Music plays a variously intense role in everyone's everyday life: we listen to and make music alone or with others on quite diverse occasions, in the physical world or collaboratively, via the internet. Music surrounds us as street music from buskers, political songs at demonstrations, football chants in stadiums or is used to influence us whilst supermarket shopping. Its effects on each individual are undeniable, because music stimulates, relaxes and encourages us to express emotions. Singing in a choir, learning to play a musical instrument and making music in a band, ensemble or orchestra supports the emotional and social development of children and young people. Music connects us with others and strengthens our sense of togetherness. Although not all the positive effects that become clear in daily observation and perception have been scientifically understood to date, they justify music lessons as part of the curriculum in state schools.

At present, however, music as a school subject seems to be losing importance in Germany, as are (in consequence) the numerous voluntary music programmes at the various types of schools, from the school orchestra and choir to the professionally supervised school band. This precarious situation also includes an increasing shortage of music teachers in the coming years and the resulting loss of music lessons. At present, continuous music lessons cannot be guaranteed everywhere, both in primary or secondary schools. It is therefore not uncommon for music to be covered by another department, to be lacking at some schools or to be included in interdisciplinary courses.

In terms of content, music lessons face the challenge of meeting social conditions and the expectations of contemporary school teaching. Digitality, digitalisation and associated changes in listening and consumption habits, as well as the diversity of styles and presentation formats, question the role of the ‛traditional’ curriculum of classical Central European music in state school teaching. Music lessons are often still linked to this, although there are concepts and models in music education that have long since resolved the dubious polarisation between so-called serious and popular music. Further questions are: How can music lessons be inter-culturally and inclusively shaped in order to meet the diversity and heterogeneity of pupils in classrooms? How do the theory and practice of music and music-making relate to each other? How can music teacher training be designed to be evidence-based and future-orientated? That there are no standardised national answers to these questions is not least due to the federal system, which cedes educational sovereignty to the 16 federal states. The resulting diversity of educational policy frameworks, such as the division of the school system into a large number of different school types, makes it difficult to take stock of music teaching and music teacher training in Germany. Nevertheless, basic contours can be described.

Music as a school subject: Definition

A century ago, a paradigm shift took place in school education. The ‛singing lessons’ that had existed since the end of the 18th century were expanded and renamed ‛music lessons’ by decree in Prussia for the first time. The far-reaching music education reforms of the 1920s by Leo Kestenberg, an influential cultural politician and Music Advisor in the Prussian Ministry of Culture, affected both music lessons in state schools and music schools as well as music teacher training. Its results still characterise the music-related educational landscape in Germany today. Meanwhile, music has become more diverse than in Kestenberg’s time, therefore the content and aims of those music lessons are therefore no longer valid today. Since the late 1960s, music education has been particularly preoccupied with the question of what ‛music’ in music lessons actually means. Given the abundance of available music in a globalised and mediatised world and the associated plurality of musical forms of expression, ‛music’ in the singular no longer seems sufficient.

One way of dealing with this situation is to use the word ‛musics’. Music educator Volker Schütz asserts that we can ‟no longer speak of ‛music’ as a generally accepted and all-encompassing term”, but must instead ‟speak of ‛musics’, of a multiplication of the concept of music.” [1] The phrase ‛ music(s) education’ is intended to express an understanding of music that is not based on a universally valid value standard.

Since the 1970s, there has been a significant paradigm shift ‟from an orientation towards works to an orientation towards musical (utilisation) practices”. [2] Today, the planning and implementation of music lessons no longer centres on musical works (objects), but on what people (subjects) do with music. Consequently, listening to and understanding music from the past has not vanished from the classroom: but the renouncement of a work as the starting point for music lessons and orientation towards the learning subject recognises that pupils already engage with music. This relocates an important prerequisite when deciding what should be learnt in music lessons. This way of thinking has a lasting impact on contemporary music teaching and music teacher training.

An equally colourful term that is frequently used, not least in education policy papers, is that of musical education. It can be sharpened by the term ‛upbringing’: While ‛upbringing’ describes an intentional action in which an adult has a planned effect on a child/young person to bring about long-term effects on attitudes, knowledge and skills as well as emotions, ‟education emphasises the acquisition of knowledge and skills as guarantors of responsible and independent action.” [3] This lasts a lifetime. Above all, education is an ‟ongoing process of endeavouring to independently and autonomously explore one’s environment. ‟As object-orientation in music lessons is no longer part of modern understanding, ”musical education today (...) is no longer oriented towards a fixed stock of musical artworks. All music is potentially relevant to education” and "an occasion for diverse experiences.” [4]

In 2023, against a backdrop of critical developments, the German Music Council (DMR) emphasised in a paper entitled #SchuleNeuDenken (Rethinking School) the ‟participation in cultural communication and negotiation processes” and its contribution to the ‟interdisciplinary networking of different sciences, specialist disciplines and areas of society” as the overriding goal of music education. [5] Yet the term ‛participation’ is by no means a new concept when it refers to social participation in music culture, as is the case here. However, it no longer only refers to activities in areas of high culture such as concerts, theatre and opera, but also unfolds more multi-layered perspectives. In today’s language, participation in life in society can also refer to Book 9 of the German Social Code, which specifies the participation of people with disabilities: the basis upon which to demand inclusive music lessons, for example.

The overriding objective of music lessons, already recognisable in Kestenberg’s work, remains the same: As an indispensable part of being human, music in school lessons should not only be experienced and understood through singing, playing and creating music, but also through listening, reflecting and talking about it, as well as transforming it into movement or images.

Music education in the school curriculum

From an institutional point of view, music lessons are firmly anchored in the school system. It is part of the curriculum at primary and secondary school level and is rooted in academic discourse, yet – like other school subjects – faces educational policy challenges. These are clearly visible in the cultural sovereignty of the federal states guaranteed in the German constitution, which is extremely heterogeneous with its 16 different school and higher education laws and different political agendas.

In some cases, there are considerable differences between the individual federal states, not only in the school system but also in the curricula and, not least, in the prevailing conditions for music teacher training. The length of school life as a whole also differs, as does the respective type of school. While primary schools, for example, generally require four years, six are stipulated in Berlin and Brandenburg. The same applies to grammar schools with either eight or nine years. There are also different names for the school types. All of this has an overall impact on the timetables and the duration, reliability and sustainability of music lessons in Germany. Several federal states provide for the establishment of music grammar schools as an exceptional form of scholastic music education; in Bavaria alone, there are 14 so-called music grammar schools. These are state schools specialising in music, whilst the profiles, scope and range of courses vary. These are an important element in the promotion of musical talent.

Due to this legally diverse situation, the Ministerial Conference of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) can only create standardised conditions to a limited extent although many of its resolutions are guidelines concerning the recognising of school qualifications, educational standards or quality assurance, for example. Unlike many other school subjects, the Conference has yet to set subject-specific educational standards for music.

State schools with a focus on music

In Germany, many schools offer more music lessons than are scheduled in the curriculum or are particularly committed to instrumental or singing lessons. The aim is to support talented children and young people in their individual musical abilities as part of a general school education. How individual primary and secondary schools with a focus on music work, varies in detail depending on the type of school and federal state.

Objectives and content of music education

In general, today’s music lessons follow a teaching principle that takes musical-aesthetic perception and experience as the starting point for understanding oneself and the world, as well as a specific practical understanding. The (musical) environment of the class members is included in the planning and realisation of lessons. This rests on a concept of learning that assumes that people construct or negotiate their perception and understanding of the world in interaction with others, i.e. when talking about or creating music (together). Since pupils, as explained above, are practised in the use of music, and it is a ‟substantial and integral part of their way of life without their being consciously aware of it”, they should – in lessons with the various forms of dealing with music (e.g. reception, reflection, transformation, production) – be able to ‟consciously incorporate musical activity into their lives as constitutive of this way of life”. [6] Assuming, therefore, that all pupils already engage with music in their own way, the task in music lessons is not simply to teach them musical knowledge and experience on the assumption that they know nothing about it. The opposite is the case. They already interact with music, and this interaction can be the start and connection point for expanding and deepening knowledge and skills. This stance gives rise to the expectation that music teachers should recognise and value existing usage practices and transform them into informed musical engagement. This expectation can be illustrated by classroom music-making.

Music-making with school classes or class music-making has resumed playing an increasingly important role in music lessons for some time now. Numerous models and concepts convey a practical approach to different styles and aspects of music history or illustrate general music theory. Making music is also important for initiating creative (design) processes and generating musical-aesthetic experiential spaces because when making music together, pupils see themselves as being musically effective. It can be said that classroom music-making – i.e. practical music activities in school music lessons – ultimately promotes individual skills on instruments or vocally and can stimulate or deepen interest in musical engagement. However, the practical music-making skills and abilities thus acquired do not yet lead to informed engagement with music. Only when that which occurred while making music together is also reflected upon, i.e., combined and enriched with knowledge, does informed musical engagement emerge.

Here is where the term ‟proficiency” comes into play. It emphasises that the goal of learning is not merely the collection of knowledge but the active acquisition of knowledge and skills to successfully master tasks or challenges in unknown situations and to carry out activities effectively (proficiencies). Although proficiency-orientation has determined objectives, performance and didactic action in all subject didactics and teacher training since around 2000, there are reservations about this style of thinking. They are rooted primarily in the conviction that the specific aesthetics of music-related teaching/learning processes cannot be depicted in this way, meaning that this focus leads to reduction into linguistic statements about music.

The question of which proficiencies pupils acquire in music lessons at the individual school levels is as much a focus of music education research as it is of curriculum development. This is because the shift towards proficiency-orientation has also changed the state specifications of educational objectives in the (core) curricula, framework curricula, educational plans and core curricula of the 16 federal states. [7] These also differ not only in their names but also in their structure. The reference to a common or specific understanding of proficiencies is also expressed and reinforces the heterogeneous conditions in German music education at the content level. What curriculum and syllabus developers understand by ‛proficiencies’ is sometimes quite diverse. For example, the education plan in Baden-Württemberg for secondary level I distinguishes between process-related and content-related proficiencies, [8] while the core curriculum of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia for the same school level formulates musical-aesthetic and action-related proficiencies. [9] In the recently published educational principles of the same state, it is pointed out that the focus of ‟proficiency-oriented teaching (...) is on the learning outcomes – also in the sense of learning processes – of the pupils”. [10] The curriculum from Schleswig-Holstein distinguishes between two subject-specific and three interdisciplinary areas of proficiency (personal, social and methodological proficiency). [11] The subject-specific areas of proficiency are also different. In Baden-Württemberg, there are three (creating and experiencing music, understanding music, reflecting on music), in North Rhine-Westphalia three (reception, production, reflection) and in Schleswig-Holstein two (creating music, exploring music).

Inter-/transcultural music education

Through the above-mentioned understanding of music and proficiency-oriented thinking, music lessons can also make a specific contribution to numerous cross-sectoral social issues, e.g., interculturality, digitality and digitalisation, inclusion or democracy and anti-racism education.

The terms inter-, multi- and transculturality have played an important role in German subject debates over the last 40 years regarding music lessons. Music from other parts of the world and a focus on (alleged) migration cultures in music lessons can be found in textbooks, teaching materials and in music education discourse, sometimes from controversial perspectives. At present, such endeavours are occasionally accused of being ethnocentric, post-colonial, racist or cultural appropriation when addressing music from other cultural contexts or focussing on the (assumed) music of migrants in classrooms. This raises the question of whether music lessons about other music or the assumed music-cultural contexts of pupils with a migration background are the right way to deal with the existing diversity of environments and music practices. Under certain circumstances, this could result in unconsidered eurocentric and ethnocentric views or the reinforcement of existing stereotypes. This is where so-called ‛culturally sensitive’ music lessons come in. This way of thinking not only influences lesson planning but also music teacher training. The latter is currently endeavouring, for example, to incorporate musical instruments other than the familiar ones into teacher training courses; additionally, music teachers with a migration background hardly ever become music teachers at school, partly due to the music-related selection process at the beginning of their studies (aptitude test), common in many places.

Diversity, digitalisation and digitality

Inter-or transculturality and diversity are just two of many cross-sectional topics in state music education from the perspective of proficiency-orientated objectives. Digitality and digitalisation are equally present in current music didactic debates. While digitality is described ‟as a subjective or social relationship between subjects and digital artefacts”, also leading to a change in perceptions of materiality or mediality, digitalisation refers to processes of change such as the ‟transfer of information from an analogue to a digital form of storage” or the initiation of digital transformation processes in institutions. [12] Both aspects are highly relevant for music lessons, as the 2017 study Digitale Medien im Musikunterricht (Digital Media in Music Education) by Michael Ahlers showed. [13] According to the latest Shell study from 2019 ‟96% [of young people] use social media (messenger services or social networks) at least once a day. Although 76% go online at least once a day for entertainment purposes (be it for music, video streaming, gaming or viewing posts by people they follow), 71% also search for information at least once a day (of a general nature, for school, training or work or about politics and society).” [14]

Professional industry associations have reacted to the use of digital media, as it has long since become a practice that influences music-educational thinking about music. For example, in its 2019 policy statement, the Bundesverband Musikunterricht (German Federal Association for Music Education, BMU) comments on the development of music education in the age of digitalisation and highlights in particular ‟the permanent connectivity in the digital world and the resulting changes in the way we deal with the aesthetic values of music”. [15]

Literature points out that digitalisation should not stop at the mere use of tools in music lessons. Both the initiation of a media-critical attitude – for example, concerning the music industry interests of corporations – and copyright aspects should be taken into account in music lessons. Numerous models support this, such as the SAMR model developed by Ruben Puentedura in 2006, which supports teachers in the digitalisation of their lessons by providing decision-making aids for the use of digital media such as OER (Open Educational Resources) or paid apps based on the four criteria of substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition. The teacher must – in consequence – consider whether an app substituting for a carillon is appropriate for their class and their set teaching objective, whether the app extends the instrument or whether it can take on a new meaning for the teaching project. The topics of digitality and digitalisation also influence the curricula. The State of North Rhine-Westphalia, for example, has developed a media literacy framework for all school subjects, which also serves as a guideline for the subject of music. [16]

Cooperative music lessons

The idea of a school as a living and working community has its roots in the progressive reformative pedagogy of the early 20th century but is still of great importance in some types of schools today. Music not only plays an important role in these but the performative educational potential of such activities must also be understood as part of the educational mission of schools. They take place in various formats and are ‟music as an activity [...] without any claim to curricular legitimisation”. [17] These activities, commonly referred to as extra-curricular events or study groups (AG), , for example, in the form of choirs, bands and orchestras, also characterise the image of a school. Initiatives such as Schulen musizieren (Schools make music) not only facilitate competition at state and national level but are also an important element of school networking.

Two domains can converge in the AGs: amateur music-making, which often takes place in free time, outside the school context, and the school as a place of learning, where performance in the study groups is often rewarded. For example, a representative survey on amateur music-making in Germany published in 2021 shows just how important school is as an opportunity or sphere for musical involvement. The authors state that ‟most amateur musicians found their way into music through school, a choir, private lessons or through family or friends”, with ‟36 per cent of all amateur musicians aged 6 and over (...) first coming into closer contact with musical activity at school”. [18]

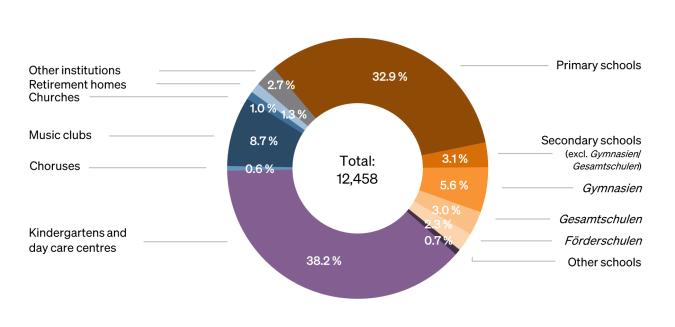

For some time now, schools have increasingly found support from music schools, music clubs and various regional or local initiatives that are involved with music. At first glance, music schools seem to be a natural cooperative partner for state schools, as the focus is primarily on making music in various constellations. It is only logical that federal and state initiatives such as "Jedem Kind ein Instrument" (An Instrument for Every Child), JeKi: 2007-2018, and their follow-up and accompanying projects have had a lasting impact on schools. The Association of German Music Schools (VdM) alone reports almost 12,500 collaborations with various educational institutions, with primary schools accounting for the largest share of these collaborations at 32.9 per cent and preschool institutions at 38.2 per cent (see figure 2).

In this context, it is important to emphasise two details: Firstly, the programs offered by the public music schools in the VdM (Association of German Music Schools) and the independent music schools (bdfm), for which no figures are currently available, are at best a supplement to general music lessons for schools, but not a substitute. Secondly, music education does not only take place in music schools. Other stakeholders such as regional music clubs, choirs or brass bands organised in the Bundesmusikverband Chor & Orchester (Federal Music Association for Choir & Orchestra, BMCO) are also effective partners for schools. For example, the interests pursued in promoting scholastic and educational development by implementing full-day schools are legitimately linked to the interests of the respective extracurricular partners in promoting young talent. In addition to equally necessary selective projects, cooperation from the perspective of scholastic development must always be considered in terms of the profile-building interests of the respective school. This is particularly important in the full-day primary school sector because learning psychology provides no expedient reasons for separate consideration of morning and afternoon lessons. Nor is the school and its state-given educational assignment any less effective in afternoon lessons. Admittedly, this gives rise to problems that affect music teacher training, as discussed further below.

Music education in numbers

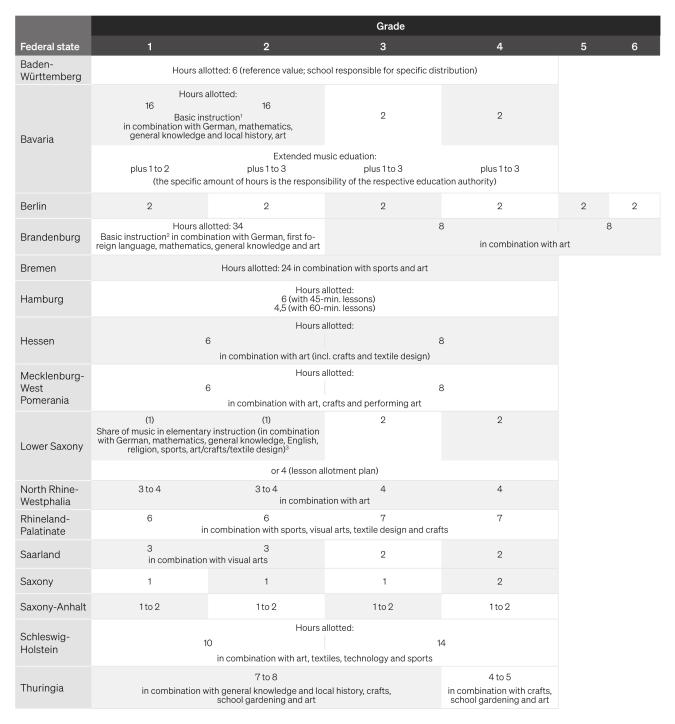

More than the right to education in the German Federal Law, derived from the individual regulations of Art.2 Para.2 and Art. 7 Para.1, the fundamental right to music lessons for pupils of all school types and grades can be derived from Art. 22, but especially Art. 26 and Art. 27 of the Convention on Human Rights and Art. 39 of theConvention on Children's Rights. That those responsible for education policy and their subordinate executive bodies pay varying degrees of attention to this state of affairs is documented not only by surveys on lesson cancellations but also by comparisons of timetables. This is particularly the situation in primary schools. Figure 2 shows that the quota of music lessons provided for in the individual federal states is assessed mostly in conjunction with and thus in competition with other subjects; only in Berlin, Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt is music shown separately.

In addition to a visible state-specific hyper-complexity, the range of the individual totals is striking. These findings reveal heterogeneous conditions in the federal states. However, this does not provide any information about the situation at the respective schools.

A Bertelsmann study from 2020 presents a differentiated picture of the situation at primary schools, not only confirming a high level of teaching absenteeism but also a significant associated shortage of teachers. Among other statements, the authors relate (for Germany as a whole) that ‟there is a shortage of 23,147 fully qualified primary school teachers. On a national average, only 42.8 per cent of compulsory music lessons – and thus significantly less than half of the prescribed lessons – could be taught by music teachers”. [19] Even with a positive forecast of demographic data and assumed student numbers, the authors continue, ‟nothing will change in terms of the inadequate provision level of professional teaching in music overall”; rather, it is to be expected that ‟the shortage of music teachers will continue to worsen if countermeasures are not taken quickly”.

The response to the desolate situation at this type of school is usually music lessons being taught by teachers without a qualification in music education or being exclusively understood as substituted in project forms that are not always sustainable. However, sustainably strengthening these schools is only possible with a joint effort by schools and universities and requires sufficient financial resources. [20]

Comprehensive studies for the two secondary levels are still lacking. However, a comparative look at the music timetables at the lower secondary level (2023) [21] is likely to produce similar results, with the degree of diversification extending not only to specific institutions but also to the teaching format. Music lessons are offered as a compulsory, elective or profile subject or – in music-orientated school types – in-depth.

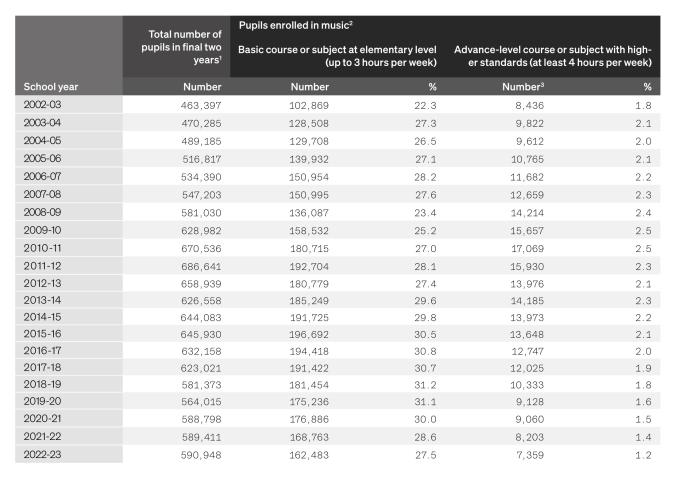

As figure 3 shows, the number of advanced music courses has been declining since the 2009/10 school year, defined as Q1 and Q2 at an eight-year or 12th and 13th grade at a nine-year grammar school, depending on the federal state. The number of basic courses has also been falling in recent years. What role the pandemic has played in the declining numbers is as unclear as the reasons for this development, apart from speculation.

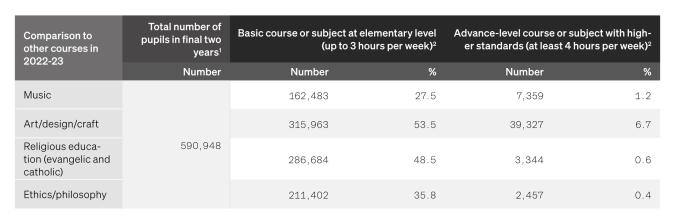

A statistical comparison with other subjects for the 2022/23 school year (cf. figure 4) clearly shows that the number of pupils enrolled in music lessons is lower. It is striking that following the subject of art with 39,327 pupils, the advanced music courses were taken by 7,359 pupils. More pupils chose music as a subject than religion and ethics/philosophy.

The reliability and sustainability of music lessons at state schools can also become uncertain due to cooperative models. This is particularly evident when instrumental courses (e.g., wind or string classes) interrupt music lessons for only some pupils over a fixed period or when these programmes take place without any connection to music lessons. Just as JeKi's accompanying research has already pointed out difficulties in the inter-professional cooperation between music school teachers and teachers at schools, [22] additional coordination problems often arise in models with, for example, two-year interruptions, especially if only part of the class takes advantage of them.

Given this situation, professional and interest groups have repeatedly and emphatically emphasised the need for action on the part of education policy decision-makers. In 2019, the BMU (Federal Association of Music Teachers) took a firm stance on the content and staffing of music lessons in primary schools. In this context, it calls for music to be taught as a specialised subject, for teachers to receive the same pay as their colleagues at secondary schools and makes proposals for reforming music teacher training. [23] Given the results of the 2020 Bertelsmann study, the German Music Council has formulated similar expectations of all education policy stakeholders with its 2020 #MehrMusikInDerSchule (More Music in School) initiative. [24] A commitment in this direction can be traced back to the 1950s and to the first memoranda on music teaching [25] after the Second World War, although in historical retrospect it is surprising how similar the topics and demands sometimes are.

This observation leads to the conclusion that the existence of music lessons in particular is increasingly under pressure to be justified.. The challenge for music as a subject is, amongst others, to confront arguments that question or reject compulsory music lessons for all pupils, i.e., that see music as exclusively anchored in the leisure sector or as a talent subject. Arguments such as these – as already indicated above – reduce the fundamental questions about what general education schools and their curriculum have to achieve in a liberal, democratic society. That music is seen as a private matter or leisure activity justifies its educational relevance in light of the above. This is shown not least by the results of surveys on leisure behaviour. [26] According to these, engaging with music, especially listening to music, is an important activity. [27]

While artistic activities such as making music, writing, writing poetry or painting decline with increasing age, listening to music is considered to be very important throughout all phases of life. [28] A similar picture emerges regarding event attendance. [29]

Music is present in everyday life as a multifaceted practice and is just as stylistically differentiated as the formats in which it takes place. It has meaning for people and therefore, in principle, has educational potential to connect to, be expanded and deepened.

Music teacher training in terms of content and structure

As explained above, an understanding of music education as an introduction to so-called classical music is no longer tenable. This has implications for music teacher training, which has some particularities compared to other school subjects. On the one hand, in addition to the general higher education entrance qualification, a multi-part examination determines suitability for the respective teacher training programme at the chosen institution. On the other hand, study programmes are as diverse as possible, i.e. locations emphasise specific subject areas with their respective curricula in a more academic or didactic way or give more or less space to artistic practice. The scope and timing of the practical phases also vary. Although the Ländergemeinsame inhaltliche Anforderungen für die Fachwissenschaften und Fachdidaktiken in der Lehrerbildung (Common Content Requirements for Subject-Specific Sciences and Subject-Specific Didactics in Teacher Education) [30] – last revised by the KMK (The Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs) in 2019 – differentiate both a subject-specific competence profile and the content areas for music teacher training, a cursory analysis of the degree programmes reveals a great deal of heterogeneity in their implementation. Although it is ‟in principle to be welcomed, as student teachers may be given opportunities to strengthen their interests and skills during their student life cycle” , [31] it makes music teacher training hardly comparable both at the state level and, in particular, at the federal level. Mutual understanding is also complicated. Despite this heterogeneity, it is possible to identify core areas that were already guiding music teacher education before the KMK recommendation, as some of them can already be found in Kestenberg’s work:

- Since Kestenberg, musical practice (or: artistic practice) and music theory have actually referred to a whole package of skills consisting of general music and form theory as well as various music-making practices, individually and in groups. In addition to a wide range of instruments and styles offered at many institutions, composition or digital music production can now be studied as a core or major artistic subject. Singing is a central music practice in all degree programmes. It addresses similar competences to speaking or speech training.

- Apart from music education itself, the academic reference disciplines for music teacher training are, in the classical sense, the disciplines of historical and systematic musicology, which were established in the 19th century through professorial chairs, as well as ethnomusicology (or music ethnology) as the successor to comparative musicology, which was established around 1900. There are also links to music theory (with aural training) as a further, more artistic-scientific discipline. Not least, cultural studies and sociology have triggered developments within these subjects. These increasingly raise the question of the relevance and presentation form of their respective content for music teacher training, particularly against the background of proficiency orientation and the above-mentioned fundamental ideas of music as a social practice.

- Since the 1906s, music education has been represented by professorships. At its centre are appropriation and mediation processes in the relationship between people and music. Music didactics as a variety of music education – like all specialised didactics – has the tasks of analysing, planning and staging music lessons; it is no longer limited to the didactics of the illustration of mostly historical musicology, as was common until the late 1950s. Since the so-called empirical turn at the latest, educational sciences, having taken up a large part of teacher training in recent years, have become a further pedagogical reference science.

Both a divisive understanding of so-called artistic practice versus specialised sciences with music education and an object-oriented, normative concept of (music) culture are mostly considered outdated. This has been articulated several times and from different perspectives, since the 1990s at the latest, meaning that music teacher training programmes need to cover a broad range of academic and practical music subjects. Future music teachers must be able to expand and deepen their own (music-related) proficiencies with a critical and reflective view of the professional scholastic field. This is the only way to initiate professionalisation processes which may reform schools.

As practical music-making skills and abilities are at the heart of music teacher training, it was common practice for a long time for prospective students to study for the grammar school teaching qualifications at conservatoires and for primary, secondary and lower secondary schools at teacher training colleges or, after their dissolution (except in Baden-Württemberg), at universities. With the educational reforms of the 1970s, this strict separation was abolished, so that, today, grammar school teaching qualifications can also be studied at universities as a single subject or major subject (music only) as well as a double or dual subject (music and another subject).

With the Bologna Declaration of 1999, a degree structure reform was carried out in which the previous degree titles (Diplom, Staatsexamen) were generally replaced by Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees; some federal states (Bavaria, Hessen, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Saxony) continue to offer the Staatsexamen. In 2004, the Rektorenkonferenz der deutschen Musikhochschulen (Rectors’ Conference of German Music Universities, RKM) decided that all music universities would offer a four-year Bachelor’s degree in future, as ‟it is not possible to obtain an artistic or music education qualification within three years that would enable graduates to survive on a demanding labour market”. [32] The common structural guidelines of the federal states for the accreditation of Bachelor's and Master's degree programmes [33] adopted this accordingly – with consequences for music teacher training: This led to different structural framework conditions for the teacher training programmes in music, which take place at academic and pedagogical universities as well as at music universities, or Musikhochschulen.

For some time now, the shortage of music teachers, not only at the primary level, has become increasingly evident. Data from the Federal Statistical Office for the winter semester 2022/23 shows, on the one hand, that the teacher training programme ranks quite high in the tableau of music professions at 24.4 per cent. [34] On the other hand, it is noticeable that student numbers at the institutions for music teacher training are stable overall. [35] While musicology has seen significant losses in student numbers, the music teacher training programmes recorded around 7,700 enrolments in the winter semester 2022/23 and thus remain the second most popular music study subject in Germany.

Although data for subsequent years is not yet available, music education associations in various places are in some cases reporting a significant drop in the number of applicants. To understand why, investigations are currently being carried out at numerous locations in Germany, to be summarised in a meta-study in spring 2024. The hypotheses range from declining interest in music-making, triggered by the pandemic for example, to demographic effects and the question of the image of music teachers. There being a lack of reliable data, we may only speculate about the reasons. It is striking that numbers at individual locations are unevenly distributed, meaning that individual locations are considering reforming the aptitude assessment procedure and their degree programmes.

Outlook

Music lessons in state schools have been an educational and cultural achievement for 100 years. From the singing lessons that prevailed until then, the qualitative leap cannot be overestimated, because inclusion in the curriculum recognises that it is possible to understand the world and oneself with and through music. Music is what people do: They invent, produce, use and consume it. Music as a social practice is used to form and propagate opinions, to protest and manipulate. People use music to express their own emotions in a specific and hardly comparable way. Music can structure thought and action, it expands the perception of time and space, of history and the present. In short, music lessons in state schools in the 21st century are more relevant to education than ever before. Two aspects should be emphasised as perspectives for the future:

- Music creators have been reacting to digitalisation, digitality and artificial intelligence for some time now. They are part of a long tradition that goes back at least as far as the musique concrète of the 1940s. Pupils use playlists to shape their approach to music. They use digital and analogue musical instruments to produce and publish music. This practice should be recognised and must help shape music educational thinking about music: not based on a naïve understanding of environmental interconnection but with an educational claim, i.e., with the claim to consider this approach both creatively and with critical reflection in lesson planning and implementation.

- Music teacher education must respond to prospective students today having expanded skills and abilities that include mediatised musical practices. Such practices should not be selected via exclusive and excluding aptitude assessment procedures. Simultaneously, a broad range of study programmes should be made possible. There are hardly any students with a migration background enrolled in music teacher training programmes. This is a symptom of a still prevalent, normative understanding of music and its exclusionary mechanisms. This image must be corrected in the future.

In the understanding of music education summarised above, a state school curriculum without it is unimaginable. If it were to be omitted, the fundamental question of what it means to be and become human would arise in schools. Music lessons at school aim to strengthen all pupils in their interaction with music, to broaden these multi-layered relationships with music and to unlock new ones. It is no less elitist than sport, art, religion or politics and no less important than maths, German and biology because listening to, making, speaking about and transforming music is used both to acquire experiences and knowledge about the world and to practise attitudes towards it. These are qualities and tasks that – like music itself – are of the utmost importance in a fragmented world.

Footnotes

Volker Schütz, ‛Welchen Musikunterricht brauchen wir? Teil 1: Klärung einiger Voraussetzungen, in: AfS-Magazin 1 (1996), p. 4, online at https://www.bmu-musik.de/fileadmin/Medien/BV/Archiv_AfS/AfS-Mag01_Schuetz..pdf (accessed on 15. January 2024).

Werner Jank, ed., Musikdidaktik. Praxishandbuch, (rev. 9th edn., Berlin, 2021), p. 62.

Rudolf Dieter Kraemer, Musikpädagogik. Eine Einführung in das Studium (Augsburg, 2017), p. 81.

Jürgen Vogt, ‛Musikalische Bildung’, in: Michael Dartsch et al., eds., Handbuch Musikpädagogik. Grundlagen – Forschung – Diskurse (Münster et. al., 2018), pp. 31-37, esp. p. 36.

Deutscher Musikrat, #SchuleNeuDenken: mehr Musik! (Berlin, 2023), p.1 (accessed on 17. January 2024)

Hermann Josef Kaiser, ‛Musik in der Schule? – Musik in der Schule! Lernprozesse als ästhetische Bildungspraxis’, in Zeitschrift für Kritische Musikpädagogik (2002), pp. 1-12, esp. p. 11.

See the curricula of the individual federal states under https://www.bildungsserver.de/Lehrplaene-400-de.html (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See Ministerium für Kultus, Jugend und Sport Baden-Württemberg, ed., Gemeinsamer Bildungsplan der Sekundarstufe 1 (Stuttgart, 2016) online at https://www.bildungsplaene-bw.de/site/bildungsplan/get/documents/lsbw/export-pdf/depot-pdf/ALLG/BP2016BW_ALLG_SEK1_MUS.pdf (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, ed., Kernlehrplan für die Sekundarstufe I Gymnasium in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Musik (Düsseldorf, 2019) online at https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/lehrplaene/lehrplan/207/g9_mu_klp_%203406_2019_06_23.pdf (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See Bildungs- und Erziehungsgrundsätze für die allgemeinbildenden Schulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Entwurf Verbändebeteiligung, 18.08.2023, p. 13, online at https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/lehrplaene/upload/RiLi2023/Entwurf_RiLi_VerbBtlg_2023_08_18.pdf (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See Ministerium für Schule und Berufsbildung des Landes Schleswig-Holstein, Fachanforderungen Musik. Allgemein bildende Schulen, Sekundarstufe I, Sekundarstufe II (Kiel, 2015), online at https://fachportal.lernnetz.de/sh/fachanforderungen/musik.html (accessed on 15. January 2024).

Nadia Kutscher, ‛Digitalität, Digitalisierung und Bildung’, in Ullrich Bauer, Uwe H. Bittlingmayer, Albert Scherr, eds., Handbuch Bildungs- und Erziehungssoziologie (Wiesbaden, 2022), pp. 1071-1087, esp. p. 1072.

Michael Ahlers, Digitale Medien im Musikunterricht (2017), online at https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/Projekte/Musikalische_Bildung/MuBi_Expertise_Digitale_Medien_im_Musikunterricht_Ahlers_01.pdf (accessed on 15. January 2024).

Mathias Albert et al., Jugend 2019. Eine Generation meldet sich zu Wort, 18. Shell-Studie (Weinheim et al., 2019), p. 30.

Bundesverband Musikunterricht, ‛Musikunterricht und Digitalisierung. BMU-Position zur Entwicklung des Musikunterrichts im Zeitalter der Digitalisierung’, in BMU-Positionen 1 (2019), p. 2 (accessed on 17. January 2024).

Medienkompetenzrahmen NRW, online at https://medienkompetenzrahmen.nrw/medienkompetenzrahmen-nrw (accessed on 12. January 2024).

Kaiser, Musik in der Schule? (see note 6), p. 2.

Deutsches Musikinformationszentrum, Amateurmusizieren in Deutschland. Ergebnisse einer Repräsentativbefragung in der Bevölkerung ab 6 Jahre (Bonn, 2021), p. 19 (accessed on 15. January 2024).

Andreas Lehmann-Wermser et al., Musikunterricht in der Grundschule. Aktuelle Situation und Perspektive (Gütersloh, 2020), p. 108 (accessed on 11. January 2024).

Ibid., p. 109.

See. the statistics ‛Stundentafel Musik in der Sekundarstufe I’ (2023) of the German Music Information Centre (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See for example Ulrike Kranefeld, ed., Bildungsforschung, vol. 41:Instrumentalunterricht in der Grundschule. Prozess- und Wirkungsanalysen zum Programm Jedem Kind ein Instrument (Berlin, 2015), online at https://www.bmbf.de/SharedDocs/Publikationen/de/bmbf/3/31111_Bildungsforschung_Band_41.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 22. January 2024).

See Bundesverband Musikunterricht, ‛Musikalische Bildung in der Grundschule. BMU-Position zur inhaltlichen und personellen Ausgestaltung des Musikunterrichts an der Grundschule’, in BMU-Positionen 3 (2019), p. 4 (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See Deutscher Musikrat, Forderungspapier #MehrMusikInDerSchule (Berlin, 2020), online at: https://miz.org/de/dokumente/forderungspapier-mehrmusikinderschule (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See for example Verband Deutscher Schulmusiker, ‛Zur gegenwärtigen Lage der Musikerziehung. Denkschrift des Verbandes Deutscher Schulmusiker’, in Musik im Unterricht, vol. 40(1), (1949), pp. 3-4.

See for example Freizeit-Monitor 2023: Die beliebtesten Freizeitaktivitäten der Deutschen, Forschung aktuell, 301 (2023), online at https://www.stiftungfuerzukunftsfragen.de/freizeit-monitor-2023-die-beliebtesten-freizeitaktivitaeten-der-deutschen (accessed on 12. January 2024); Nora Gaupp, Anne Berngruber, ‛Freizeitaktivitäten von Kindern und Jugendlichen’ in Datenreport 2021, online at https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/zahlen-und-fakten/datenreport-2021/familie-lebensformen-und-kinder/329613/freizeitaktivitaeten-von-kindern-und-jugendlichen/ (accessed on 22. January 2024).

See the statistics ‛Freizeitaktivitäten in Deutschland’ of the German Music Information Centre, figure ‛Freizeitaktivitäten nach Lebensphasen 2023: Künstlerische Beschäftigung und Hörgewohnheiten’ (accessed on 29. January 2024).

For individual music preferences, see for example the statistics ‛Bevorzugte Musikrichtungen nach Altersgruppen’ of the German Music Information Centre (accessed on 12. January 2024).

See the statistics ‛Freizeitaktivitäten in Deutschland’ of the German Music Information Centre , figure ‛Freizeitaktivitäten nach Lebensphasen 2023: Events besuchen’ (accessed on 29. January 2024).

Sekretariat der Kultusministerkonferenz, Ländergemeinsame inhaltliche Anforderungen für die Fachwissenschaften und Fachdidaktiken in der Lehrerbildung, (Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 16.10.2008 i. d. F. vom 16.05.2019), (Berlin, 2019).

Bernd Clausen, Judith Wolf, ‛Musiklehrkräftebildung modelliert. Studiengänge und ihre Architekturen’, in Bernd Clausen, Gerhard Sammer, eds., Musiklehrer:innenbildung. Der Student Life Cycle im Blick musikpädagogischer Forschung (Münster, 2023), pp. 127-151.

Hochschulrektorenkonferenz, ed., Die deutschen Musikhochschulen. Positionen und Dokumente, vol. 3 (Bonn, 2011), pp. 31-32.

Ländergemeinsame Strukturvorgaben für die Akkreditierung von Bachelor- und Masterstudiengängen (Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 10.10.2003 i.d.F. vom 04.02.2010), online at https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2003/2003_10_10-Laendergemeinsame-Strukturvorgaben.pdf (accessed on 15. January 2024).

See the statistics ‛Studierende in Studiengängen für Musikberufe’ of the German Music Information Centre , figure ‛Studierende in Studiengängen für Musikberufe: 1.-, 2.- und 3.-Fachbelegungen im Wintersemester 2022/23’ (accessed on 29. February 2024).

See the statistics ‛Studierende in Studiengängen für Musikberufe’ of the German Music Information Centre, figure ‛Entwicklung der Studierendenzahlen (1.-, 2.- und 3.-Fachbelegungen) in den einzelnen Studienrichtungen seit dem Wintersemester 2000/01’ (accessed on 29. February 2024).