Memory institutions, such as music libraries, archives and museums, are a sine qua non for the study and performance of music. These facilities, which preserve and transmit rich bodies of knowledge, are primarily found in the public sector. They have a great many tasks, some of which overlap or interrelate. Traditionally, they collect and catalogue source material, literature, sheet music, sound recordings, audio-visual media, musical instruments and – especially in museums – objects related to musical life. However, thanks to the digital revolution, for several years they have also preserved non-physical formats such as digitisations of their own physical holdings, including files of music, musical notation, e-mails and texts (e.g. from posthumous estates). Equally new is their function as aggregators, for example for streaming services. At present, Germany’s libraries must respond to changes in information infrastructure and the prospect of setting up a National Research Data Infrastructure (Nationale Forschungsdateninfrastruktur, or NFDI) – a project discussed by Germany’s states and federal government. [1] All of this naturally affects those institutions concerned with and actively involved in music information and documentation, whether owing to the research data they themselves collect or to their responsibility for providing long-term access to findings from universities and other research bodies. This is accompanied by upheavals in key activities and professions. After all, libraries face a new challenge: even relatively new types of research data must likewise be collected, stored and made accessible. This influences the way that libraries work, forcing them to change and expand their modes of operation. As a result, libraries and their fields of activity are currently undergoing a major transformation.

Libraries concerned with music information and documentation basically fall into two types: public music libraries (or general public libraries with music collections), and scholarly music libraries (or music departments in scholarly libraries). In addition to libraries at musical institutes of higher learning (Musikhochschulen), broadcasting companies and orchestras, the range also includes specialist libraries that maintain musical holdings, such as libraries at music research institutes or the musicology departments of universities.

The world of archives also has institutions with extensive musical holdings, such as those associated with broadcasters, art academies or music publishers. There also exist specialist archives devoted to particular composers, sometimes with adjoining museums (see Heike Fricke’s essay ‘Music Museums and Musical Instrument Collections’). State and regional archives also preserve material on music history and cultural life, including, for example, the records of court theatres or collections of programme leaflets.

Many of these institutions are members of the German chapter of the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML). With 215 members, this national branch is one of the largest within the IAML. Founded in Paris in 1951, IAML maintains three official languages – English, French and German – and has 26 national branches throughout the world. Every year it holds an international congress at a different location. There is also a national congress in Germany, likewise held at different locations. The German chapter of IAML publishes the periodical Forum Musikbibliothek [2], complementing IAML’s periodical Fontes Artis Musicae [3] on the international level.

As befits its political subdivision into federal states, each with independence in cultural matters, Germany has no publicly owned central institution that collects (unpublished) musical sources, as the German Literature Archive in Marbach does for German literature. Holdings of individual institutions are mainly collected and enlarged by provenance, though historically established points of emphasis naturally play a role. Some libraries and archives with a musical focus also take charge of interstate or even nationwide assignments.

‘Public libraries have played an important role as a so-called ‘third place’, a gathering spot or living space with special opportunities for exchanges and encounters.’

Public music libraries

The task of public music libraries, or public libraries with a music department, resides in offering a wide assortment of sheet music, books on music, musical periodicals, sound recordings and audio-visual media from every area of music, whether for use on location or for taking out on loan. They also help by providing specialist information and supporting research. Recently public libraries have played an important role as a so-called ‘third place’, a gathering spot or living space with special opportunities for exchanges and encounters. Depending on the size of the library, the spectrum may also include scholarly editions, special reference works and research literature. Generally the offerings are freely accessible and mainly serve the purposes of practical music life, sometimes even including practice rooms. The libraries also place great stock in public relations by organising concerts, lectures and exhibitions on the subject of music. No less important is their role as a place of learning and a meeting place for practically all age groups – as sites of information exchange for professional musicians, schools and the world of musical performance altogether. [4]

Large public libraries also preserve historical collections. A good example is the Central and Regional Library in Berlin (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek), where, among other things, visitors may use a collection of more than 73,000 LPs representing the output of sound recordings in the former state of East Germany. One of the largest of Germany’s public music libraries is found in the Munich City Library (Münchner Stadtbibliothek Am Gasteig), with 52,000 books, 70 periodical subscriptions, 122,000 items of sheet music and 67,000 sound recordings, plus special collections of rare items and autographs. Other large public music libraries are located in Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg, Dresden, Leipzig, Düsseldorf, Stuttgart and the district libraries in Berlin.

Scholarly music libraries

The classical tasks of scholarly libraries – collection, acquisition, cataloguing, utilisation and presentation – also apply in general to their music departments. [5] Source material and research literature are indispensible for the practice of musicology, and they must be kept ready to hand with maximum completeness. In Germany, unlike Europe’s more centralised states, this task is spread among various institutions. It was not until 1912 that a German national library was founded in Leipzig (Deutsche Bücherei). Its mandate covered all literature published domestically, whether in German or in foreign languages, and all German-language literature published abroad. Only in 1943 was its mandate expanded to include sheet music. Following the partition of Germany, the German Music Archive (Deutsches Musikarchiv, or DMA), located in what was then West Germany, only began to archive depository copies of sheet music in 1973. The nationwide collection of sound recordings in West Germany came equally late, beginning only in 1970. After the reunification of Germany in 1990, the Deutsche Bücherei in Leipzig and the Deutsche Bibliothek in Frankfurt am Main (founded in West Germany in 1947) were merged into a single national library under the name Die Deutsche Bibliothek (known since 2006 as Deutsche Nationalbibliothek). The German Music Archive (DMA), initially headquartered in Berlin, relocated to Leipzig in 2010. A new legal mandate of 2006 gave the DMA, in addition to sheet music and sound recordings, the obligation to collect and catalogue music publications in the Web (audio files and digitised sheet music). Because of this convoluted history, there still exist gaps, especially in the systematic collection of all sheet music printed in Germany. This gap was and is meant to be closed by a consortium of scholarly libraries known as Collection of German Prints (Sammlung Deutscher Drucke, or SDD). Founded in 1989, it is tasked with the retroactive collection and cataloguing of literature, sheet music and maps up to the year 1912. The acquisition of printed music is shared by the Bavarian State Library in Munich (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, or BSB) up to the year 1800, and the Berlin State Library (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, or SBB) from 1801 to 1945.

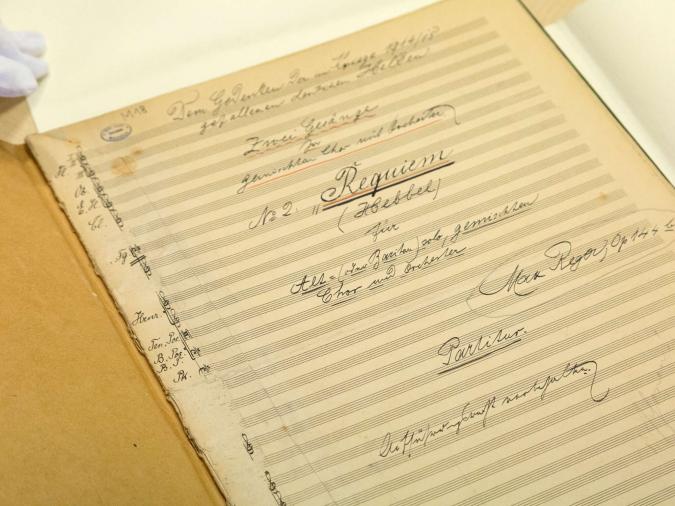

For historical reasons, the great state, regional and university libraries have music departments with antiquarian holdings (manuscripts, music prints, librettos, posthumous estates and bodies of correspondence). Today they also collect writings on music, sheet music (complete scholarly editions as well as performing editions) and sound recordings. Among the largest music departments or collections are those of the state libraries in Berlin and Munich. Important music departments are also found at the Saxon State and University Library in Dresden (Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden) and in Coburg, Darmstadt, Detmold, Frankfurt am Main, Karlsruhe, Münster, Schwerin, Speyer, Stuttgart, Wolfenbüttel and Hamburg. Similar tasks in research and scholarship are carried out by the libraries of musicological institutes and the specialist libraries of such research and publishing bodies as the Bach Archive in Leipzig, the Beethoven House in Bonn, the Joseph Haydn Institute in Cologne and the Max Reger Institute in Karlsruhe.

Conservatory libraries

Germany is noted for its wealth of tertiary-level conservatories (Musikhochschulen). All of them maintain libraries to serve their own students and teaching staff. At present, the Conference of Rectors of German Conservatories unites 24 institutions with libraries primarily open to their own members, focusing mainly on study and performance material. Some of them also preserve historical collections.

Broadcasting and orchestral libraries and archives

Germany’s broadcasting and orchestral libraries are open only to employees of the relevant broadcasting corporation or to members of the concert or opera orchestra concerned. Access to the archives of Germany’s public broadcasters by scholars and researchers was uniformly regulated in 2014. The German Broadcasting Archive (Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv, or DRA), a non-profit foundation of Germany’s First Broadcasting System (ARD) and Deutschlandradio, is also open to outsiders. One of the country’s largest media archives, the DRA houses large collections of audio and video recordings, written materials, publications and documents. The audio-visual holdings date back to the beginning of sound and video recording, thereby documenting the evolution of broadcasting in Germany. Major points of emphasis include radio broadcasting up to 1945 and radio and television broadcasting in the former state of East Germany.

Music archives

Music archives can be found in private and public ownership with a very wide variety of holdings. They range from the privately funded jazz-related Lippmann+Rau Archive in Eisenach to the archive of the International Music Institute in Darmstadt (IMD), an information centre on post-1946 contemporary music in Germany and abroad, to the German Archive of Folk Song (Deutsches Volksliedarchiv) in Freiburg im Breisgau, which has been integrated in the Centre of Popular Culture and Music at Freiburg University since 2014. An equally highly specialised facility is the music archive of the Academy of Arts in Berlin (Akademie der Künste), which preserves posthumous estates and working archives related to contemporary music of the 20th and 21st centuries, mainly by the Academy’s own members and master-class pupils. There are also archival holdings from large music publishing firms such as Schott, Breitkopf & Härtel and Peters; some are located in the firms’ present premises, others in public institutions such as archives, libraries and research centres.

Music information and documentation centres

Independently of local music documentation centres, the German Music Information Centre (Deutsches Musikinformationszentrum, or miz), a central clearing house for information on musical life in Germany, supports various groups of users. It has large collections of data on the central areas of musical life, including structural data on more than 10,000 institutions, large collections of statistics and specialist articles on individual topics, all with the aim of documenting and communicating the structure and evolution of Germany’s musical culture. A publicly funded facility, the miz updates its information on a regular basis and systematically prepares it for research purposes under many headings. The miz is linked with related partner organisations all over the world.

Comprehensive access to source collections, information on holdings, and materials for music and musicology are offered by the specialised information service for musicology (= ‘musiconn - for networked musicology’) [6]. ‘Musiconn’ is the brand name of the project “Fachinformationsdienst Musikwissenschaft” funded by the German Research Foundation. It is a central information portal for music and musicology and, in addition to electronic collection development including provision and long-term archiving, offers extensive and fast access to academic research as well as to a wide range of specialised information and internet resources with specific research options and search access points.

For licensing reasons, members of the Gesellschaft für Musikforschung (GfM) and the Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie (GMTH) who are resident in Germany have free access to fee-based services. Individuals without a connection to the GfM or GMTH can register via the Bavarian State Library, stating a research interest. Due to the contractual requirements of the licence partners, a residence in Germany is generally required for all registrations. In addition, members of research institutes based abroad but funded by public institutions in Germany have the option of registering with the respective German address of the funding organisation.

One important recent development is the project ZenMEM (Zentrum Musik – Edition – Medien), of Paderborn University, which brings together the university`s activities in the field of digital music editing and digital musicology. It is the successor to the Edirom project, which developed tools for digital forms of scholarly-critical music editing, and is home to the Edirom Virtual Research Network, an association of academics working on the conceptual and technical development of digital musicology. [7]

The above-named International Association of Music Libraries (IAML) and the International Musicological Society (IMS) are jointly responsible for several vital research-related projects. One is Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM). Founded in 1952 and now headquartered in Frankfurt am Main, it references sources on music ranging from pre-1800 music prints, post-1600 music manuscripts, sources on music theory, and Arabic, Greek, Hebrew and Persian sources. This transnational non-profit organisation is funded primarily by Germany via the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities. [8] Musicologists and performers have at their disposal, free of charge, the RISM-OPAC of the BSB in Munich, with a database hosted by the SBB in Berlin. In addition, since 1971 RIdIM (Répertoire International d’Iconographie Musicale) has been documenting visual material related to music, principally in the visual arts and handicrafts. [9] RILM (Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale), headquartered in New York, has been listing writings on music, such as monographs and essays, since 1967. [10] This international bibliography with roughly one million entries on scholarly studies of music also provides abstracts. Information for the German area of RILM is supplied by the database ‘Bibliographie des Musikschrifttums online’, offered free of charge by the SIM in Berlin and now boasting more than 360,000 entries. [11] The fourth of the so-called ‘R’ projects is RIPM (Répertoire International de la presse Musicale), which has, since 1980, listed music-related articles and illustrations from rare primary-source music periodicals from the 18th to 20th centuries. [12]

Training and advanced education

As most German libraries are financed by the public sector, library services are mainly structured in accordance with the conditions underlying the civil service. As a result, there are higher and mid-level civil servants employed at scholarly and public libraries. [13] The prerequisite for access to higher-level civil service is a degree in musicology followed by an internship or post-graduate training. [14] Studies for entering higher-level service at scholarly or public libraries are offered with various degrees by technical colleges inter alia in Hanover, Leipzig, Potsdam and Stuttgart. Courses related to music librarianship can be taken as part of degree programmes in information and media studies. [15] The prerequisite for a three-year training programme for employment in the media and information services, or for mid-level library service, is the mittlere Reife, a secondary school leaving certificate roughly equivalent to the O levels in Great Britain. The training programme is general in nature without a special emphasis on music.

Owing to the digital revolution, the occupational profile has changed so markedly that course material must be adapted at ever-shorter intervals. Curricula now cover such topics as Strategies in the Semantic Web, Digital Archiving and Acquisition and Processing of Online Media. The current technological and economic upheavals are causing knowledge to become ever-more rapidly obsolete, with the result that advanced training in information and documentation is now de rigueur.

Current developments

The origin and operation of musiconn, the on-going transformation of collections relevant to musical performance and research into online repositories, the generation of research data in digital editions, the national initiative for the organisation and use of research data NFDI, the publication of e-media, the digital publication of audible music via downloads or streaming: all of these are symptoms of a ‘change of paradigms in archiving’, [16] as are the specific demands they place on data modelling and retrieval systems, algorithmic analytical methods, text mining, optical character and optical music recognition, and disciplinary and interdisciplinary contextualisation through linked (open) data. [17]

‘Digital’ is not just another term for ‘electronic’; it is ‘an episteme, and thus an order of knowledge all its own’. [18] In any event, it changes the millennia-old function of libraries and archives as memory institutions pure and simple. The growing presence of the digital, the increasing number of digital originals (‘digital born’) and the associated specific nature of encoded information (as opposed to historically generated knowledge) have brought about a seismic shift in the way we perceive search results, modes of access and ultimately the conditions of reception.

The classical library was a site that reinforced the continuum known as historical memory, which could be monumentally safeguarded between the covers of a book or durably conserved on sound and video recordings. In contrast, a digital library generated from linked data files can be used without references to history or cognitive references generated by librarians or archival administrators. As a result, a mandatory and historically legitimised ontology has become obsolete. The digital creates an ‘an-historical’ reality in a virtual universe. In principle, anything can be linked with anything else.

In the electronic library the traditional static catalogue gives way to dynamic search engines and discovery systems.

Before the information landscape was universally digitised, and thus until well into the 1990s, specialist searches were usually limited to library catalogues and a few specialist databases. Today, in contrast, researchers have at their disposal a virtually limitless multitude of digital information resources and search tools, from the discovery system to specialist databases and portals to technical and institutional repositories and scholarly search engines. In particular, the wide-ranging and constantly expanding digital collections present in the internet, whether generated in accordance with the standards of librarianship (as in the Digital Collections of the Library of Congress [19] ) or based on private initiatives (as in the IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library [20] ), with a correspondingly ‘free’ and less regulated structure, all demand contextualisation and visualisation ‘on diverse platforms and portals in the internet, such as institutional websites, regional culture portals, the German Digital Library, Europeana or Archivportal-D’ or musiconn. [21]

Admittedly, extant analog systems that guide users to a library’s holdings, making them systematised and accessible, are not yet obsolete. Many conventional card catalogues with references to special holdings have yet to be converted. [22] But this will happen with the passage of time and the growth of digitisation, which inevitably entails a conversion of metadata or even a new cataloguing system. Extant CD-ROM databases, and especially internet sources such as net publications and e-media of every type (e-books, e-journals, databases), must be sorted and archived as information with proof of their relevance to the subject at hand. Research data in the humanities is usually ‘digital representation and processing forms of cultural objects which ought, in principle, to be presented in the same way as in traditional archives and libraries’. [23] The digital transformation of research itself, and of its publication, thus requires ‘not less but more preparation and saving of content’, meaning in this case research data. [24]

Digital research data can be ‘both the origin and the result of scholarly work’ and is ‘documented in regulated and machine-readable form, catalogued in accordance with international standards (ideally) and marked with authority data, making it amenable to both processing and interpretation’. [25] The many digital and hybrid publishing projects in German-language musicology, which generate such research data using music and text encoding (e.g. in the Edirom Virtual Research Group [26] ), must ensure that the data is securely stored and reusable once the project concerned has come to an end. [27]

Thus, in recent years even the ‘classical’ work of specialist librarians has markedly changed. Where it was once purely a matter of acquisition and cataloguing, it has now expanded into multilevel activities. The librarian is now a conduit and, at the same time, an agent of ‘knowledge management’ in dialogue with specialist fields and information technology (‘embedded librarianship’). The demands placed on librarians with regard to specialist expertise have grown accordingly. This affects questions regarding information technology, the ordering and organisation of knowledge in the ‘ecosystem of contextualised and networked data collections’, [28] strategies for long-term archiving and utilisation, and questions of licensing and rights management that arise especially when holdings are presented online and reused.

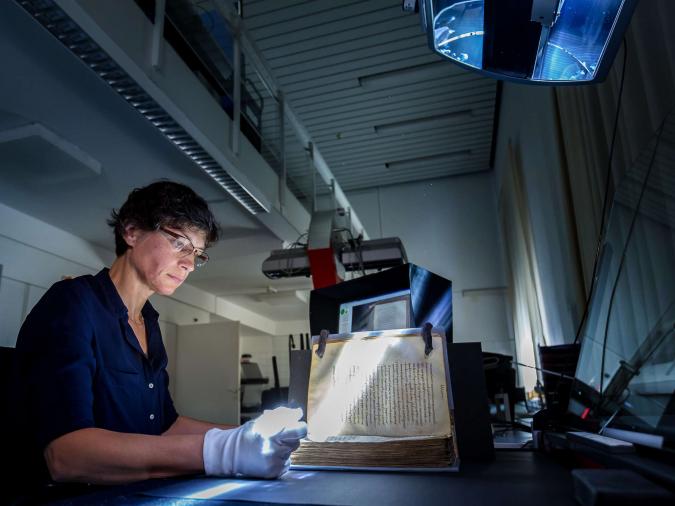

In this light, recent years have witnessed the birth of a number of innovative library service concepts that offer scholars support and cooperation in dealing with digital data, documents, tools and infrastructures in their research and teaching. At the Bavarian State Library, for instance, these include the International Image Interoperability Framework project (IIIF) [29] , which sets new standards for presenting digital images and data in the internet. Similarly DaFo (Daten für die Forschung), the internationally accessible free downloading service for high-resolution images and their associated texts (if already machine-readable); the possibility of image-based similarity searches [30] ; and the development of application scenarios for Optical Music Recognition (OMR) in the musicological information service Musiconn [31] : all offer novel opportunities in the scholarly study of music and related fields of research.

The specific demand placed on data modelling – authority data, music and text encoding (MEI [32] , TEI [33] ), protocols, documentations, decisions on formats and standards and so forth – already necessitates an appropriate workflow and efficient and proactive resource management in the course of scholarly research, and not just in the context of a library’s collection activities. It is thus essential to establish, at an early stage, a close-knit cooperation when developing projects between scholarship and information infrastructure facilities.

The boundaries between archives, libraries and research were thus redrawn long ago. A cautious glimpse into the future also suggests that the traditional activities of librarianship will become less and less important, for ‘the future task of the library as knowledge infrastructure’ will chiefly be ‘to curate the basically infinite linked open data space’ [34] – a service defined primarily by technology. The related sustainable responsibility for resources is, of course, a ‘very strong performance promise’ for every humanities research library, because ‘the permanent power of disposal over the information resources is the decisive prerequisite not only for ensuring the [...] explorative working environment, but also for the services that serve to contextualise the content held. The human and financial resource demands of collecting is even increased in the digital world, as the total costs of all services subsumed under the term ‘data curation’ often exceed the costs of storing and preserving printed collections many times over.’ [35]

Footnotes

See RfII – Rat für Informationsinfrastrukturen: Leistung aus Vielfalt. Empfehlungen zu Strukturen, Prozessen und Finanzierung des Forschungsdatenmanagements in Deutschland (Göttingen, 2016), online at http://www.rfii.de/download/rfii-empfehlungen-2016 (accessed on 28. June 2024).

Forum Musikbibliothek: Beiträge und Informationen aus der musikbibliothekarischen Praxis (Weimar, 1978-99; Berlin, 2000- ), ed. by the German chapter of IAML. Available online from 2012 at http://www.aibm.info/publikationen/forum-musikbibliothek (accessed on 28. June 2024).

Fontes Artis Musicae, ed. International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) 1954ff.

See the article ‘Öffentliche Musikbibliotheken’ by Verena Funtenberger, 2018. Online at https://miz.org/de/beitraege/oeffentliche-musikbibliotheken (accessed on 2. October 2024).

Martina Rebmann, ‘Musikabteilungen in wissenschaftlichen Bibliotheken. Aktueller Stand: Kooperationen, Projekte, Perspektiven’, Musikbibliotheken – Neue Wege und Perspektiven, special issue of Zeitschrift für Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie (ZfBB), ed. Michael Fernau, Reiner Nägele and Martina Rebmann, vol. 59 (2012), pp. 129-36.

Musiconn – für vernetzte Musikwissenschaft. Portal of the Specialized Information Service for Musicology, online at https://www.musiconn.de/en/ (accessed on 1. October 2024).

See ZenMEM, Über uns, online athttps://zenmem.upb.de/about (accessed on 23. August 2024). The ZenMEM project emerged from a BMBF-funded project of the same name, which ran from 2014 to 2019 as a joint project between Paderborn University, Detmold University of Music and Ostwestfalen-Lippe University of Applied Sciences. The aim of the centre was to promote the use of digital methods, build up corresponding resources and develop suitable tools. See ZenMEM, Das Zentrum, Projektbeschreibung, online at: https://project.zenmem.de (accessed on 23. August 2024).

See https://rism.info/community.html (accessed on 1. October 2024).

Répertoire International d’Iconographie Musicale, online at https://ridim.org (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale, online at https://www.rilm.org (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung Preußischer Kulturbesitz: Bibliographie des Musikschrifttums online, online at https://www.musikbibliographie.de (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Répertoire international de la presse musicale, online at: https://www.ripm.org (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Information can be found in the internet on the home pages of technical colleges and hiring institutions, e.g. at https://staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/extras/spezielle-interessen/ausbildung (accessed on 2. October 2024).

Further information inter alia at http://staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/extras/spezielle-interessen/ausbildung/referendariat/; https://www.ibi.hu-berlin.de/en/teaching/study-programs/study-programs and https://bibliotheksportal.de/informationen/beruf/berufswege/wissenschaftlicher-dienst(accessed on 26 June 2024).

Information on course offerings at https://bibliotheksportal.de/informationen/beruf/berufswege/studium (accessed on 26 June 2024).

Aleida Assmann, quoted from Alexander Roesler and Bernd Stiegler, eds., Grundbegriffe der Medientheorie (Paderborn, 2005), p. 25.

On the standard technologies and technical terms see Fotis Jannidis et al., eds., Digital humanities: Eine Einführung (Stuttgart, 2017).

Hanna Engelmeier: ‘Was ist die Literatur in “Digitale Literatur”’, Merkur 71 (2017), pp. 31–45, quote on p. 32.

Library of Congress: Digital Collections, online at https://www.loc.gov/collections/ (accessed on 9. September 2024).

International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) / Petrucci Music Library, online at https://imslp.org/ (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Klaus Ceynowa: ‘Vom Wert des Sammelns und vom Mehrwert des Digitalen – Verstreute Bemerkungen zur gegenwärtigen Lage der Bibliothek’, Bibliothek – Forschung und Praxis, 39 (2015), pp. 268-76, quote on p. 273.

For example, the card catalogue with references to more than 300,000 printed music works from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin has been converted since the beginning of 2023, a project that will probably be completed in 10 years, see https://blog.sbb.berlin/start-der-konversion-der-zettelkataloge-fuer-noten-und-musikbuecher-der-musikabteilung/ (accessed on 26. Juni 2024).

Position paper of the German Association of Historians (VHD) on the creation of a nationwide research data infrastructure at https://www.bundesarchiv.de/DE/Content/Downloads/KLA/positionspapier-forschungsdateninfrastruktur.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 26. June 2024).

Elmar Mittler: ‘Wohin geht die Reise? – Bibliothekspolitik am Anfang des 21. Jahrhunderts’, Bibliothek – Forschung und Praxis, 41 (2017), pp. 213-23, quote on p. 219.

Jenny Oltersdorf and Stefan Schmunk: ‘Von Forschungsdaten und wissenschaftlichen Sammlungen: Zur Arbeit des Stakeholdergremiums “Wissenschaftliche Sammlungen” in DARIAH-DE’, Bibliothek – Forschung und Praxis, 40 (2016), pp. 179-85, quote on p. 182.

Musikwissenschaftliches Seminar Detmold/Paderborn: ViFE – Virtueller Forschungsverbund Edirom, online at https://www.edirom.de/projects.html (accessed on 9. September 2024).

See ‘Grundsätze zum Umgang mit Forschungsdaten der Allianz der deutschen Wissenschaftsorganisationen’, ratified on 24 June 2010, available at https://www.konsortswd.de/wp-content/uploads/RatSWD_WP_156.pdf (accessed on 26. June 2024).

Mittler, ‘Wohin geht die Reise?’ (see note 16), p. 217.

Global consortium forms to standardize and improve sharing and displaying of image-based scholarly resources on the web, online at https://www.bsb-muenchen.de/fileadmin/pdf/presse/2015/IIIF_release.pdf/ (accessed on 1. October 2024).

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek: Image-based Similarity Search online at https://bildsuche.digitale-sammlungen.de/ (accessed on 2. October 2024).

Musiconn: Scoresearch, online at https://scoresearch.musiconn.de/ScoreSearch/?lang=en (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur Mainz: Music Encoding Initiative, online at https://music-encoding.org/ (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Text Encoding Initiative, online at https://tei-c.org/ (accessed on 9. September 2024).

Klaus Ceynowa and Lilian Landes: ‘Neuer Wein in neuen Schläuchen: Von Wissenschaftlern, die nicht nur anders publizieren, sondern auch anders schreiben werden’, Bibliothek – Forschung und Praxis, 38 (2014), pp. 287-93, quote on p. 292.

Klaus Ceynowa, Research Library Reloaded? Überlegungen zur Zukunft der geisteswissenschaftlichen Forschungsbibliothek, in ZfBB 65 1/2018, pp. 3-7, quote on p. 7.