For broadcasters, and especially for radio broadcasters, music is a paramount element in their programming. Rightly so, for music is greatly in demand by the population. Of the 16 hours that we spend awake each day, we hear on average more than five hours of music transmitted by the media, most of it via radio and television. [1] In short, broadcast music plays a central role in the daily lives of most Germans. Over the last fifteen years, however, broadcasters have received stiff competition from the musical offerings of the internet. ‘30 million songs. Streaming services such as Spotify or Apple Music offer unlimited access to the songs of humanity. Now anyone can hear anything at any time’, proclaimed Germany’s news magazine Der Spiegel in an article headline in 2016. Eight years later Spotify as well as Amazon has even made it possible to access 100 million songs under the revealing title ‘Amazon Music Unlimited’. At least since the founding of streaming services, including the video portal YouTube, the amount of music accessible online has reached a dimension beyond the scope of descriptive statistics. Moreover, broadcasters themselves are increasingly presenting music online, making it accessible anywhere at any time on many different platforms. As a result, it was sometimes very difficult to separate broadcast offerings in the strict sense from broadcast-like telemedia in the broader sense. However, legislation in the form of the Interstate Media Treaty has clarified this point: ‘Broadcasting’ includes all linear radio and television programmes intended for simultaneous reception and therefore also those that are made available online only for simultaneous reception at a specific time, e.g. via additional live streaming channels. This therefore excludes media libraries or streaming services whose offerings can be accessed at any time and are therefore classified as telemedia. This essay will therefore describe the structure and development of musical content unambiguously assignable to broadcasting and transmitted in the classical sense, whether by analog or digital means.

Legal framework and tasks for broadcasting

The major legal source for broadcasting in Germany is, first and foremost, its Basic Law (Grundgesetz). Alongside freedom of the press, information and opinion, the Basic Law explicitly guarantees freedom of broadcasting as a basic right to which broadcasters, whether public or private, can appeal. The Basic Law assigns culture, and thus broadcasting, to Germany’s federal states (Bundesländer). The states are thus primarily responsible for the legislation, administration and supervision of broadcasting. In consequence, it is statewide broadcasting laws that provide the constitutional framework for the state’s own public broadcasting corporations (Landesrundfunkanstalten). State media legislation does the same for private broadcasters, regulating their authorisation and supervision by the states’ own regulatory authorities. Interstate regulations and laws are set down in so-called ‘state treaties’ (Staatsverträge), which must then be signed by the ministerpresidents of the states concerned and ratified by the states’ parliaments. In 1987, following a series of landmark decisions by the Federal Constitutional Court, the dual broadcasting system was finalised by the federal states in the ‘State Treaty for the Reorganisation of Broadcasting’ (Staatsvertrag zur Neuordnung des Rundfunkwesens). It regulates all the details of Germany’s broadcasting landscape and broadcasting operations, including not only the rules of programming and advertising but especially the division of tasks between public and private broadcasting. It did so as a pan-German state treaty from 1991 on and in the form of the Twenty-two Amended State Broadcasting Treaty until 2020. On 7 November 2020, it was replaced by the Interstate Media Treaty, which, against the backdrop of increasing media convergence, comprehensively regulates not only the tasks of broadcasting but also those of telemedia, including media platforms (e.g. Zattoo, MagentaTV), media intermediaries (e.g. Google) and video sharing services (e.g. YouTube). [2]

Public broadcasters must thus provide basic coverage in terms of a cultural and educational mandate – i.e. wide-ranging, comprehensive and, where possible, balanced offerings in the fields of information, education, culture and entertainment – while paying heed to regional needs. Conversely, to enable them to carry out this mandate with sufficient equipment, organisation and staff, their finances are secured by a compulsory license contribution from every household (Rundfunkbeitrag), known until 2012 as a license fee (Rundfunkgebühr). This gives public broadcasters a guaranteed inventory and developmental potential, ensuring that they can keep pace with and accommodate evolutionary changes in technology, society and culture. To a very limited extent, public broadcasters are also allowed to finance themselves with proceeds from advertising. These proceeds are sometimes viewed with suspicion, especially by private broadcaster associations, given that income from license contributions amounts to more than €8 billion annually, with ARD receiving approximately €6 billion, the ZDF €2 billion and Deutschlandradio €250 million. It seems legitimate, however, to view advertising information as part of a comprehensive information coverage involving products, services, and sometimes political parties in run-ups to elections.

Private broadcasters need only fulfil a so-called basic standard (Grundstandard), i.e. their programming does not follow a cultural and educational mandate and need not satisfy criteria of diversity and balance. Nonetheless, they must adhere to certain rules, e.g. regarding child protection, personality rights and other constitutional principles, including the inviolability of the dignity of the individual.

This is ensured through monitoring by external commissions or by the state media agencies (which are likewise financed via license contributions) so as to offset their power to influence opinion. Public broadcasting is organised along democratic lines through broadcasting commissions (Rundfunkräte) with representatives from relevant areas of society, including musical life. This involves the state music councils in particular, but also composer organisations (with the Bavarian Broadcasting Corporation) or the State Academy of Cultural Education (Saarland Broadcasting Corporation). Public broadcasting is thus subject to social control. Private broadcasters, in contrast, are chiefly sustained by specific business, media or political groups as shareholders. Since they are wholly financed through advertising proceeds, their entire programme can be geared to the market, to viewer and listener ratings and lucrative target groups. Germany’s private television broadcasters receive some €4 billion annually through advertising, with private radio broadcasters receiving roughly half a billion. Nevertheless, despite their market orientation and lack of an educational mandate, private broadcasters are likewise enjoined by the State Treaty to contribute to Germany’s cultural diversity in their programmes. This can and ought to be a key criterion in the granting of licenses by the state media agencies.

Organisational structure and channels

Public and private broadcasters alike offer a wide range of channels, various degrees of which are taken up by music. In addition to the music sections described below, both public and private stations broadcast programmes that talk about and provide information on music in various forms. This ranges from interviews with musicians to reports on concerts and themed music history programmes.

Public broadcasting

Germany’s nine state-run public broadcasters – WDR (North Rhine-Westphalia), BR (Bavaria), hr (Hesse), SR (Saarland), radiobremen and the multi-state broadcasters NDR (Northern Germany), MDR (Central Germany), SWR (South-western Germany) and rbb (Berlin-Brandenburg) – operate altogether seven regional television channels known as Germany’s Third Television Channels. As the Association of Public Broadcasting Corporations in the Federal Republic of Germany (ARD) they jointly present the nationwide television channel known as ‘Das Erste’ (The First) as well as the digital educational and cultural channel ARD alpha. The ARD is also responsible for the children’s channel KiKA (‘Kinderkanal’, in cooperation with ZDF), the tri-national cultural channel 3sat (in cooperation with ZDF, the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation and the Swiss TV broadcaster SRG SSR) and the Franco-German cultural channel ARTE (with ZDF and France Télévisions). The Second German Television Channel (ZDF) also operates the digital channels ZDFinfo and ZDFneo. The channel ZDFkultur, specialising in music, cinema and the performing arts, had a strong inclination toward nostalgia, airing reruns of such popular music shows as ‘Melodies for Millions’, ‘Musik liegt in der Luft’ (Music Is in the Air), ‘Show Palast’ and ‘ZDF Hit Parade’. It was discontinued in 2016.

Depending on the size and the cultural heterogeneity of its transmission area, each state broadcaster also offers from four to eight analog radio stations with contrasting contents and listener segments, thereby helping to fulfil its programming mandate as a whole. All these can also be received digitally nationwide via DAB and live stream on web radio. Except in the case of hr, rbb and SWR, each state broadcaster also has up to four additional radio stations which, owing to VHF spectrum scarcity, can be received only digitally via DAB in their home transmission area. All in all, state broadcasters offer 69 radio channels, of which 14 can only be received digitally. Although ZDF does not have radio stations of its own, it joins forces with ARD to carry the public radio broadcaster Deutschlandradio with its three nationwide stations Deutschlandfunk, Deutschlandfunk Kultur and the digital pop channel for young adults, Deutschlandfunk Nova. Deutsche Welle (DW), a public broadcaster under federal law subject to regulatory oversight by the federal government, represents Germany’s international broadcaster, with a large emphasis on information and a small amount of music. The increasing trimedial orientation of broadcasters, which takes into account that different media channels for programme content - radio, television and online - are increasingly converging, does not stop at the music departments of these broadcasters, even if large parts of the music-related programme still have to follow media-specific production logics.

In keeping with their cultural and educational mandate, almost all the state-run broadcasters maintain their own music ensembles. This amounts to more than 20 ensembles, including high-quality symphony orchestras, big bands, radio and chamber choruses and one children’s chorus (MDR). According to a report from the former parliamentary enquète commission on culture, Germany’s state-run broadcasters thus represent the largest producer of music in the world. By commissioning new works, often from young and little-known composers, and by performing, recording and broadcasting more than 1,000 concerts annually (including many world premières) [3] in every region of Germany, they play a crucial role in the diversity and evolution of the international contemporary music scene. They function as initiators and sponsors of concert series (e.g. BR’s musica viva) and as organisers and facilitators of music competitions (such as the ARD International Music Competition in Munich) [4] , music festivals (Donaueschingen, Witten Days of New Chamber Music) and school initiatives (the ARD’s music outreach project in conjunction with the German Music Council) [5] , and are constantly involved in the cultural policy of federal and state governments in their capacity as major promoters of culture.

Private broadcasting

As regards television, private broadcasting in Germany is dominated by two companies: ProSiebenSat.1 Media SE and the RTL Group SA. The latter is 76.28 per cent owned by Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA, one of the 20 largest media concerns in the world. Based in Munich, ProSiebenSat.1 Media SE owns the nationwide television broadcasters Sat.1, ProSieben, kabel eins and sixx as well as several smaller broadcasters. The Cologne-based RTL Group SA holds 100-per cent ownership of RTL and the news broadcaster n-tv and part ownership of RTL II, Super RTL and VOX. Of niche broadcasters, special mention should be made of Deluxe Music, MTV and VIVA (until 2018), which specialise entirely in music. However, for years the number of broadcasters has undergone a steep decline. One main reason is doubtless that the broadcasters, owing to their small transmission area, usually have negative profits. In other words, many programmes cannot be sufficiently capitalised on the local market, and cultural programmes in particular are usually cost-intensive.

Especially worthy of mention are Schlagerparadies (Hit Tune Paradise) and Klassik Radio, whose programme offerings can be inferred from their very names. Both operate on the nationwide level as digital broadcasters but sometimes make use of local VHF backup frequencies.

‘Music has been a major, if not the major, component of radio programmes in Germany since the very inception of broadcasting.’

Music in radio programmes

Music has been a major, if not the major, component of radio programmes in Germany since the very inception of broadcasting. The first music broadcast on radio, a classical concert from Vox House in Berlin, was transmitted on 29 October 1923, thereby establishing so-called ‘entertainment radio’ (Unterhaltungsrundfunk), which was celebrated with radio programmes and exhibitions to mark its centenary. In early years the broadcasters had music performed by their own ensembles, usually live. This practice was retained, and in the decades that followed the broadcasters’ own symphony orchestras could brook comparison with the best ensembles in the world and hire conductors of comparable stature. However, the advantages of broadcasts from gramophone recordings quickly took hold (see ‘Professional Orchestras’). Along with the emergence of rock and pop in the 1960s, the post-war baby boom ensured a high demand from young listeners for such broadcasters as Radio Luxembourg. Consequently, with a substantial time lag, Germany in the 1970s likewise saw the emergence of such youth-oriented and pop-heavy stations as SWF 3. The so-called ‘service waves’ (Servicewellen) of the 1970s offered an uninterrupted programme with a clearly defined spectrum generally oriented on mainstream music. The spoken parts were broadcast at fixed times every hour and were never more than three minutes long, giving listeners a simple and reliable programme structure.

From the mid-1980s three types of programming dominated Germany’s radio landscape:

- Information, news and talk programmes

- Full-service programmes, e.g. ‘middle of the road’ (MOR)

- Music-based programme types which, compared to the other two, revealed the greatest variety and differentiation.

Three aspects were taken into account when conceiving music programmes:

- the style or genre of the music

- the target group, usually in the form of age groups, but occasionally divided by income, education and cultural background

- the style of moderation, form of presentation and sometimes the overall impression of the sound.

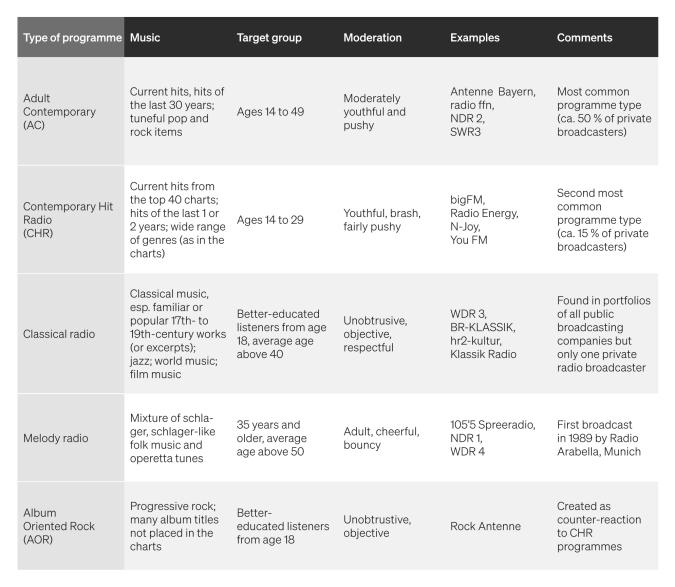

The most important types of music-based programmes in Germany’s radio landscape are discussed below, in each case, where possible, with examples from private and public broadcasters (see Fig. 1).

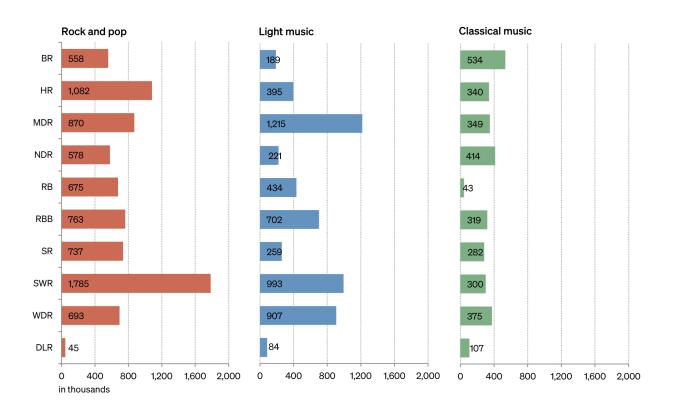

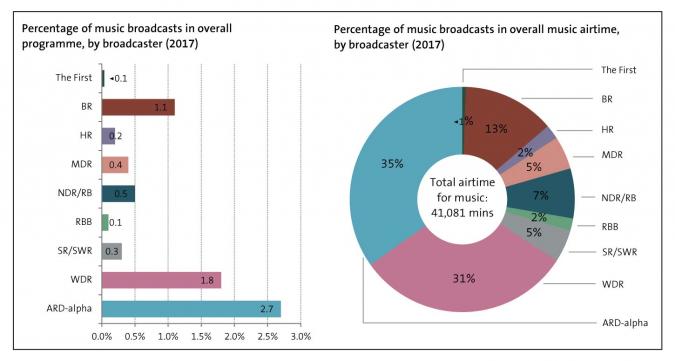

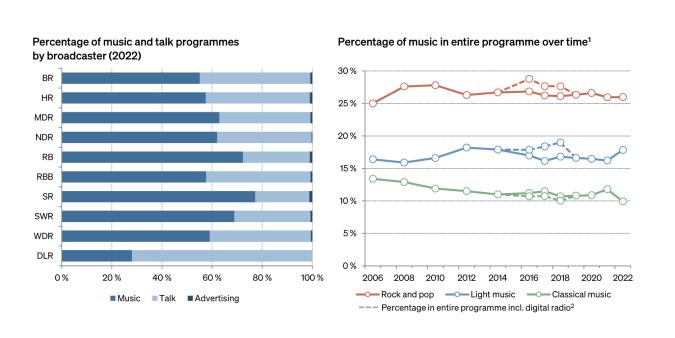

The amount of music in music programmes is on average roughly 70 per cent, although the exact proportion of music and the share of individual music genres in the overall programme is difficult to determine because the boundary between programmes with and without music is becoming increasingly blurred and different broadcasters set their own standards and criteria for the classification of programme categories and music genres. [6] The percentage is higher on average for private broadcasters than for public broadcasters, mainly because the state-run public broadcasters, in addition to AC, CHR and ‘Melodieradio’ channels, also have more heavily informative cultural programmes and, especially, exclusive information and news channels in their portfolios. As a result, the public broadcasters have an average of 63 per cent music over all their channels (or 28 per cent in the case of Deutschlandradio, with its news ‘flagship’ Deutschlandfunk). Unchanged for years, 26 per cent of the overall programme falls on pop and rock music, 17.8 per cent on so-called Unterhaltungsmusik (‘light music’, i.e. hit tunes, pop standards, operetta melodies and folk music) – with an upward trend – and a fifth on classical music – with a downward trend (see Fig. 2). Analyses by the German Broadcasting Archive for the years 2016 to 2018 (since 2019, the German Broadcasting Archive has no longer been entrusted with this task; statistics for digital channels have no longer been published since then) clearly reveal that many stations massively increase (in some cases almost double) their daily output of pop and rock music through their digital channels. This is slightly different in the case of light music, which some stations do not broadcast at all on digital channels. In contrast, light music dominates such broadcasters as BR, which has shifted large parts of its light music to the digital area to channels such as BR Heimat (folk music) and BR Schlager (hit tunes and standards). Classical music does not figure at all in the digital channels of most state-run broadcasters, except in the case of MDR, with its digital channel MDR Klassik. [7]

In the wake of the debates on cultural and musical diversity in radio programmes, and given that many European countries have quotas for home-grown music, Germany too has, over the years, constantly faced the question of how much German-language music (or at least music created by German composers and lyricists) should be aired in radio programmes, and what effects this might have. [8] There is no overlooking, or overhearing, that German-language music currently bulks large on the charts and programmes of the broadcasters with the largest transmission areas.

Music market research from radio broadcasters

Unlike public radio broadcasters, private radio broadcasters rely completely on income from advertising. The higher the ratings and the larger the transmission range of their programmes, the greater the proceeds to be earned. It thus comes as no surprise that most private radio broadcasters bank on an AC programme and play current hits as well as super-hits from the last 30 years – a mixture most to the liking of the relevant target group, listeners from 14 to 49 years old. However, as a 14-year-old will generally not have the same taste as a 49-year-old, it is no easy matter to develop music programmes viewed positively and used regularly by a maximum number of listeners. Nonetheless, attempts have been made to do just this on the basis of music market research, which determines what music is accepted by which listeners (for this reason it is also called ‘acceptance research’). Along with the expertise of radio producers, these research findings are the most important factor in deciding what pieces will be broadcast, i.e. which will enter the so-called ‘playlist’. [9] The playlist includes all the pieces a broadcaster wishes to integrate in its programme, regardless of whether they are aired frequently (several times a day) or rarely (two or three times a year). It represents the musical repertoire of a given radio station. In the case of AC broadcasters, a playlist rarely has more than 1,000 titles, more likely between 200 and 500. There is a trend toward ever-smaller playlists, especially among CHR broadcasters, which often take the ‘top 40’ idea quite literally.

Two test procedures are especially common in music market research. The first, callouts, is used by most radio broadcasters and forms the central criterion for planning their music programmes. Every week, or at least every two weeks, some 50 hooks (striking excerpts from a piece that last roughly eight to 12 seconds and presumably have the highest recognition value) are rated by up to 200 randomly selected people from the target group. Each title is evaluated by these people according to several criteria, usually familiarity (‘Have you heard this piece before?’), pleasure (‘Do you like this piece?’) and saturation (‘Would you like to hear this piece more often on your favourite radio programme?’). Callouts are used in particular to test pieces which are played very frequently on radio and thus have a high rotation level and are more likely to reach saturation. In this way, when certain parameters are met, pieces can be included in or excluded from the programme in a timely manner.

In contrast, auditorium tests are more complex and costly, and are therefore financed by radio broadcasters only once or twice a year. A group of up to 500 people of the target group is invited to a hotel, cinema or auditorium. There they are played several hundred (or sometimes as many as 1,000) hooks and asked to evaluate them using the three above-mentioned criteria. Auditorium tests are suitable for testing large sections of a playlist, i.e. including those pieces not found in the highest rotation level.

The test results are transferred to target group-specific ratings or socio-demographic subdivisions. From there it is easy to infer which pieces are liked more, or liked less, by which listeners. The degree to which the findings enter programming policy varies from one broadcaster to the next. Programme-makers at culture channels generally do not use market research at all. They rely primarily on the expertise and experience of their music editors. In addition to this type of market research, both private and public broadcasters are increasingly using data from online market research and from data collected via their own online feedback channels or their own websites for their AC and CHR programmes with large transmission areas. Whereas until a few years ago, market research data across all stations were more important than the assessment of the music editors for creating music content, this has reversed in recent years: the music editors are now clearly in the lead because the private stations in particular are giving the music editors a stronger position compared to previous years. However, there may also be financial reasons for this, as market research is a crucial cost factor that needs to be reduced or at least scrutinised in the face of decreasing advertising revenue due to the stations' dwindling reach. [10]

Music offerings on web radio

Since the mid-1990s a great many music radio broadcasters and channels have been added to the internet. The internet has obvious advantages as a medium for radio: it offers unlimited space and does not need to struggle with spectrum scarcity. An internet radio broadcaster does not require a large investment or a license, so that programme makers face very low hurdles for entering the market. Moreover, given the low costs, only low revenues are necessary in order to remain profitable. In this light, the providers do not need large transmission areas and can aim at very small target groups with niche and special-interest portfolios.

In Germany, the first broadcasters to go online with their terrestrial radio programmes were Deutsche Welle in 1994 and, one year later, B5 aktuell, the information broadcaster of Bavarian Radio. DSL and flat-rate tariffs have favoured the growth of internet radio in Germany, as their high transmission rates have now led to a sound quality almost equivalent to CD standard, thereby even surpassing the qual ity of terrestrial broadcasters. Smartphones, laptops and radios with internet capability have made mobile reception possible anywhere at any time.

The following types of content have taken hold, whereby only the first can be categorised as broadcasting:

- Live stream, where the programme is broadcast in a particular time slot and all listeners hear the same thing at a given time;

- On-demand streaming, where a programme can be accessed individually at any time via streaming and not all listeners hear the same thing at a given time;

- Podcasting, where programmes are downloaded via a web feed in the form of audio files and stored on the end device (e.g. a smartphone, iPod or laptop).

‘Pure’ internet radios (online-only web radios) can be distinguished from those whose programme can also be heard one-to-one terrestrially via VHF or DAB (simul cast web radios). Aggregators, such as liveradio.de, bundle and structure this large range of internet radios, but do not provide programmes of their own. Music portals work in much the same way, but are usually more heterogeneous, bundling not only internet radios but all manner of music portfolios. Especially worthy of mention are streaming services such as Apple Music or Spotify, which additionally offer music programmes assembled and supervised by their own producers. The online-only web radios are increasingly fed in the form of user-generated radio streams. Here individual users can offer their personally selected music programmes for downloading by other listeners and build up a veritable fan base. As a result, the offers are sometimes very specialised. Music niches and the smallest target groups can be addressed. Radio listeners can hear specific music programmes independently of temporal and spatial constraints, and thus anywhere at any time, tailored to suit their personal needs.

Music on television

Ever since Germany’s public television was founded in the 1950s, music broadcasts have been a permanent part of the programme inventory. Cult broadcasts such as ‘Beat Club’ (1965-72), ‘Disco’ (1971-82) and ‘ZDF Hit Parade’ (1969-2000) remain unforgotten. This same applies to ‘Formel Eins’ (Formula one, 1983-90), which already presented music video clips four years before the launch of MTV Europe (1987) and ten years before VIVA started in Germany (1993). Equally unforgotten, for many Germans, are the great Saturday evening shows such as ‘Anneliese Rothenberger gibt sich die Ehre’ (Anneliese Rothenberger has the honour, 1971-81), ‘Ein Kessel Buntes’ (Potpourri, 1972-92), ‘Musik ist Trumpf’ (Music is trumps, 1975-81), ‘Musikantenstadl’ (Minstrel barn, 1983-2015), ‘ARD Wunschkonzert’ (ARD special request show, 1984-98) and ‘Melodien für Millionen’ (Melodies for millions, 1985-2007). Judging from viewer ratings and follow-up responses, the transmission of the ‘Eurovision Song Contest’ or the ‘Helene Fischer Show’ on Christmas Day numbers among the television highlights of many Germans every year. Folk music festivals, held several times each year, and weekly casting shows such as ‘The Voice of Germany’ and ‘Deutschland sucht den Superstar’ (Germany’s Got Talent) also continue to enjoy a loyal audience of millions. [11]

A glance at television offerings which place their main focus on music, and can unquestionably be categorised as music broadcasts, reveals the following types of programmes:

- Concert broadcasts (e.g. operas, festivals, Live Aid)

- Music shows, special request concerts (e.g. ‘Musikantenstadl’)

- Hit parades, chart shows (e.g. ‘ZDF Hit Parade’, ‘The Ultimate Chart Show’), Nostalgia shows (e.g. ‘The 70s/80s/90s Show’)

- Music films (e.g. Comedian Harmonists)

- Music quizzes (e.g. ‘Erkennen Sie die Melodie’ [Name That Tune])

- Music competitions (e.g. ‘Eurovision Song Contest’)

- Music casting shows (e.g. ‘The Voice of Germany’).

There are also many programmes in which music, though prominently showcased and present during large parts of the broadcast, is not the main focus of the show, which is therefore usually classified under ‘entertainment’ rather than ‘music’ in broadcast statistics. This is true, for example, of dance competitions (‘Let’s Dance’, ‘Got to Dance’) and other shows and entertainment broadcasts. Definitely excluded from the ‘music’ category in the statistics are films, series, game shows, quiz shows, documentaries and advertising spots, even though music functions in the background during large parts of the broadcast and formatively influences the way the programme is shaped and experienced, thereby contributing to the daily consumption of music. Today 90 per cent of all advertising spots alone make use of music. [12]

In short, the importance of music in broadcasting is greatly underestimated in standard broadcast statistics, where in the case of most public broadcasters it makes up less than 1 per cent of broadcast time. The WDR is already the leader here with a share of 1.4 per cent. This share of music in WDR's programme alone accounts for more than a third of the total music output of all public broadcasters of just over 28,000 minutes per year, which corresponds to only 0.6 percent of total broadcasting time.

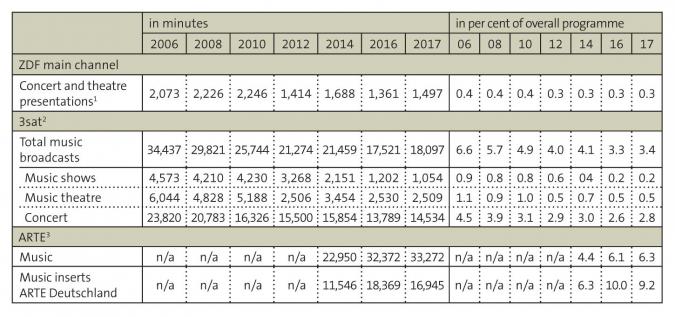

Germany’s Second Television Channel (ZDF) makes no distinction between concerts, music theatre, spoken theatre, cabaret and variety shows in its category ‘Concert and Stage Offerings’ and subsumes many music broadcasts under the heading of ‘entertainment’. As a result, music broadcasts allegedly make up only 0.3 per cent of its programme offerings. The cultural channel 3sat at least distinguishes between music theatre, music shows and concerts, thereby arriving at a broadcast proportion of 3.3 per cent over all three categories, though the figure has tended to decline in recent years. In the case of ARTE, music at least reaches a level of 4.6 per cent, as we know from a special study of its programme categories Opera, Classical Concerts, Pop Concerts, Maestro, Musica and Performing Arts (concerts, shows, circus and ballet), carried out for the German Music Information Centre (see Fig. 4), which corresponds to just under 24,000 broadcast minutes, around half of which was contributed by ARTE Deutschland. Yet here, too, the importance of music is underestimated, for some music broadcasts are included under the heading of ‘Documentaries’ or ‘Culture’. Likewise missing in the statistics is the online music programme ARTE Concert (concert.arte.tv), which presents more than 900 performances and concerts every year, half of them in live-stream broadcasts.

Pure music broadcasters such as MTV or Deluxe Music continue to occupy a special position. Their programmes consist for the most part of music video clips, and thus unquestionably of music broadcasts, and thus make up a sizable proportion of the overall music offerings on television. However, they have lost in popularity. In the 1990s MTV and VIVA still formed the everyday ‘visual radio’ for many young people, and even had an impressive 2.2 to 2.3 per cent market share among 14- to 29-year-olds in 2006 (shortly before the advent of the smartphone era). MTV Germany discontinued standard operations in 2011, after which it could only be received on pay TV until the end of 2017. Since then, the programme has again become accessible on free TV and live stream via its home page and the MTV Play App. [13] VIVA, although constantly available on free TV in the 2010s, had to share its broadcast time on the assigned channels again and again with alternating broadcasters such as Nickelodeon and Comedy Central. As a result, it ran only 12 hours per day and ceased operations entirely at the end of 2018 after 25 years of broadcasting.

Prospects for the future

Although broadcasting services have decreased in importance among teenagers and young adults over the last ten years, 64 per cent of all Germans continue to use television and 68 per cent radio on an average day, and thus inevitably hear broadcast music. [14] These figures derive particularly from the older half of the population, which grew up with analog media in the 1950 to 1980s and has largely retained its media habits. On the other hand, the music offerings on radio and television have proliferated over the last ten years, thanks to digital channels and platforms, and adapted to accommodate increasingly specialised target groups and needs. Broadcasters are now making most of their diverse services available for reception via media libraries, regardless of time, and are thus becoming telemedia providers that compete with international streaming platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, Spotify or YouTube for the favour of media users. Thus music has, in principle, a worldwide marketplace on which users of smartphones and streaming services can hear exactly what they want anywhere at any particular moment. At present, greater flexibility and individuality is barely conceivable. Nor is it conceivable that people of the future will be content with less.

This development is linked to questions about the future of broadcasting: private broadcasters are gradually losing the traditional advertising income for their broadcasting services, as fewer and fewer people are using the current or linear live television and radio programmes. They must therefore generate alternative sources of revenue from their telemedia services or market both types of offerings together. Public broadcasting does not have a financing problem due to the licence fee, but it does have an acceptance problem. If more and more people are no longer using public broadcasting at all, according to the argument often put forward by critics of the broadcasting licence fee in its current form and amount, then there should also be a discussion about a potential reduction in the breadth and depth of services and a greater division of tasks between public broadcasters. It is to be feared that various cultural sectors, and thus also music in its various forms, will give way at the expense of broad and mainstream-oriented cultural reporting, that the costs for cultural programmes in general and for the broadcasters' ensembles in particular will be reduced or that entire broadcasters could possibly be dissolved or merged with other broadcasters. Public broadcasting has been involved in precisely this discussion for years - with politicians, with society and with itself. The outcome is uncertain, but what is certain is that the diversity of the broadcasting landscape will be accompanied by the diversity of music in this country. Preserving and safeguarding this diversity has been one of the most important tasks of public broadcasting.

Footnotes

See also Holger Schramm et al., Medien und Musik (Wiesbaden, 2017), esp. pp. 2-5.

For an account of the current state broadcasting treaties, including the Interstate Media Treaty, ARD Staatsvertrag, ZDF Staatsvertrag, Deutschlandradio Staatsvertrag, Rundfunkfinanzierungsstaatsvertrag, Rundfunkbeitragsstaatsvertrag and Jugendmedienschutz Staatsvertrag, see Media Perspektiven 1 (2024), online at https://www.ard-media.de/fileadmin/user_upload/media-perspektiven/Dokumentation/4._MAEStV_MP_Dok_2024_I.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2024).

See Bericht über die wirtschaftliche und finanzielle Lage der Landesrundfunkanstalten (April 2004), p. 45, online at https://www.landtag-bw.de/files/live/sites/LTBW/files/dokumente/WP13/Drucksachen/3000/13_3141_D.pdf .

The ARD International Music Competition in Munich, held since 1952 and now organised by the Bavarian Broadcasting Corporation, is one of the largest and most prestigious classical music competitions in the world. It has launched the careers of many artists who are world-famous today. Every year, around 200 musicians from around 35 to 40 countries and five continents compete in four annually changing categories.

At two-year intervals schoolchildren from all over the country, beginning with the fifth grade, are invited to compose pieces of their own in music classes, each year inspired by the music of a different composer (Dvořák in 2014, Vivaldi in 2016, Handel in 2018, Beethoven in 2020). The state-run broadcasting corporations support the project by supplying free teaching materials, video tutorials and a special composing software package. The best works are performed in a final concert broadcast on all the cultural channels of Germany’s state-run broadcasters, the Third Television Channels and on live stream video in the Web.

See Wolfgang Gushurst, Popmusik im Radio: Musik-Programmgestaltung und Analysen des Tagesprogramms der deutschen Servicewellen 1975–1995 (Baden-Baden, 2000), p. 231.

Since 2017 MDR has bundled its classical activities in the brand MDR Klassik with subcategories radio, online and social media. The brand also includes the ensembles MDR Symphony Orchestra, MDR Leipzig Radio Choir and MDR Leipzig Radio Children’s Choir, as well as the MDR Summer Festival and the label MDR Klassik.

Already surveyed by Klaus Goldhammer et al., Musikquoten im europäischen Radiomarkt: Quotenregelungen und ihre kommerziellen Effekte (Munich, 2005).

See Holger Schramm et al., ‘Wie kommt die Musik ins Radio? Stand und Stellenwert der Musikforschung bei deutschen Radiosendern’, Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft (2002), pp. 227-246.

See Holger Schramm and Fabian Mayer, ‘Wandel der Musikprogrammierung im Radio? Stand und Stellenwert der Musikforschung bei deutschen Radiosendern 2021’, Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft (2023), pp. 112-129.

The history of music broadcasts on television is discussed in Irving Benoît Wolther: ‘Musikformate im Fernsehen’, in Holger Schramm, ed., Handbuch Musik und Medien: Interdisziplinärer Überblick über die Mediengeschichte der Musik (2nd edn., Wiesbaden, 2018).

For an historical overview of music in advertising see Benedikt Spangardt et al., ‘Musik in der Werbung’, in Schramm, Handbuch (see note 11).

On music TV broadcasters see Daniel Klug and Axel Schmidt, ‘Musikfernsehsender’, in Schramm, Handbuch (see note 11).

See Thomas Kupferschmitt and Thorsten Müller, ‘ARD/ZDF-Massenkommunikation Trends 2023: Mediennutzung im Intermediavergleich’, in Media Perspektiven, 21/2023, pp 1-20.