Germany has more than 150 museums devoted to musicians, musical instruments, regional music history or ethnomusicology. Among their aims are to collect, conserve and communicate the posthumous estates of famous composers or performers; to present, document, contextualise and research the products of musical instrument builders; and to explore regional and historical aspects of musical culture. In the case of such preeminent composers as Heinrich Schütz, Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven and Johannes Brahms, the preservation, cataloguing and communication of their posthumous effects reflect not only their historical significance in Germany, but the importance of their music in today’s international repertoire altogether. Accordingly, one of the tasks of museums is to cultivate the memory of such towering figures and to shed light on their working environment and historical surroundings. Only when their music is illuminated in educational programmes, special exhibitions and concerts is it possible to gain an understanding and appreciation of our cultural heritage, and thus to kindle interest in the on-going cultivation, conservation and fresh interpretation of the artefacts of musical culture.

Many composers have drawn inspiration for their music not least from the musical instrument industry, which set new historical standards as it evolved. Museums thus have the mission not only to document the life and works of major figures of music history, but also to conserve and update valuable collections of musical instruments, many of which date back to the 19th century or even earlier. Music museums and instrument collections are similar in that both offer objects, sources and knowledge of inestimable value to the study of music. Today many museums, besides housing and cataloguing their collections, also conduct active research programmes as varied and manifold as the sources and objects they preserve, ranging from the study of materials to the exploration of their provenance.

‘One challenge faced by all music museums is the proper conservation and presentation of their collections.’

Museums devoted to musicians

Germany has some 55 museums and memorial sites with holdings reflecting the life and work of musicians, in most cases composers. These ‘musician museums’ are often located in the places where the artists worked or were born and illuminate their social and cultural surroundings by displaying their personal furniture (or furniture from the same period), paintings, busts, memorabilia, musical instruments, autograph scores, letters and other original documents. Frequently their activities are supported by non-profit associations that sometimes also function as the museums’ sponsors.

Recent years have witnessed the emergence of new memorial sites, such as the Scharwenka Foundation with its cultural forum, archive and museum in Bad Saarow. Between 2012 and 2014 the house that Xaver Scharwenka built in 1910, and in which he lived to the end of his days, was reconstructed by the community in conjunction with the Scharwenka Foundation to create the first musician museum in the state of Brandenburg. It is funded largely from donations, as is its archive with printed sheet music, correspondence and other testaments to the activities of Xaver, Philipp and Walter Scharwenka. Another new facility is the 'Ostrockmuseum' (Eastern Rock Music Museum) in Kröpelin, which opened in 2015 with a collection of sound recordings, original instruments and technical equipment from the former state of East Germany. Also currently planned is a thorough renovation of the former residence of Robert and Clara Schumann in Düsseldorf, which will give rise to a modern museum devoted to the life and works of these two artists.

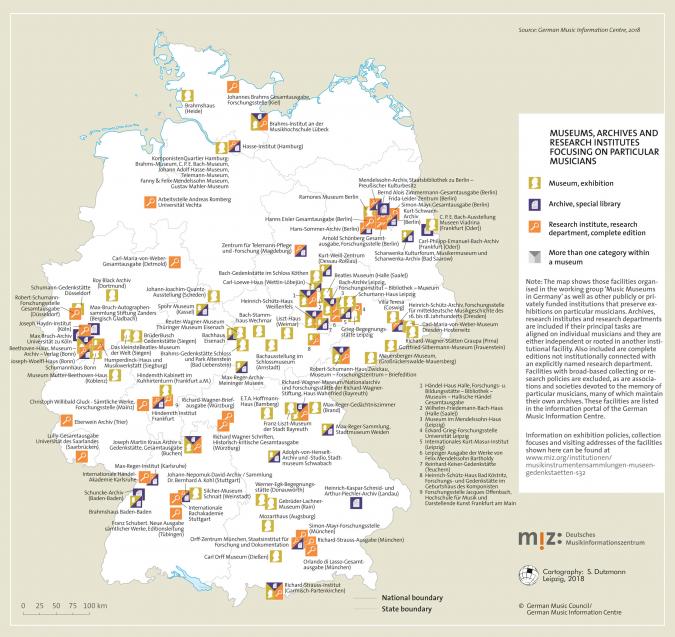

Some musician museums are accompanied by specialised archives and research institutes to document, preserve and disseminate the artist’s musical legacy, to collect and study manuscripts and other sources, to issue complete editions, separate prints and publication series, to encourage publications and to carry out digitisation projects. Institutes of this type with an international presence include the Beethoven House in Bonn, the Leipzig Bach Archive, the Handel House in Halle, the Robert Schumann House in Zwickau, the Richard Strauss Institute in Garmisch-Partenkirchen and the Richard Wagner Museum with national archive and research centre in Bayreuth.

Many private individuals, societies, foundations and citizens’ initiatives have devoted themselves to the preservation and rebuilding of historical sites where important musicians formerly lived and worked. They seek support for their projects from the public sector. The Weimar Bach Society, for example, has undertaken to build a memorial site in Weimar above the extant renaissance cellar of Bach’s former place of residence. In this way the society hopes to create greater public awareness of Weimar’s significance as Bach’s place of employment, to strengthen the residents’ sense of identity with their city and to appeal to tourists. These two viewpoints – to create a sense of cultural identity and to exploit the market for cultural tourism – are of key importance to many musician museums.

In an effort to achieve greater public visibility, many musician museums have revised the way they display their holdings and modernised and/or enlarged their premises. The recent construction or remodelling of buildings reflects a change both in museum education and in the importance attached to these buildings today. The Wagner Museum in Bayreuth, to take an example, has remodelled the Villa Wahnfried and created, alongside Wagner’s residence, a translucent glass-and-steel museum in sharp architectural contrast to the neighbouring villa. The aim of the museum is to turn the aura of Wagner’s place of work and residence into a living experience while reminding visitors of Bayreuth’s ambivalent impact on history.

In anticipation of the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth in 2020, the Beethoven House in Bonn is preparing a new permanent exhibition in spatially en larged premises scheduled to reopen in December 2019. The new conception fore sees not only an up-to-date thematic approach to Beethoven but a separate area for temporary exhibitions, a treasure chamber with original manuscripts, a music room for recitals and a seminar room for educational offerings.

A unique bundling of synergy has been successfully achieved in Hamburg by ‘KomponistenQuartier’, an ensemble of museums devoted to the composers Johannes Brahms (since 1971), Georg Philipp Telemann (since 2011), Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Johann Adolph Hasse (both since 2015). In 2018 this complex was expanded to include exhibitions on Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn and Gustav Mahler. The sponsoring organisation, KomponistenQuartier Hamburg, was initiated by the Carl Toepfer Foundation in conjunction with several composers’ societies under the aegis of the conductor Kent Nagano. The goal of the initiative is to convey Hamburg’s importance to music history and to underscore its impact on the city’s musical and cultural life today, from the new Elbphilharmonie concert hall to the Reeperbahn Festival. KomponistenQuartier is supported by a broad array of donors and civic organisations. A similar approach is sought by the Notenspur Association in Leipzig, a pooling of private individuals, associations, institutions and local businesses to turn the city’s music history into a living experience. In 2012 a system of guided walks between memorial sites opened in the city centre. Further projects were also carried out, all serving to anchor music within the city’s urban development. Finally the initiative actively helped nine music heritage sites in Leipzig to apply for the Seal of European Cultural Heritage, which was awarded to four of the city’s composers’ houses in March 2018.

In contrast, artists and composers expelled or murdered during the Third Reich continue to receive short shrift. Exceptions include Leipzig’s Notenspur, which has taken up the subject of Jewish musical culture, the Busch Brothers Memorial Site in Siegen and the Kurt Weill Centre in Dessau. Initiatives such as ‘Violins of Hope’, where violins from concentration camps and Jewish ghettos were displayed in the foyer of the Berlin Philharmonie (2015), the annotated reconstruction of the 1938 Düsseldorf exhibition ‘Degenerate Music’ (1988 and 2010) and ‘Verstummte Stimmen’ (Silenced voices, 2008), a travelling exhibition on the expulsion of Jews from Germany’s opera houses during the years 1933 to 1945, remain rare exceptions.

Musical instrument museums

As a rule, museums devoted to musicians are organised as independent entities. In contrast, most musical instrument collections form departments within larger institutions, whether these be universities, research institutes, state, regional or municipal museums, or museums focusing on technology, cultural history or the arts. Musical instrument museums can be distinguished by area of interest. Some take a comprehensive approach and display a broad spectrum of instruments from European and occasionally non-European music. Their task resides in preserving, cataloguing and expanding their collections, placing their holdings in he context of musical and cultural history, and examining and communicating the function, use and construction of musical instruments. Others are concerned exclusively with particular families of instruments (e.g. keyboard instruments, brass instruments or musical automata). They examine the technological evolution, manufacture and use of their particular group of instruments, often within the context of local history. For example, in 1930 a Museum of Violin Building was established in the town of Mittenwald, an historical centre of violin makers, to reflect the industry’s 300-year tradition within the history of the area. Today the Musical Instrument Museum in Markneukirchen deals in much the same way with the cultural history of the Vogtland region, known as Germany’s ‘music corner’. This museum, established as early as 1883 by the Markneukirchen Trade Association, originally had a quite practical purpose: being a ‘trade museum’, it provided local instrument makers with models for the manufacture of their instruments and visual aids for teachers at the trade school of instrument making, thereby ensuring that they kept abreast of international developments.

Though most of today’s noteworthy collections were in fact founded in the 19th century, the objects displayed in musical instrument museums often derive from private collections or from the holdings of former courts or aristocratic houses. The unique historical collections of instruments owned by the Wittelsbach dynasty in the 17th and 18th centuries, to choose but one example, entered the holdings of the Bavarian National Museum in Munich.

Among the ‘global players’ of musical instrument museums are those at Leipzig University, the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg and the Musical Instrument Museum in Berlin. The latter dates back to 1888, when a ‘collection of old musical instruments’ was established under the auspices of Joseph Joachim and Philipp Spitta in what was then known as the Royal Academic High School of Music. Its basic stock of 34 instruments from the holdings of the Prussian Chamber of Art was augmented in 1902 by two collections from the Leipzig publisher and music dealer Paul de Wit and the private collection of César Snoeck, a solicitor based in Ghent. At present the museum can boast of some 3,200 instruments related to art music of the 16th to 20th centuries. The Musical Instrument Museum of Leipzig University likewise stems from the collections of Paul de Wit. Today it has more than 9,000 objects illustrating the evolution of European musical instruments from the Renaissance to the present day, as well as mechanical instruments, historical sound recording devices, non-European musical instruments and an iconographical collection. The collections in both Berlin and Leipzig were originally designed for purposes of study at the local music school or university, respectively. To the present day they have pursued a scholarly approach that also encompasses such topics as historically informed performance practice and the history of interpretation. The Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg, founded in 1852, collected musical instruments from the very beginning, many of which came from the city’s churches. Today the collection primarily consists of European instruments of every type, with 3,000 objects ranging from the 16th to 20th centuries.

Other smaller collections, such as the Historical Keyboard Instrument Foundation of the Neumeyer-Junghans-Tracey Collection at Bad Krozingen Castle, have achieved national and even international stature owing to the exclusive nature of their holdings. As in many similar cases, the instruments were gathered together by private collectors.

From 2009 to 2011 nine European museums joined forces to work on the MIMO research project (Musical Instrument Museums Online) with the goal of making all the instruments in their collections accessible online. The German institutes involved in this project were the Musical Instrument Museum of Leipzig University, the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin’s State Museums. Today more than 65,000 objects can be examined on line. [1] Another joint research project is ‘MUSICES’, a guide to three-dimensional x-ray computer tomography of musical instruments, funded by the German Research Foundation and compiled from 2014 to 2018 by the Germanic National Museum and the Development Centre for X-Ray Technology at the Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits. [2] Among the applicants were the Musical Instrument Museum and the Ethnological Museum in Berlin and the Musical Instrument Museum of Leipzig University.

Several German colleges and universities have likewise established musical instrument collections for purposes of study. The facilities range from very large collections of historical instruments (e.g. the collection at the Department of Musicology of Göttingen University, with 1,700 European instruments from rural folk traditions and European art music) to musical instruments of the mod ern era. The collection at Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen also includes electronic, mechanical and electro-mechanical instruments from the synthesizer to the mixing desk. The Institute for Computer Music and Electronic Media (ICEM) at that same university is concerned with reconstructing the sound of electronic music, e.g. from the 1950s, for which the original equipment is indispensable.

Museums with an emphasis on regional music history

Some 20 regional museums in Germany display musical instruments and other musical items (often alongside other collections) in the context of local musical or cultural history. Among the many music centres that arose in Germany owing to its partition into myriad princedoms are the residential capitals of Sondershausen and Rudolstadt in Thuringia. By 1600 Sondershausen already had the earliest instrumentalists employed at a court. Beginning in 1617 Michael Praetorius established a court chapel there. The resultant Loh Orchestra numbered among the leading orchestras in 19th-century Germany, exercising a great influence on the successes of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt. Today the instruments of the former princely court chapel are found in the Castle Museum alongside a collection of 18th-century musical manuscripts. In the 19th century the emerging middle class es created centres of music outside the court environment. It was owing to these developments in cultural history that the City Museum in Braunschweig ac quired musical instruments formerly owned by the Brüderkirche and the Civil Guard. The importance of urban infrastructure for local musical culture is the theme of the Märkisches Museum of Berlin’s City Museum Foundation, which displays mechanical instruments as testaments to Berlin’s musical life between street music and middle-class parlours. Some museums at the state level contain not only instrument collections but also documents on the musical life and creativity in the region concerned, including sheet music, theatre playbills and concert programmes from various institutions.

Ethnological museums and collections

Musical instruments from non-European cultures are found primarily in ethnological museums. The objects in these collections are divided by large geographical region or continent or by universal aspects of life in various cultures, juxtaposed for purposes of comparison. As human culture becomes increasingly diverse, ethnological museums gain in significance, for they convey musical life in a wide range of cultures and preserve both tangible and intangible cultural her itage. Prime examples include the Rothenbaum Museum in Hamburg (known as the Museum of Ethnology until 2018) and the musical instrument collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne. Pride of place must go to the Ethnomusicology Division of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin’s State Museums, for it harbours the gramophone archive founded by Carl Stumpf and Erich von Hornbostel. This archive contains more than 150,000 recordings of non-European music and European folk music. With roughly 3,000 objects, it also preserves a large propor tion of the non-European musical instruments in Germany, to which must be added many further instruments in the collections of the Ethnological Museum’s regional branches. The scheduled removal of these collections to the newly reconstructed Berlin City Palace has kindled heated debates, for the sound archive contains recordings from prisoner-of-war camps and objects from Germany’s former colonies.

Other museums

One relatively new phenomenon in Germany’s museum landscape are museums devoted to popular music, combining the concept of a musician museum with ideas from cultural sociology. They also take into account that the origin and evolution of rock and pop music are inseparably connected with musical instruments, from the electric guitar to the Hammond organ and the Moog synthesizer. As one example, Gronau, the birthplace of the rock musician Udo Lindenberg, has created a museum devoted to the cultural history of 20th-century popular music.

Likewise outside the standard canon of museums are those devoted to music education. Rather than viewing themselves as institutions that collect, preserve , document and study objects, they focus on learning and experimentation for disabled and non-disabled children and young people. In the wake of music outreach programmes that aim to spread awareness of collections through hands-on experience, especially to young visitors, several music museums have emerged in Germany that allow visitors to try out various instruments with educational supervision. Berlin’s privately fund ed Sounding Museum (Klingendes Museum Berlin), for example, uses buses to visit schools, day-care centres and events. A similar approach is pursued by the Mobile Music Museum in Düsseldorf. The ‘learning and experimentation workshop’ musiculum in Kiel appeals to children and young people with school projects and courses that allow them to discover instruments, design sound objects or even produce their own songs.

Conservation and restoration

One challenge faced by all music museums is the proper conservation and presentation of their collections, which generally have an acoustic aspect that cannot be preserved and displayed like other artefacts or utilitarian objects. Musical instruments in museums are indeed used for making music, whether in concerts, during guided tours or for audio recordings. To this end they must be rendered playable, tuned, oiled, tended and cleaned. Museum objects should only be subjected to such treatment if it helps them to be perceived, appreciated and understood. Museums must constantly decide whether the changes made to an object are ethically permissible, especially in the case of musical instruments, where such changes may be irreversible. In recent years the field of restoration has become increasingly standardised and its training subjected to academic strictures. But owing to their heterogeneous organisational structures, not all museums have permanent staff for restoration work, and many must turn to traditional artisans and the free market.

Challenges of the digital age

Wherever visitors can turn to digitised versions instead of originals, documents and objects are protected. In consequence, recent years have seen important advances in the digitisation of documents and sources. Moreover, free access to scholarly information via the open-access presentation of digitised objects has captured the attention of the public

The Musical Instrument Museum of Leipzig University, for instance, has currently joined forces with the university’s Department of Image and Signal Processing in ‘TASTEN’, a digitisation project funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research to catalogue, acoustically digitise and photograph historical keyboard instruments in dimensional linear matrices. Its aim is to have access in future to machine-readable descriptive data, and not only to digitise the sonic repertoire but to reconstruct it through emulation. [3] The availability of research findings and exhibits on the internet is heavily dependent on the manner in which the institutions are financed, staffed and interlinked. Consequently, projects along these lines, especially in recent years, have been supported by the public sector (e.g. with funds from the German Research Foundation), the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, or by states, cities and municipalities. They also receive support from promotional associations and private donors. Digitisation projects are generally beyond the means of most museums unless they receive outside assistance.

Outreach programmes and museum education

Music museums increasingly view themselves not only as sites of documentation and conservation, but as active educational facilities. In museums devoted to musicians the focus of educational programmes falls on enlivening the life and work of the artist in question. Musical instrument collections increasingly place their exhibits in the context of musical and social history. For this reason practically all music museums offer special guided tours and programmes, especially for children and young people, acknowledging that cultural education works best when the museum’s visitors are actively engaged. The potential of new interactive technologies is being increasingly exploited. The Toccarion in Baden-Baden, for example, makes it possible for visitors to conduct a virtual orchestra, to play a ‘walking piano’ with their entire body or to construct rhythms on a ‘rhythm radar’ console.

Exhibitions in music museums can benefit from the possibilities of audio guides and/or ‘immersive’ sound installations in which the visitors themselves decide which work by a composer they want to hear, or which object they wish to learn more about. Some museums link their guides with object locations via wireless signals, so that visitors always hear information on precisely the objects they happen to be facing.

Video clips and computer animation can be used to illustrate complex acoustical processes, the intricate construction of an object, the importance of a composer to cultural history or the concert appearances of a particular performer. Today, how ever, such media are primarily employed interactively, as passive observa tion is seem ing ly undesirable to visitors and exhibitors alike. Here a balance must be struck between actionism and exploration.

Another means of conveying the research material of music museums lies in lecture-concerts that take into account the original sound of instruments and provide information on aspects of historical performance practice. Special exhibitions, catalogues, symposia, lectures and seminars, sometimes in conjunction with universities, research institutes or visitors’ academies, round off the out reach programmes of these facilities. Moreover, several museums hold performance competitions with the aim of introducing works by particular composers into the repertoire.

Music museums as tourist attractions

According to the Institute for Museum Research, in 2016 roughly half of Germany’s museums of cultural history were visited mainly by tourists. [4] Thus cultural tourism, in which guided city tours are offered to culturally minded visitors, has recently become a major area of activity for museums. The focus increasingly tends to fall on collaborations with the tourist trade industry, the improvement of local infrastructure (public transport, signposting, restaurants, cafés), the adjustment of opening hours, an emphasis on service, multilingual supervisory staff and accessibility for disabled people. Many visitors show particularly great interest in programmes, concerts or workshops tailored for children. Even such mundane things as the presence of a gift shop can be decisive for the number of visitors to a museum. Here it is crucial to pinpoint the institution’s strengths and weaknesses with visitor surveys and evaluations and to develop appropriate improvements.

Associations

A number of associations represent the interests of museums on the national and international level. The German Federation of Museums is the nationwide association for all museums in Germany. The Institute for Museum Research in Berlin’s Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation) is a nationwide research and documentation facility that represents the concerns of the Foundation, the federal government and the German states within a panEuropean context. The German Musicological Society has a special chapter for the study of musical instruments that functions as a forum and clearinghouse for information regarding instrument collections attached to research institutes and universities. The working group ‘Music Museums in Germany’ represents a number of important establishments devoted to preserving the legacy of outstanding composers and artists.

. On an international level, museums are organised in the International Council of Museums (ICOM), which is devoted to the cause of conserving, cultivating and communicating the world’s cultural heritage. Its internationally valid Code of Ethics for Museums calls for a documentation of museum collections ‘in accordance with generally recognised professional standards’. The ICOM works in many specialised commissions and committees, with music museums being organised in the CIMCIM (Comité international pour les musées et collections d’instruments et de musique).

Prospects for the future

The tasks of music museums have changed remarkably in recent years and under gone considerable expansion. The traditional duties of collecting, preserving, communicating have become more transparent, and more complex, owing to the modern demands placed on cataloguing, documentation, site administration and provenance research. At the same time conservation and restoration are becoming increasingly standardised, professionalised and placed on a more scholarly basis.

Influenced by Anglo-American models, museum education in Germany is undergoing a transformation that places the main focus on visitors and their active role in the museum. Many museums have realised that a museum’s theme and contents, the architecture of its building, its interior décor and the design of its exhibitions are of crucial importance to its attractiveness. Expressions of this transformation include the widespread remodelling and new construction of museum buildings, fresh ideas for permanent displays and appealing special exhibitions and updated websites and databases.

Given that these institutions are sustained by the federal government, states, communities, foundations, associations and private individuals, the financing of museums is extremely complex. As a result, many museums face an uncertain future, as reflected not only in staff shortages and inflexible opening hours, but in the hiring of museum educators, consistent outreach work, appropriate conservation and sustained research on their holdings. Which paths individual museums choose to follow in order to cope with these problems is heavily dependent not least on the circumstances in their particular region or locality

Footnotes

See ‘MIMO – musical instrument museums online’ at https://www.hugedomains.com/domain_profile.cfm?d=mimointernational.com (accessed on 14 September 2018).

See the project description at https://gepris.dfg.de/gepris/projekt/248476191 (accessed on 14 September 2018).

See the project description at https://mfm.uni-leipzig.de/dt/Forschung/%20Tastenprojekt.php (accessed on 24 September 2018).

See Institut für Museumsforschung, ed., Statistische Gesamterhebung an den Museen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland für das Jahr 2016 (Berlin, 2017), p. 31; online at https://www.smb.museum/fileadmin/website/Institute/Institut_ fuer_Museumsforschung/Publikationen/Materialien/mat71.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2018). The total number of visits to special museums of cultural history in 2016 was approximately 11 million, or roughly 10 per cent of all museum visits in Germany (ibid., p. 27).