Germany in the 19th century was equally inclined toward progress and restoration, which made it an ideal breeding ground for festivals. At the same time that Wagner was concocting his festival scheme, George II, the Duke of SaxeMeiningen, as director of his own court theatre, developed the notion of ‘model performances’ for classical drama. He focused on Shakespeare’s plays, which he popularised in guest performances all over Europe.

Franz Liszt inaugurated the Beethoven Festival (Beethovenfeste) as early as 1845 to accompany the unveiling of the Beethoven Monument on Bonn’s Münsterplatz. Admittedly it only received its permanent structure and regular annual cycle decades later, when it merged with the ‘Folk Beethoven Festival’ (Volkstümliche Beet hoven-Feste), founded by Elly Ney in 1931. Two years after Liszt, the Danish composer Niels Wilhelm Gade established the first music festival for Robert Schumann in Zwickau, which was made a permanent institution in 1860 to honour the composer’s 50th birthday. And the earliest festival of orchestral music, the Music Festival of the Lower Rhine (Niederrheinische Musikfeste), was held in various Rhenish cities at Whitsuntide every year beginning in 1817.

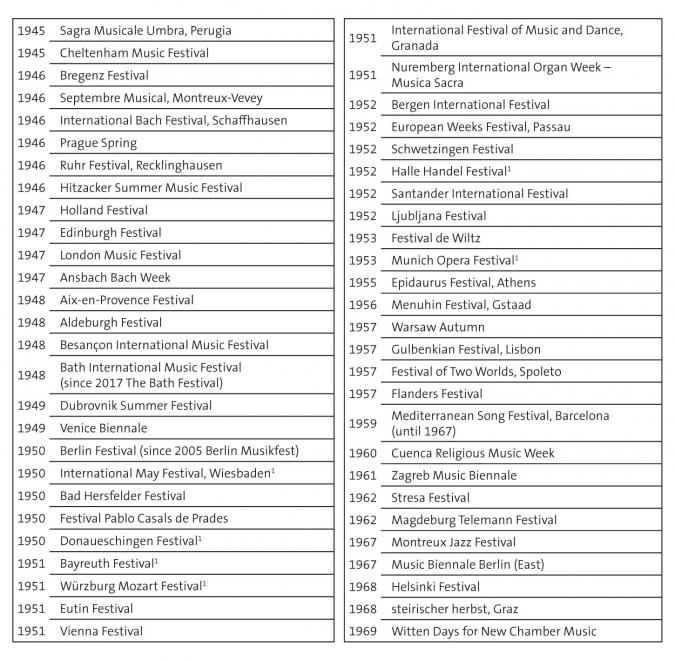

Since the mid-20th century this historical form of Festspiele with its lofty artistic standards – and many today would say its air of elitism – has competed with a more recent type of event unburdened by tradition: the Festival. It tends to target a mass audience, aligns its programmes not least on marketing strategies and views the ‘event’ in itself as the main vehicle for its success. This new term only entered German vocabulary after 1945 as the influence of America made itself felt on the ‘Old World’. Like the term itself, this form of festival stems from the Anglo-Saxon countries. Indeed, the first festivals arose in England after the Second World War: the Cheltenham Music Festival in 1945, the Edinburgh Festival and the London Music Festival in 1947, and the Aldeburgh Festival, founded by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears in 1948 (see Fig. 1). They were followed by a wave of newly founded festivals, from the Holland Festival (1947) to the Montreux Jazz Festival (1967). All sought to set themselves apart from the old-fashioned élite festivals in their conception, target groups, marketing strategies and, not least, their programmes. That popular music of every shade and hue – from jazz to rock, pop and beat all the way to heavy metal and electronic folk – has found its ideal mode of presentation in festivals is now an established fact.

Yet it is often forgotten that the term ‘festival’ originally entered German to distinguish the new, open-minded, ‘democratic’ type of event from its predecessor, the Festspiel. Even old-style Festspiele have long taken to calling themselves ‘Festivals’; indeed, given the globalisation of the arts industry, this was virtually unavoidable. Meanwhile, in our age of event culture, everything is called a ‘festival’ that is held in public over a limited time span and enters the turmoil of competing markets and media. Consequently, the terms definitely stand in need of clarification.

Definitions

There is no unequivocal definition of the concepts of Festspiel and festival. To quote Harald Kaufmann, ‘Celebrations and festivities are not a proper subject for a neutral sociology of knowledge’. [1] Rather, they are influenced by subjective judgments depending on the historical standpoint, personal interests and ideological biases of the observer. Therefore, the only way to determine the defining features of these two phenomena in our cultural life is empirically, by describing their characteristics and comparing them with related phenomena.

Riemann Musiklexikon, the standard music dictionary in German, defines Festspiel as follows: ‘Festspiele and Musikfeste are events that are meant to present performances of superior quality or with forces unavailable in normal repertory conditions. They are also lifted out of the ordinary by their choice of venue, which is distinguished by tradition, by special buildings and a holiday-like atmosphere, and by the commissioning of new works of music’. [2] A more detailed definition is provided by the relevant entry in Metzler’s Musiklexikon, which begins as follows: ‘Festspiele, Musikfeste (Eng. and Fr.: ‘festivals’): musical events extending over several days or weeks, usually recurring at regular intervals and held at the same loca tion every time. By their specific programming policy and their choice of renowned artists, they are meant to present exemplary performances of concert music and/or works of music theatre. Their choice of location is often determined by the musical tradition of that location, but also by the special atmosphere of its architecture and landscape’. [3]

Festspiele emerged between the 17th and 19th centuries from court festivities and historicising anniversary celebrations (Handel’s centenary in 1785, Mozart’s in 1856) and were adopted by the burgeoning middle classes as tools for their emancipation. But it was not until after World War II that this type of event became a determining factor of our musical life. As the new species of festival made greater inroads and took stronger hold, the festival mutated from an art form, traditionally viewed as a supreme cultural achievement, into an organisational form dominated by our industrial society’s ideal of perfection. Festivals, in other words, also express the zeitgeist in which they take place. Their event character, their strategies for marketing ‘sensational’ artists or artistic achievements and, not least of all, their position in the media: all turned festivals into a seminal form of artistic activity with future potential.

It is striking how quickly the ‘new’ post-war festivals (Venice, Berlin, Vienna, Athens) learned to capitalise on the virtues of European unification: tight-knit networking of information, unrestricted exchange of artists and productions, rapid media exploitation and ‘political correctness’. All of this has almost ineluctably merged with a sharp focus on current fashions, an occasionally imprudent adherence to the zeitgeist, and often an abject deference to box-office hits. There are, of course, exceptions. Some festivals proclaim their opposition to prevailing opinions and currents, finding niches for the little-known or the disconcerting (e.g. very early and very new music). Others refuse, at least partly and temporarily, to join the merry-go-round of global cultural marketing. But all in all, the new species of festival is increasingly blotting out the traditional institutions of bourgeois culture from public awareness. ‘Festivals’, Karin Peschel wrote in her final report on the economic impact of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival (1998), ‘are becoming a mainstay of our musicocultural offerings, augmenting the traditional opera and concert seasons’ [4] – and, we should add, replacing them with ever-increasing frequency.

Criteria

The lasting value and perhaps even the raison d’être of Festspiele and festivals alike are governed by four criteria:

- an outstanding programme,

- exemplary performances,

- exceptional modes of presentation and

- a distinctive idea and/or atmosphere.

In an age when the culture industry is increasingly governed by the global marketing of top stars, the ubiquitous dissemination of artists and programmes as ‘brand-name items’ and the total availability of information, there is no question that exemplary performances and exceptional modes of presentation have become key criteria of any serious festival strategy.

An outstanding programme refers not only to the presentation of the pro gramme per se, but in particular to the artistic offerings and the manner in which they are turned into events. A festival stands out from year-round opera houses and concert halls in three ways: artistically, organisationally and socially. Among the distinguishing organisational features of a festival are a predefined and regularly recurring time slot, a special location, and an avoidance of fixed modes of operation in favour of ad hoc teams for each project or production. Festivals are socially visible because of their status as ‘events’. They are more attractive than year-round music institutions to certain types of people: representatives of politics and the media, sponsors, what used to be called the jet set. Precisely this social visibility can motivate sponsors to commit to a particular festival.

From festspiel to festival: a thumbnail history

The early period: 1900 to 1938

All in all, relatively few festivals were founded in Europe during the first half of the 20th century up to the outbreak of World War II. The earliest were Munich (1901), Strasbourg (1905), Savonlinna in Finland (1912) and the Arena di Verona (1913). But the most important was the Salzburg Festival, created by Max Reinhardt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Richard Strauss in 1920. To the present day it has served as a model for Festspiele in the elevated sense of the term. Remarkably, the foundation of these early festivals was frequently motivated by politics. The Strasbourg Festival, for example, was an obvious declaration of will, on the part of the imperial administration in distant Berlin, to turn the capital of Alsace-Lorraine (German territory since 1871) into a showcase for German culture pointing in the direction of France. The Salzburg Festival was in turn deliberately established, as an act of cultural-political ‘compensation’, to make Austria at least a major pan-European vehicle of culture, a substitute for the disappearance of the Dual Monarchy as a great power after the First World War. In contrast, the Handel Festivals founded in Göttingen (1920) and Halle an der Saale (1922) were designed for the preservation of historical monuments.

After 1933 the political intentions involved in the founding and repurposing of festivals became more obvious. The Heidelberg Castle Festival, which opened with Shakespeare in 1926, was rechristened into a ‘Reichsfestspiele’ in 1934 and subjected to ideological exploitation. The Kassel Music Festival was likewise put to the service of Nazi ideology once its organisers, the Finkenstein Federation (Finkensteiner Bund), had been ‘brought into line’ in 1933 and transformed into the ‘Working Group for Domestic Music Making’ (Arbeitskreis für Hausmusik). Democratic artists were quick to respond: the festivals of Glyndebourne (1934) and Lucerne (1938) were clearly founded in reaction to Hitler’s accession to power in 1933 and the expulsion of Jewish artists following the annexation of Austria in 1938.

Fresh start after 1945

The wounds that World War II had inflicted on the cities of Europe were still unhealed when culture again raised its voice, albeit hesitantly at first. Theatre and opera were mounted in movie houses, concerts were held in churches, and, with a bit of improvisation, the first festivals were again up and running. As early as 12 August 1945 the Salzburg Festival reopened, and on 5 August 1946 the Bregenz Festival launched its first ‘performance on the lake’ on two barges tied to the shore. On 1 May 1946 Hamburg artists performed Chekhov’s Marriage Proposal and Mozart’s Figaro as a gesture of gratitude to the miners of the King Ludwig 4/5 coalpit for delivering coal the previous winter. They thereby gave birth to the Ruhr Festival in Recklinghausen. Finally, on 29 July 1951 the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth was splendidly relaunched as ‘The New Bayreuth’.

People throughout Europe felt a great need for art and culture. New festivals mushroomed out of the ground, beginning with Perugia (Sagra Musicale Umbra) and Cheltenham in 1945, Montreux and the Prague Spring one year later, the Holland Festival, Edinburgh Festival and Ansbach Bach Week in 1947, Aix-en-Provence and Aldeburgh in 1948, and finally, in 1949-50, Dubrovnik, Venice (La Biennale di Venezia) and Berlin. The ‘Chamber Music Performances for the Advancement of Contemporary Music’, founded under the patronage of Prince Max Egon von Fürstenberg in 1921, were revived as the Donaueschingen Festival. Nor was there a short age of new festivals in the years that followed (see Fig. 1). The motivating forces behind the rapid spread of new festivals throughout Europe, notwithstanding their contrasting interests, were primarily humanist in nature. It was not until roughly 1970 that this trend came to a halt.

Stagnation and protest: the 1970s

The next 20 years witnessed conspicuous restraint in the founding of new festivals in what was then West Germany. This was unquestionably a consequence of the student protests of the late 1960s, which irrevocably rocked the foundations of Germany’s perception of culture and its consumption of art. All that deserves mention during this period are the three-day open-air ‘Bardentreffen’ Festival in Nuremberg, founded in 1976 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the death of Hans Sachs, and the ‘Zelt-Musik’ Festival in Freiburg, a saucy crossover mélange that emerged in 1983 from the Classic & Jazz series of the 1970s at Freiburg University.

The festival history in the former state of East Germany took an entirely independent tack. The co-opting of music for political purposes on the one hand, the rise of a less well regulated popular music scene on the other: both are impres sively documented by the festivals founded during these two decades. The Festival of Polit ical Song, one of the largest musical events in East Germany, took place ev ery year in East Berlin from 1970 to 1990. It was offset by the Freiberg Jazz Days, the Dresden International Dixieland Festival, the Leipzig Jazz Days, the Mandaujazz Festival and the Dresden Blues Festival, all founded between 1970 and 1985. The narrow path between political indoctrination and artistic self-assertion was trodden, with greater or lesser success, by two festivals organised by East Germany’s Association of Composers and Musicologists: the Berlin Music Biennale (founded in 1967 and surviving today in the form of MaerzMusik) and the East German Music Days (DDR-Musiktage), held alternately from 1974. One special case was the Dresden Music Festival, founded by decree of East Germany’s Council of Ministers in 1978, which emerged as one of the country’s few platforms for international artists.

In parallel with the insecurity and self-limitations of the classical scene, there arose a new cultural phenomenon, the hippie movement. It developed impressive forums for the presentation of mass culture at Woodstock (1969) and the Burg Herzberg Festival (in existence since 1968). Beneath the enticing slogan ‘out of doors and free of charge’, the years after 1970 witnessed the emergence of a new species of jazz, rock and pop festivals in Germany as a mass phenomenon.

Peaceful revolution and festival boom

The great political upheavals of the early 1990s triggered a new wave of festival foundations, which has since given rise to an international festival landscape of unprecedented density. It all began when the pianist and conductor Justus Frantz founded the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival (SHMF) in 1986. Beneath the banner of ‘classical music in the countryside’, he discovered an untapped market niche, turned churches, manorial homes and barns into concert venues, attracted new audiences to classical music and created a new species of all-embracing, peopleoriented festival organised not around themes but around artists and sponsors. To be sure, he was able to draw on earlier examples, such as the Festival of Flanders (founded in 1957) and Sviatoslav Richter’s legendary festival at La Grange de Meslay. But credit must surely go to Frantz for having combined all these ingredients at just the right time.

Since then the SHMF has itself become a model for new festivals, whether in the former West Germany or, since 1990, in the newly formed states in the eastern part of the country. Examples include the Rheingau Festival, Ludwig Güttler’s successful blend of ‘Sandstone and Music’ and the Festival of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. Especially noteworthy is the explosion of new festivals in the historically and culturally rich states of Saxe-Anhalt, Thuringia and Saxony. These new festivals reveal a tendency to market local stars or regional specialities; they also strive to achieve economic success in the cultural sector by employing the last marketing techniques.

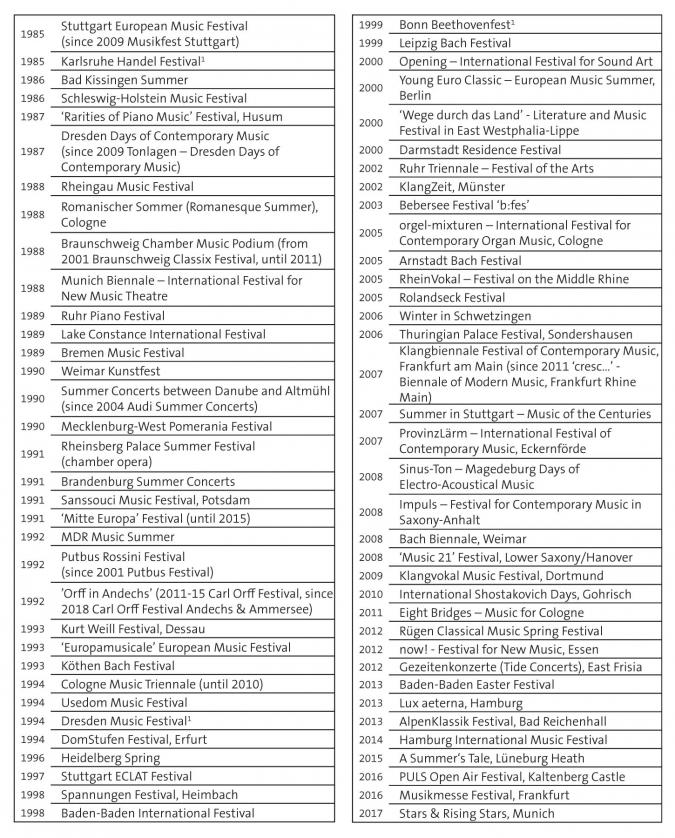

The dramatic increase in new festivals after German reunification (see Fig. 2) is all the more unusual when we consider the dire state of the public coffers and listen to the wide spread laments about the growing unwillingness of sponsors to support culture not to mention the endless debates on orchestral mergers and theatre shutdowns – developments which have continued to the present day. Indeed, one almost wants to speak of ‘festivalitis’. Why, then, do municipalities, companies, private associa tions and die-hard optimists move into the crowded festival market? There can only be one answer: unlike in the post-war years, the reasons have less to do with the will to survive or a realignment on spiritual forces than with hardnosed business interests. Culture, it is said, is a ‘soft’ factor in regional economies, and it produces calculable benefits in so-called indirect profitability (Umwegrentabilität). Both factors have evidently taken hold of the festival idea and turned it into a casebook example of our modern event culture.

Since the start of the new millennium, however, considerable shifts have begun to loom in the festival landscape, at least in the German-speaking countries. Apart from a few large-scale events, mainly in North Rhine-Westphalia (the Ruhr Triennale, the Dortmund Klangvokal Music Festival, the Land.Schaft.Kultur Biennale in East Westphalia-Lippe), it is now mainly short series of events, often founded on private initiatives, that take hold as niche festivals in early or contemporary music.

The fat years come to an end

In recent years the signs again point toward change, and thumbs are directed downward. No fewer than five German music festivals founded in the new century have already folded. The Cologne Music Triennale breathed its last in 2010 after only three festival years, and gave way in 2011 to a new festival, Acht Brücken (Eight Bridges), this time on an annual basis. Yet even this new venture was threatened by cuts in Cologne’s municipal subsidy. Another festival that folded in 2010, owing to low visitor turnout, was the Dortmund Audiodigitale, founded only two years earlier. Similarly, Berlin’s ‘zeitfenster’ Biennale of Early Music shut down in 2014 after 12 years of activity. Even festivals saturated with classical music, such as the Hamburg Ostertöne (first held in 2006) or the AlpenKLASSIK Summer Festival in Bad Reichenhall (founded in 2004), no longer exist, the latter being superseded by a more modest AlpenKlassik Festival Week. The crisis is spreading, not only in Germany. The highly esteemed Salzburg Biennale of Modern Music barely managed to escape financial collapse in 2012; the Tomorrow Festival, held on the grounds of Austria’s Zwentendorf atomic power plant (which never went into operation), had to file for bankruptcy; and the Swiss press reports that the Uncool Festival in Val Poschiavo (founded in 1999), likewise devoted to contemporary music, is at the end of its tether.

Besides the signs of internal erosion that have beset the festival scene in Germany (and not only there), there is no longer any overlooking its fading glamour. For many media, festivals are the same procedure every year. Television companies broadcast at most the opening concerts of the great ‘flagship’ festivals; the nationwide press reports on little more than selected premières; and the interest of crit ics and audiences alike mainly applies to the individual event, not to the cultural phenomenon as a whole.

Particularly worrying is the obvious decline in significance that German festivals have suffered in the international network. The European Festivals Association (EFA), which could look back to a 65-year-history in 2017, lists only Berlin among its 15 founding members, and only five German festivals are found at all among its roughly 100 current members. [5] Europe’s mission to display the wealth and variety of its cultural heritage seems, within the space of a few decades, to have passed from the festival scene to the ‘European Capitals of Culture’, initiated and sponsored by the European Union.

Any turnaround in sight?

How will the festival, as a cultural asset and a business product, fare in the rapidly changing market of leisure activities? The question is harder to answer today than ever before. Positive facts and negative occurrences stand in precarious balance; threatening and startling developments are offset again and again by brave actions with encouraging effects. There has been, for example, an unusually large number of newly-constructed concert halls, lending fresh splendour to musical life not only in large cities (Hamburg, Berlin, Bochum, Dresden) but in the so-called provinces (Erl, 2012; Blaibach, 2014; Künzelsau, 2017). They impart a new quality to Germany’s basic supply of culture. Equally gratifying is the courage of several music enthusiasts to summon new festivals to life, and the risk tolerance of others to give them the necessary jump start. Particularly impressive is the Stars & Rising Stars Festival, launched in Munich on 1 May 2017 with the risky aim of ‘uniting young top-rank artists with stars on stage and many young listeners in the audience’. No less impressive is the name-dropping membership of its board of trustees and steering committee.

Especially astonishing is the number of performing musicians who have emerged as founders and managers of festivals: Rudolf Buchbinder with his Mega-Festival in the Lower Austrian town of Grafenegg; Tabea Zimmermann, who has delighted festival-sated Bonn with a Beethoven Week since 2015; Joshua Rifkin, who has turned one of Bach’s early places of employment, the Thuringian town of Arnstadt, into a festival city; the Fauré Quartet, which covers the Isle of Rügen with a ‘Festival Spring’; and Christoph Poppen, who has even magically transformed an ancient Moorish-Roman fortification in Alentejo, deep in the heart of Portugal, into a festival site. All these musicians stand surely for a new idea of the festival. They bring along their own creativity and musical authority; they deliberately seek niches that bode success outside the mainstream; and they bank on intelligent concepts instead of popular recipes. Is a new optimism called for?

Festivals as enconomic entities

In municipal statutes, the term ‘autonomous economic entity’ (selbstständiger Wirtschaftskörper) stands for the legal capacity under civil law that attaches to a municipality alongside its sovereign rights and obligations. It encompasses the right to acquire, possess and dispose of assets and to operate commercial enterprises. In such cases, a municipality acts like a private company, with the important difference that it is obligated to balance its budget.

Festivals, in addition to their intangible artistic values, cultural significance, tradition and aura, also possess concrete material ‘assets’, whether in the form of venues, ensembles or media exploitation rights. It is therefore incumbent on their directors to display not only artistic authority but business acumen. After all, every artistic decision inevitably has economic consequences, and vice versa.

Art or business?

This question cannot be answered with a simple ‘either-or’, but only with ‘both at once’. Festivals, quite apart from the role they play in local, regional, nationwide or international cultural life with their artistic achievements, are by their very nature business enterprises. Like theatres, concert halls and museums, they are ‘notfor-profit companies’. Unlike businesses in the market econ omy, their economic success is not measured in terms of revenue and profit; the measure of their independent financial power lies entirely in the relation between operating expenses and operating income.

In other words, the acid test of every festival director, year after year, is not the balance sheet but the profit-and-loss calculation. The business operations of festivals, being generally dependent on subsidies, are thus subject not only to commercial pressures but also to monitoring by the public sector. If supported by the private sector, they are also subject to the rules of the market economy, which – as in the case of sponsorships, a well-known instance of one hand washing the other – include the benefits of publicity and the anticipated gain in image. The market may even have repercussions on artistic plans and concepts.

Forms of financing

The ease with which people today speak of ‘cultural sponsorship’ is in fact the result of a development that began some 30 years ago. All German festivals established after the war relied on the support of ambitious municipalities and federal states that could afford a festival as an artistic showcase during the burgeoning ‘economic miracle’. It was not until the mid-1980s that European companies adopted the practice, common in the United States, of sponsoring cultural facilities. Soon they discovered the possibility of using sponsorship, preferably at festivals, not only as a vehicle for self-display but as a means of lowering their taxes. Since then, a mixture of public subsidy and private business commitment has become common practice. The field of cultural management has long employed a special term for this: a ‘mixed economy’.

Armin Klein, in his book Der exzellente Kulturbetrieb, vividly describes the various elements involved in this model of cultural funding. He distinguish es between:

- Public financing

- Self-financing I (revenues)

- New sources of revenue (merchandising and licensing)

- Self-financing II (income from business-related facilities)

- Outside funding I (public)

- Outside funding II (private: sponsorships, foundations, patronage, donations). [6]

Far more so than publicly funded music theatres or orchestras with year-round operations, festivals must ensure diversified funding for their artistic product. Their revenues from ticket sales and ancillary income (advertising, media exploitation, sponsorships, merchandising and licensing) usually far exceed the funds they receive from the public sector (often wrongly called ‘subventions’). Income from business-related facilities (rents, leases) and outside public funding (federal or regional grants, EU allocations) generally plays a minor role. Moreover, most festivals have failed miserably in their attempts to obtain substantial rev enue from merchandising

To simplify, the business activities of festivals can be boiled down to three forms of financing:

- Proceeds from ticket sales and media exploitation

- Funds from the public sector

- Donations from sponsors, patrons, support groups and similar sources.

Festivals financed entirely from public largesse are as rare as those sustained by purely private backing, much less from self-generated income. Examples of the former include the Munich Opera Festival and the Klangvokal Festival, organised by the city of Dortmund. An example of the second type is the Rheingau Music Festival, which is funded almost exclusively by sponsors. In practice, the most common form of financing is a combination of public and private or commercial funding, handled in a great many different ways. The former takes the form of predefined grants or (as with the Salzburg Festival) guaranteed coverage of excess expenditure; the latter comes in the form of sponsorship or, less frequently, donations. A survey of festivals by the Statistical Office of the state of Hessen confirms this: of the common models, the case most frequently encountered was a combination of private and public backing. [7] Festivals are also increasingly choosing the support of foundations, in which case the annual interest earned from the foundation’s capital becomes an additional source of funding.

Quantitative and qualitative economic benefits

The economic effects that greet the eye when we regard a festival as an economic entity fall into two categories: quantitative and qualitative. A 2015 survey entitled Musikwirtschaft in Deutschland (Music business in Germany) attributes ‘annual revenues of at least €5 billion’ [8] to music tourism in Germany, but only €1.2 billion to the consumption of ‘classical music’ (including opera and musical) in 2014, with the trend pointing downward. There was, however, a sharp growth in the proportion of financing from sponsorships, rising from 7.6 to 16.5 per cent in the six years from 2007 to 2013 alone. In the same period, grants from the federal government, states and municipalities sank from 51 to a mere 37 per cent. [9] The conclusion is obvious: where public partners fall short, private backing is needed all the more.

It should at least be mentioned that quantitative economic effects differ, on closer inspection, by the nature of their impact: value creation, income, employment and fiscal. Equally significant, though more difficult to measure, are the qualitative effects, such as improvements in the quality of the location, image enhancement, greater attractiveness for tourists and stronger identification with the town or region involved. These aspects have been amply recognized and verified. The stimulating impact that a festive event can have on a city’s urban life and self-image can be seen in the opening of the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie in 2017, touted as ‘an investment in the future of the city’.

Indirect profitability

Festivals as business operations can be assessed in other ways besides the nature of their economic impact – namely, by the degree to which they influence economic success, including the benefits enjoyed by tourist companies and facilities from the mere existence of festivals. These benefits are known collectively as ‘indirect profitability’. Many studies are in agreement that hotels, restaurants and retail shops have significantly higher revenue and profits thanks to festival visitors.

A survey on this subject, presented by the Bonn Beethovenfest in 2009, [10] comes to the conclusion that the quantifiable direct returns to the city of Bonn, together with their indirect equivalents, add up to more than €2.5 million, and thus doubly repay the city’s subsidy of roughly €1.2 million. The study goes on to claim: ‘Measured against the city’s subsidy, the inflows for the Bonn/Rhine-Sieg re gion increase by a factor of 4.15, i.e. for every euro of the city subsidy, €4.15 flow to companies in the region’. Moreover, the study continues, the festival’s many cooperations with commercial firms and cultural facilities in the Bonn region had ‘valuable networking effects’ that ‘sharpen the profile of Bonn as a focal point of culture and bring about other image effects’. [11]

A study of the economic impact of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, conducted in 2008 to follow up on the above-mentioned study of 1998 (see note 4), arrives at the same conclusion: ‘In 2008 the direct economic effects of the SchleswigHolstein Music Festival amounted to €6.67 million. This excludes indirect effects, in particular the impact on upstream business areas such as restaurants and hotels. Given a subsidy of €1.7 million from the state of Schleswig-Holstein, this means that the SHMF has an economic impact of 3.9 for the state of Schleswig-Holstein. In other words, for every euro of state subsidisation almost four euros return to the Schleswig-Holstein economy’. [12] Much the same was determined in 2018 for the Heidelberg Spring Festival, whose ‘economic impact’ was examined and calculated on the basis of the annual report of 2016 and a visitors’ poll. Here the authors arrive at a profitability factor of 4.05. [13]

Future prospects

Festspiele of the time-honoured sort, and festivals of the new variety, are indispensable for our continuing coexistence. They have always displayed their raison d’être most forcefully in times when culture and humanism were threatened and art was relegated to the sidelines, if not ignored altogether. It was the Festspiele and festivals of France and Germany, Italy and England, that formed the basis for peaceful post-war interaction among the nations. Today it may again be festivals that brighten our endangered existence with at least the semblance of happiness that art can engender. We need Festspiele and festivals more than ever before, and only the petty-minded and ignorant would cast doubt on the necessity of backing them financially.

For this reason, too, cautious optimism is called for. The next decade holds several major anniversaries and festival jubilees in store for us, so that the public sector and private patronage, whether sponsors, foundations or donors, will be unable to avoid generous efforts of financial support. Surely business and tourist interests, the mantra of ‘soft location factors’ and the prospect of indirect profitability will overshadow the artistic impulse and ambitions of the coming welter of events, but in the final analysis they will benefit art and its festive celebration. The first and foremost of these jubilees will be the celebrations of Beethoven’s 250th birthday, proclaimed a ‘national mission’ by Germany’s federal government in its coalition agreement of 2013. In 2020 the city of Bonn will celebrate its most illustrious son in a great many events mounted by the Beethoven House and the Beethovenfest. Moreover, the Beethoven Jubilee Company (Beethoven Jubiläums Gesellschaft), an affiliate of the Beethoven House Foundation, was specially created to plan these celebrations. In addition to its own events, it will coordinate and promote the activities surrounding the jubilee and accompany projects and initiatives from Bonn and the surrounding region with an impressive budget of federal funds.

If Germany will celebrate Beethoven in 2020, Austria will do the same for the Salzburg Festival. Founded 100 years ago in 1920, amidst the misery of the post-war years, it has evolved into a brand that is highly in demand all over the globe. The world of culture rightly looks forward in excitement to its jubilee presentations. Nor will contemporary music receive short shrift: the Donaueschingen Festival, founded in 1921, will celebrate its first centenary. And in 2026 the mother of all music festivals, the Bayreuth Festival, will celebrate the 150th anniversary of its birth. Expecta tions, need it be said, are high.

Footnotes

Harald Kaufmann, ‘Kanon des Festlichen’, Fingerübungen: Musik gesellschaft und Wertungsforschung (Vienna, 1970), p. 107

Wolfgang Ruf, ed., Riemann Musiklexikon, vol. ii (13th edn., Mainz, 2012), pp. 118ff

Harald Hassler, ed., Musik Lexikon, vol. ii, (Stuttgart, 2005), p. 47

Karin Peschel et al., Ökonomische Effekte des Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festivals, Beiträge aus dem Institut für Regionalforschung der Universität Kiel 25 (Kiel, 1998), p. 13.

See https://www.efa-aef.eu/en/members (accessed on 8 June 2018).

Armin Klein, Der exzellente Kulturbetrieb (Wiesbaden, 2008), pp. 207-47.

Hessisches Statistisches Landesamt, ed., Musikfestivals und Musikfestspiele in Deutschland (Wiesbaden, 2016), p. 14

Federal Music Industry Association et al., eds., Musikwirtschaft in Deutschland.: Studie zur volkswirtschaftlichen Bedeutung von Musikunternehmen unter Berücksichtigung aller Teilsektoren und Ausstrahlungseffekte (Berlin, 2015), p. 72.

Information from Dorit Marschall et al., ‘Wirtschaftsfaktor Kultur’, Handelsblatt, Wochenendbeilage (26-28 June 2015).

Lutz Engelsing and Marko Müller, Studie über die wirtschaftlichen Effekte des Beethovenfestes Bonn im Jahr 2009, ed. DHPG (Bonn, [2010]).

Ibid., p. 36.

Stiftung Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival, ed., Das SchleswigHolstein Musik Festival – Zahlen und Fakten zur wirtschaftlichen Bedeutung (Lübeck, 2009), p. 16.

Gesellschaft für Innovative Marktforschung (GIM), Der wirtschaftliche Effekt des Heidelberger Frühlings: Resultate einer Umwegrentabilitätsstudie aus dem Jahr 2016 (Heidelberg, 2018), online at https://www.g-i-m.com/_Resources/Persistent/d2a3ce391d61cdadef9f3070efaa9e76a3c2958a/Umwegrentabilita%CC%88t_HDF_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2018).