Hall in Bielefeld, not to mention concert churches such as the Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Concert Hall in Frankfurt an der Oder.

Besides the established concert halls, venues have arisen particularly in recent years to present new concert formats. Performance sites such as Radialsystem V in Berlin’s East Station (Ostbahnhof), originally a private facility but acquired by the State of Berlin in 2018, offer a platform not least to independent ensembles, attracting interested and varied audiences and pursuing goals that differ markedly from those of concert halls.

The evolution of Germany's concert hall landscape

The uniqueness of concert halls, and the social and culture-political demands they entail, are often expressed in their very architecture. Already in the 19th century concert halls became prestigious sites that accommodated the desire of the educated middle-classes for a select cultural space not open to the masses. The crucial standards were set with the construction of Vienna’s Musikvereinssaal (Musical Society Hall) in 1870. The latter half of the 19th century witnessed a veritable building boom of concert halls, both in Europe and the United States. This initial burst of activity was followed by a long hiatus.

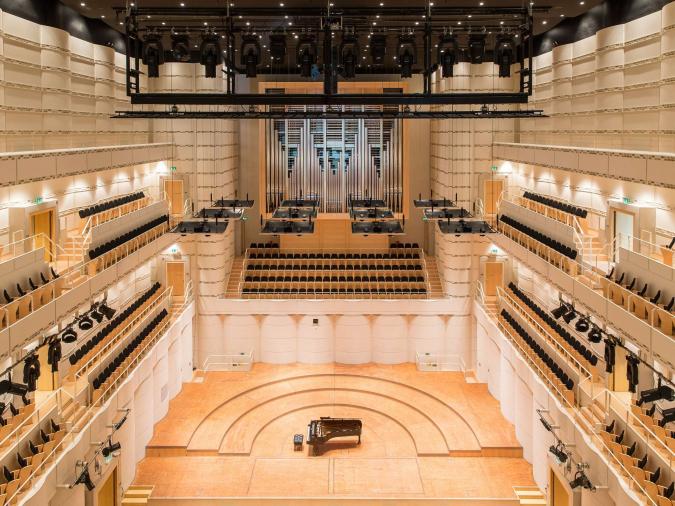

In 1963 the most influential new concert hall of the post-war years opened its doors in Berlin: the Philharmonie. It was a unique achievement whose ‘vineyard’ interior design influenced other concert halls, including the recently built Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. Its architecture, designed by Hans Scharoun, expressed the demands and wishes of its day: classical music was to be reintroduced in a prestigious postwar context, reviving (West) Germany as a cultural and economic powerhouse. This statement was all the more striking in that West Berlin, in the 1960s, was not particularly noteworthy as a cultural capital, unlike Cologne, a leading hub of museums, culture and theatre.

The opening of the Cologne Philharmonie in 1986 was a sensational event. Built underground, this cultural edifice achieved two markedly different goals, offering a well-conceived programme while reflecting the zeitgeist of its inaugural decade – aiming, among other things, to involve the entire community, as symbolised by its architectural unity with the adjoining Ludwig Museum. By deciding in favour of an institution headed by an intendant and featuring its own programme, the Cologne Philharmonie contrasted sharply with the other buildings that arose during the 1970s in answer to Hilmar Hoffmann’s cultural-political catchphrase, ‘Culture for Everyone!’

The demand to make culture (in this case classical music) accessible to as many people as possible found pragmatic expression in multi-purpose cultural buildings. Munich’s Gasteig complex, completed in 1985, with its wide range of offerings and contrasting modes of utilisation, was virtually paradigmatic in this respect. Other examples include the Stuttgart Liederhalle (opened in 1956, en larged into a cultural and congress centre in 1991) and Lübeck’s Music and Congress Hall (opened in 1994).

The Cologne Philharmonie, with its unusual conception and programmes, drew acclaim from all over the world. For the first time since the two world wars, it revived the concert hall idea epitomised by the Vienna Musikverein, generating a pro gramme immediately recognisable as a ‘signature’. It served as the point of departure for other modern concert halls.

Mode of operation, organisational structure and funding

Despite the trend-setting role of the Cologne Philharmonie’s intendant-led model, Germany’s concert halls do not have a consistent operational model. Rather, three such models have emerged since 1850:

- Following the model of Vienna Musikverein, the hall’s operations and event management are entrusted to a non-profit and usually private organisation. Baden-Baden Festival Hall, for example, is run by a non-profit company, whereas the Cologne Philharmonie is headed by a private limited-liability company.

- Another group of concert halls is closely associated with particular ensembles. In these cases a building was constructed for a specific orchestra or originated at the same time that the orchestra was founded, often reflected in the congruity of their names. Examples include the Leipzig Gewandhaus, the Berlin Philharmonie, the Düsseldorf Tonhalle and the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. Whether the house and the orchestra share a common administration (as in Leipzig and Berlin) or soon went their separate ways (as in Amsterdam), the orchestras have continued to govern the programming of the house con cerned. For example, 80 per cent of the concerts in Leipzig are given by the Gewandhaus Orchestra, and the Berlin Philharmonic is what might be called the ‘flagship ensemble’ of the Philharmonie.

- Finally, new concert halls were built by public authorities and financed by private donations. One example is Laeisz Hall in Hamburg, which is basically available to all of the city’s orchestras, choruses, chamber music societies and event organisers for their own use. Further examples of such rental operations are Munich’s Gasteig and Die Glocke in Bremen.

However, there also exist variants of these three models. Not all of Germany’s concert halls can be assigned unambiguously to a single model; some have distinctive features that ultimately lead to hybrids of these three types.

The various operational models (see Fig. 1) have a considerable influence on the house’s programming and overall organisational structure. It is crucial whether a house is run by a managing director (MD), generally with little impact on its artistic alignment, or whether an orchestra serves as final arbiter in decisions affecting the entire house, or whether the artistic and business direction is exercised by an intendant who also functions as MD of the limited liability company, as in the Cologne Philharmonie. The Munich Gasteig, in turn, is operated by a managing director who has little impact on the house’s repertoire but must keep his or her eyes on economic matters, being responsible for them, while keeping an eye on concert expenses in close cooperation with the general music director.

Internal organisation and staff

Close cooperation between the departments of a concert hall is of im mense importance, not only for its managerial level. Employees with professional experience in management, marketing, business administration and technical equipment must work together to ensure the success of a concert. The artistic management office, which coordinates the scheduling and organisation of the artists’ transportation and lodging, must be in constant contact with the technical department in order to arrange the rehearsal schedules. The press room, perhaps wishing to conduct an interview with an artist for the hall’s publication series, must like wise speak with both departments. The intendant may want to welcome the artists and must therefore know their time of arrival. While the technical department monitors the building’s systems and facilities, ensuring that concerts take place without a technical hitch, the building manager takes care of coordinating the employees in the foyer and everything that must be arranged before and after the concert. This includes ushering the audience, with whom the box office must also be in close contact.

In these days of social networks and the instantaneous transmission of positive or negative experiences, contact with the audience is becoming increasingly important. Successful communications, whether internal or external, are indispensible for an up-to-date concert hall that wishes to economise, regardless of how its inhouse departments and operations are structured.

Financing

Differences can also be noted in the way concert halls are financed. Some houses receive financial support from municipal authorities; others must rely on various forms of patronage and intensive fundraising and marketing campaigns. But even houses that receive public funding must face the task of abandoning the public sector as their sole source of funds and earning some of the costs of their concerts themselves.

Among the possible models of non-public financing are fundraising and sponsorship, which necessarily entail entering into conversations with potential donors and establishing mutually beneficial business relations. The indispensible tools of a concert hall’s fundraising departments include committed networking, fundraising, cooperation with local or regional companies and direct acquisition. Baden-Baden Festival Hall, for example, receives no money from the public sector; true, the building belongs to the city and state, but a private foundation created an operating company that finances the house through ticket sales and donations. Die Glocke in Bremen, for its part, earns a considerable proportion of its budget by renting spaces to third parties. The roughly 300 events it offers every year are coordinated by its operator and landlord, Glocke Veranstaltungs-GmbH. Finally, the Leipzig Gewandhaus augments its municipal subsidies via a circle of friends and the Sponsors Club, which generates additional income through its members. [2]

Programming

Regardless of how a concert hall is organised and structured, its programming is of central importance. Concert halls differ not only in their presentation of events but equally in the way they stand out with their ‘stylistic cocktail’. One key factor in programming is the proportion of guest events, which can vary between 40 and over 80 per cent from one house to another. Here the internationalisation of music is a major factor. Orchestras and soloists are usually booked out years in advance and know where they will be on stage, with which programme under which conductor, in three or even five years’ time. This turns programming into a balancing act between thematic emphases and availability. An intendant develops the season’s programme in close consultation with agencies and artistic management companies. This creates competition not only among concert organisers on the national level, but among concert halls throughout the world. In this way the influence and special importance of operations led by an intendant become obvious: the bundling of all events, whether conceived by an external concert organiser or a brainchild of the house’s own programming policy, must suit the house’s overall philosophy and be communicated as such. The audience should recognise the house’s signature and perceive it as autonomous.

The range of offerings in concert halls extends from early music and the classicalromantic repertoire to contemporary or little-known works. Orchestral works appear alongside chamber music and solo recitals with various instruments or vocal types. There may also be complementary events such as cabaret acts, floor shows and happenings. All in all, however, the greatest proportion in most houses falls on classical concerts.

Besides guest performances, a feature shared by all concert halls to various degrees and in various forms, another essential aspect that defines a concert hall is year-round activity. Events are offered throughout the entire year, so that the preparation of a season’s concert dates never comes to an end. Also worth mentioning in this connection is a trend in several houses toward quality enhancement and image building. Even smaller concert halls are at pains to invite world-class performers, thereby sharpening their artistic profile both nationally and internationally. Performers of high artistic calibre, and the resultant high quality of the works performed, are no longer the exclusive domain of the great traditional houses. Especially over the last 25 years there has been a growing specialisation in such areas as contemporary and early music, i.e. historically informed performance practice. Here the concert halls have taken their cue not least from festivals, which are usually held outside of concert institutions and enjoy a lively flow of visitors within a narrower temporal framework. Recently concert halls themselves have increasingly tended to mount their own little festivals within the annual season.

Another successful format is individual subscriptions, which give visitors an opportunity to make personal selections from the season programme of the house concerned. This enables concert halls to detect trends in public taste: which concerts are frequently included in the subscriptions? Which programming ideas take hold, and which fall by the wayside? The results can then be incorporated into the hall’s programming philosophy. Many concert halls also devise new series of events in order to distinguish themselves from other houses and make their programmes unique. Examples include ‘Zeitinseln’ (time islands) at the Dortmund Konzerthaus, where artists or composers are presented over a period of three to four days, and the ‘Junge Wilde’ (young savages) chamber music series, which accompanies up-and-coming talents on their road to fame. Recently the boundaries of the established concert hall repertoire have been probed again and again by purely thematic programmes, thereby creating appealing new formats: operas in concert performance, premières of new works commissioned by the house itself, famous performers-in-residence and portrait recitals. Finally, a concert hall can gain recognition value by forming permanent ties to particular artists. This notion of a ‘house ensemble’, or relatively stable group of artists, is solidified with débuts or farewell concerts, giving audiences a chance to view themselves as the hall’s ‘connoisseurs’, to identify with the hall, and ideally to experience the artist as a municipal or regional landmark.

Equally important in this context are the external publicity and marketing of the concert offerings, including addressing audiences in a manner at once up-to-date and appropriate to the respective target group. This involves not only social media but also such traditional forms as programme booklets, advertisements in regional or nationwide publications, mailings about programme highlights, artists-in-residence and customer loyalty and care, which can be attained for example by well-planned and sustained data management. Online offerings, such as the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall or Cologne’s online broadcaster philharmonie. tv, are logical additions to a house’s marketing efforts.

Audience

Music doesn’t change, but listeners do: this adage sums up the difficulty of appealing to today’s audience, for a large part of the population is made up of ‘nonlisteners’. Data from opinion polls suggests that the proportion of concertgoers in the overall population amounts to roughly 28 per cent. In the course of a year some 44 per cent of the population will attend at least one event with (primarily) classical music, meaning opera, classical concerts, organ and choral recitals, musicals, dance and ballet. [3] The age structure, educational level and social milieu of the people who attend (classical) concerts are studied on a regular basis. The resultant findings can shed light on changes in the listening public and what it expects from an event such as a classical concert. Nonetheless, it is a complex and timeconsuming task for a hall to reach listeners and interest them in its pro gramme. Statistically, attendance at classical concerts increases with age. Individually, however, it also depends on the extent to which listeners were exposed to classical music in their early family life. In short, later generations will not automatically visit a concert hall as they grow older. Consequently concert halls must find age-related ways to appeal to older listeners, the parent generation (30 to 49 years old) and the generation of children, teenagers and young adults.

The question of target group automatically involves the concert hall’s catchment area. In regions with a high density of concert halls, such as North Rhine-Westphalia, the stiffer competition makes it necessary for a concert hall to become familiar with and appeal to the audience in order to calibrate the scope of its information. The Düsseldorf Tonhalle, for instance, being located next to Essen, Dortmund and Cologne, will have to address and attract audiences in a different way than Frankfurt’s Alte Oper, which has little competition to deal with in its region. In contrast the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie, like the Berlin Philharmonie, with its large percentage of cultural tourists visiting the metropolis, has a larger scope and may therefore decide in favour of more open forms of communication.

To gain new concert audiences, it is not only important to communicate with different age groups: milieu, educational level and preferences also differ within the age groups, necessitating a wide range of offerings. In recent years ‘music appreciation’ and ‘outreach’ have become increasingly important for attracting new listeners and enticing them into the concert hall. Virtually every concert hall and orchestra is therefore concerned with giving listeners new ways to approach the works of classical music. New avenues are sought for encounters; alternative concert formats are tested. [4]

Future prospects

Concert halls are significant agents in musical policy and the cultural economy. Their expertise constitutes a prized asset particularly in pluralist 21st-century society, with its jumble of equivalent norms and values. At present, for example, it has become especially important not only to take note of social and cultural interplay, but to actively shape it and to engage with people and music from other cultures with curiosity and respect. In an age that confronts us with new challenges at every turn, the durability of concert halls is a helpful corrective: they are cultural institutions with over 150 years of experience in surmounting complex issues and dealing with social circumstances in a constant state of flux.

In this light, all musical institutions face the long-term task of becoming more sensitive to the needs of concertgoers. In past years the entire world has seen the opening of new and sometimes spectacular buildings that place a strong emphasis on external impact, as witness the concert halls in Copenhagen and Helsinki, the Philharmonies in Paris, Kraków and Budapest, or the Luxembourg Philharmonie. In Germany, too, over the last two decades innovative new buildings have arisen that add extraordinary architecture to their cities’ profiles and help to keep classical music present in the lives of their citizens, most recently the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, the Anneliese Brost Music Forum Ruhr in Bochum, Pierre Boulez Hall in Berlin and the Kulturpalast in Dresden. In the long run, however, it is not only the external appearance that is needed, but well-conceived outreach strategies for chil dren, adolescents and adults alike. The Hamburg Elbphilharmonie more than clearly demonstrates the sort of opportunities that a new concert hall offers along these lines: ten years ago the city was in danger of losing touch with the international music scene, but today this brilliant edifice, with its vision of urban and artistic renewal, has provided a fresh start. Not only is it culturally stimulating, it purposefully renewed what was once an unattractive district poorly served by pub lic transport. A similar impact was occasioned by the Anneliese Brost Music Forum Ruhr in Bochum, the construction and opening of which, in 2016, brought new magnetism to an entire urban district by incorporating the neo-gothic St Mary’s Church into its design while paying heed to Bochum’s history, and thus to part of its local identity. No less typical of the alignment of these new venues is a concern that the planners of the Bochum building expressed as follows: to give people ‘a musical home, regardless of their social origins or formal education, open for ev ery style of music with a broad range extending from cultural grassroots work to supreme artistic achievements’. [5] The goal is to offer music for everybody and thus to become a social site whose visitors will, in the long run, find a musical home within its walls.

Finally, to address various audiences in an up-to-date fashion, it is important to mention the potential of digitisation, which harbours great opportunities for classical music and the status of concert halls. Appealing web content that makes classical music constantly available and readily accessible, can be profitably combined with concert halls whose superior acoustics make possible live experiences otherwise unthinkable in the digital world. The range of online offerings in classical music extends far beyond the odd Tchaikovsky symphony occasionally found in stream ing services: many blogs and platforms specially developed for classical music enliven the market, and the wide-ranging offerings permit a lively exchange of knowledge, opinion and contents. Online offerings thus give concert halls many options for attracting greater public attention and international visibility, options that are increasingly being put to purposeful use. Despite reproductions in the media, the privilege of concert halls remains intact: they allow us to gather together with other people at a particular time and in a particular place, and to focus entirely on a work of music. Only here is music offered as a visceral experience with top-calibre musicians, superior acoustics and a high level of artistry. The union of live streaming and live experience, of round-the-clock online offerings and scheduled musical events in the concert hall, ultimately enlarges our possibilities for ex periencing classical music. It is a simultaneity that need not be decried as a ‘necessary evil’ of the 21st century, but serves as a mutually advantageous situation for both sides.

The strength of concert halls lies in the unique and unreduplicatable experience of a concert performance, and their relevance remains undiminished. True, the changes that will affect the concert industry in the future cannot be predicted; but with the uniqueness of what it has to offer, the concert hall can continue to hold its own as an endlessly adaptable cultural vehicle.

Footnotes

See also Julia Regine Rusch, Konzerthäuser in Deutschland nach 1945: Vergleichende Untersuchung zu Planung, Architektur, Akustik und Nutzung von Aufführungsstätten konzertanter Musik (Cologne, 2016), pp. 16f

See https://www.gewandhausorchester.de/haus/partner/ (accessed on 30 May 2018).

See Karl-Heinz Reuband’s essay ‘Preferences and Publics’.

See Johannes Voit’s essay ‘Music Communication’

See Benedikt Stampa, ‘Musik für alle?‘, Musikforum 3 (2017), pp. 14-18, quote on p. 16.