Just as music can assume many different forms, the professions directly or indirectly associated with it are equally wide-ranging and varied. Ever since the days of Ancient Greece, theoretical or scholarly studies of music have complemented practical music-making and become a key element of European musical culture. In a larger context, this also involved all those who created the prerequisites for these various professions and activities, whether in a physical sense (e.g. instrument makers) or by research and teaching, including the passing on of performance tech niques. At first these complex activities were normally carried out by a single person (e.g. a composer-organiser-performer), but over the years music profes sions have become increasingly varied, differentiated and specialised. This has giv en rise to interactions, dependencies and changing relations between music and those who deal with it professionally, all of which unfold within music history and social history alike. [1]

Roughly since the mid-1990s there has been a noticeable increase in the thought given to the future viability of education in many music professions. The reasons lie in the profound changes that music has undergone as a result of economic and social globalisation. Particularly relevant are demographic and sociological developments and the transformations they entail, not only in the social practice of music, but in its reception and consumption. No less relevant is the massive impact of digi tisation and new media on the communication of music, affecting every area of its production and distribution. Equally influential are global changes and their associated economic processes.

In this light, music professions are dependent on five factors: social evolution, technological advances, artistic innovations, economic conditions and the appreciation accorded to music by society. Conversely, it is safe to assume that the effectiveness of many music professions will in turn impact the evolution of musical culture. Music professions thus will only have a future if music education is consistently provided by qualified teachers, especially among children and adoles cents. Thus, the music teaching professions both inside and outside the state education system are increasingly important, as the German Music Council already pointed out in its two ‘Rheinsberg Declarations on the Future of Music Profes sions’ in 2007 and 2009.

‘Diversity in education, language and communication skills, flexibility and a willingness to achieve will prove more decisive than ever before in determining the professional opportunities’

Overview

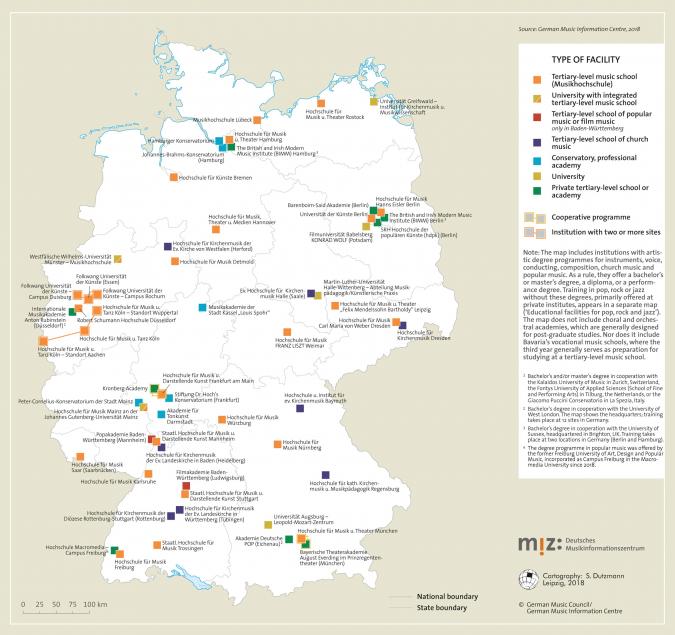

In Germany, training for music professions is sustained by a wide range of specialised institutions: tertiary-level schools of music (Musikhochschulen), teacher training colleges, universities, polytechnics, church music schools, conservatories, music academies, vocational training colleges (only in Bavaria), special public or private institutes (e.g. for popular music or theatrical professions) and specialised training centres for instrument building.

The highly specialised nature of educational programmes for music professions contrasts with the overlapping and duplicated course offerings among the various types of tertiary-level institutions concerned. The differences among these institutions are the result of their divergent historical, regional or conceptual traditions and implicitly touch on aspects of prestige, significance and quality. Thus, music teachers for the state school system receive their training at Musikhochschulen or universities, or, at a regional level, at teacher training colleges; church musicians can choose courses at Musikhochschulen or special tertiary-level schools of church music; and degrees for instrument or voice teachers are offered not only by Musikhochschulen but by music academies, conservatories and even several universities. One special instance is Bavaria’s vocational training colleges (Berufsfachschulen), which function as the first stage in professional education. The training lasts two years and ends with state certification in ensemble or choral conducting or a comparable degree in popular music.

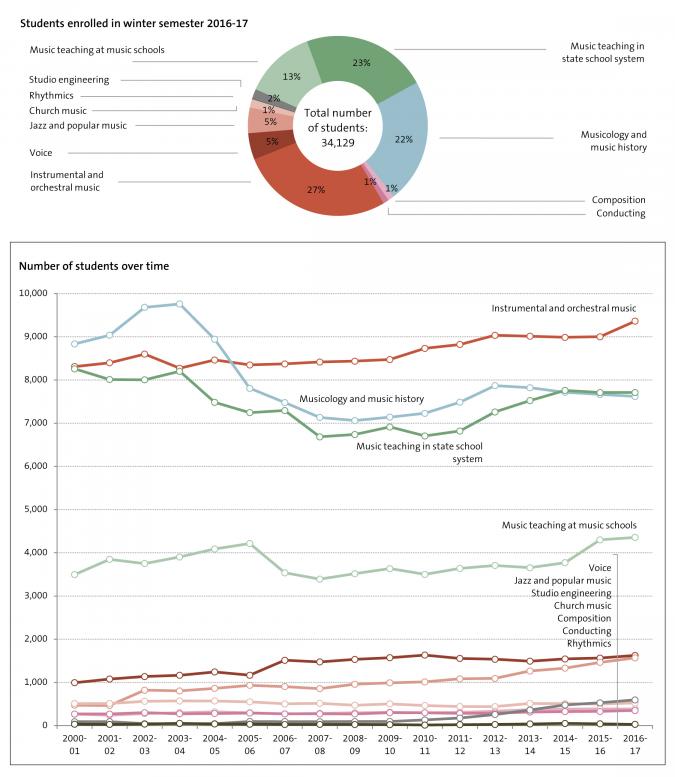

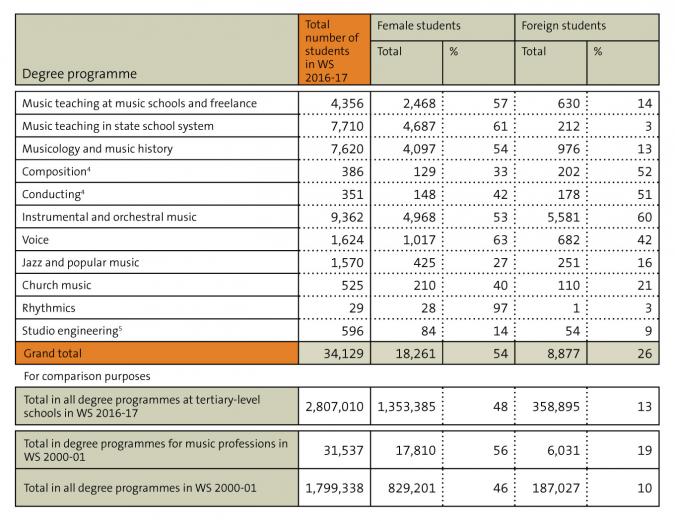

In the winter semester of 2016-17 roughly 34,000 students were enrolled in degree programmes for music professions at a university level (excluding conservatories and music academies), with more than 55 per cent attending Musikhochschulen. Roughly 40 per cent of the students were trained as practicing musicians; nearly a third sought teaching certificates; and 22 per cent pursued degrees in musicology (see Fig. 1).

The growing demand for international compatibility of degrees, called for since 1999 by the so-called ‘Bologna Process’, and the resultant introduction of bachelor’s and master’s programmes have led to fundamental structural reforms in the tertiary-level study of music. The duration of degree programmes has also become more differentiated: for performance and composition, the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany (KMK) has prescribed four years for a bachelor’s degree (BA) and an additional two years, if desired, for a master’s (MA). Apart from that, at least three years are envisaged for a bachelor’s degree at university level, and an other one or two for a master’s. [2] The Bologna Process has led many tertiary-level institutions to set new emphases and to introduce new courses of study, thereby creating many possibilities for individual profiling among the students and new options for interdisciplinary coursework.

Training for performers and composers

Musical training in the narrow sense relates first and foremost to the practical activities of musicians as instrumentalists, singers, orchestra conductors, choral and ensemble directors, or musical authors (composers, arrangers or similar professions). Accordingly, these forms of education have traditionally stressed ‘major subjects’ or ‘main instruments’ such as piano, cello, horn, choral conducting or composition. The subcategories in this field focus mainly on the repertoire to be studied and relate to potential areas of professional activity and/or generic specialisation, e.g. solo artist, orchestral musician, lied, opera or oratorio singer, big band, instrumental ensemble, chamber music, early music, contemporary music, jazz, popular music, film soundtracks or electronic music.

The principal centres for obtaining professional training in performance, composition and conducting in Germany are its Musikhochschulen, some of which date far back in history, having been founded as conservatories in the mid-19th century. They are organised either as self-sufficient entities or as part of a larger institu tion covering several art forms. Two of them, the Folkwang University in Essen and the University of the Arts in Berlin (UDK), have even achieved university status. Often they combine their course offerings with training in theatre or dance, as in Hamburg, Rostock, Cologne, Munich, Leipzig, Frankfurt and Stuttgart. Conversely, they can offer non-artistic degree programmes, such as media management or media and music (at Hanover Hochschule for Music, Drama and Media) or cultur al and media management (at Hamburg Hochschule for Music and Theatre). The Musikhochschulen are spread among Germany’s federal states in varying levels of concentration: there are five in Baden-Württemberg, [3] four each in North Rhine-Westphalia and Bavaria, two each in Berlin and Saxony, and one in most other states.

In terms of legal status, the 24 Musikhochschulen are grouped together in the Conference of Rectors of German Conservatories (RKM). Being state-run institutes of higher learning in the arts, they have the following goals and missions:

- to impart artistic and educational knowledge and skills,

- to develop and communicate knowledge in musicology and music theory

- to conduct research initiatives in scholarly disciplines and artistic development projects, and

- to guide students in mastering their craft.

One way that the RKM pursues these goals is through three competitions devoted either to artistic practice (Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Competition, in cooperation with the RKM since 1963), to music education and communication (Music Education Competition, since 1952) or to innovative concert formats (‘D-bü’ Competition, initiated in 2017).

Besides the option of studying at independent Musikhochschulen, music degrees can also be obtained in Mainz (where the Musikhochschule is part of Mainz University), Münster (where it is part of Münster University) and at various conservatories or music academies (generally in conjunction with a Musikhochschule). A few private educational establishments also offer courses of study in special fields such as singing or popular music. One example is the Popakademie Baden-Württemberg, a facility operated by the state of Baden-Württemberg in cooperation with the city of Mannheim and partners in the media, making it a Hochschule and skills centre for the music business and the music scene rolled into one.

The prerequisite for starting a course of study in music is proof of special musical and artistic aptitude, which is determined in a lengthy process tailored to the degree programme concerned. The very large number of contestants for places of study at Germany’s learning institutes in the arts is international in scope, and the question is often asked whether the number of foreign students should be restricted. In winter semester 2016-17, for example, 60 per cent of students enrolled in instrumental and orchestral music were from foreign countries, along with 52 per cent in composition and 51 per cent in conducting (see Fig. 3). The selection process is based on many different factors, of which the most important is the severe demands the students will later face in a profession aligned on artistic excellence. Even so, it is uncertain whether, or to what extent, these students will have opportunities to work in the profession they have chosen to study.

Another discrepancy between course of study and professional outlook, at least in some disciplines, results from the percentages of female students. For example, 42 per cent of students enrolled in conducting programmes in the winter semester 2016-17 were women, even though female conductors continue to be woefully underrepresented, especially in orchestras (see also Gerald Mertens’s essay ‘Orchestras, Radio Ensembles and Opera Choruses’).

Although the course offerings centre on the practice of music (e.g. an instrument, voice, composition or conducting), they are also combined with secondary fields of study such as music theory or musicology. Now that degree programmes in the arts have been converted to the BA/MA system, the previous advanced or special ist degrees have been mainly subsumed in master’s programmes. Increasing importance has recently been attached to specialisms in concert education, music appreciation or music management.

A special combination of music and applied science is offered by the studio engineering programmes at Berlin and Detmold as well as the audio-visual engineering programme held jointly by the polytechnic and Musikhochschule in Düsseldorf. Interested students can also take a degree in music design at the Musikhochschule in Trossingen. Other public and private facilities likewise offer training and advanced studies in this field. Degree programmes in church music are similarly noted for combining artistic subjects with other disciplines, particular theology and, increas ingly, education (see Meinrad Walter’s essay ‘Music in Church’). Another educational task is assumed by the opera studios attached to various opera hous es, which seek a more practical orientation. Nine opera houses have entered cooperations with Musikhochschulen, in which case the course units are shared with the Hochschulen; otherwise they are held entirely in the opera house. Although such co-operations are generally welcomed, the co-ordination of these two quite different institutions can create problems, not least because educational facilities place different expectations and standards on their students than opera houses do on their ensemble members. [4]

Finally, music therapy is currently offered at six of Germany’s higher education institutes, generally as a master’s programme. The aim is to achieve broad musical, therapeutic and scholarly expertise capable of functioning in several professional areas, such as working with disabled, elderly or traumatised people.

All these institutions are under great obligation to provide optimum preparation for students’ future careers, which are generally very difficult in the arts. This obligation is best described in terms of practical training related to the needs at hand, and thus as a balanced and personalised combination of excellence, selforganisation, self-motivation and individual initiative. Given this situation, the early promotion of musical talent has gained in importance at Germany’s Musikhochschulen, especially over the last decade. Many tertiary-level institutes have set up programmes specifically for the promotion of gifted children. This reflects the special nature of artistic development, which necessitates long, intensive and high-quality study prior to the onset of professional training (sometimes even at the pre-school level), especially in such instrumental subjects as violin, cello and piano.

Training for music teachers

Educational activities in the state school system

The training and professional profile of music teachers for Germany’s state school system are rooted in the early history of its church and municipal school traditions and the voice lessons offered there for various functional purposes. Building on the reforms initiated by Leo Kestenberg in the 1920s, [5] music was introduced in the state schools as a field of instruction. To the present day prospective music teachers are trained on the basis of a three-tier model that integrates artistic, scholarly and educational components. A second phase consists of an internship (Referendariat) in which a solid theoretical training is related to practical tasks specific to the teaching profession.

In the first tier, teacher training differs fundamentally depending on the form of school at which the student seeks to teach. Training for Germany’s grammar schools (Gymnasien) and for many schools of secondary level I (which bear different labels depending on the state involved but generally cover grades five to nine or ten) calls for two major subjects, such as music and mathematics, plus additional coursework in education, often augmented by units in psychology. In response to the challenges posed by the growing number of languages at Ger many’s schools, a mandatory or ‘obligatory elective’ subject in German as a second language (‘Deutsch als Zweitsprache’, DaZ) is sometimes added as well. The degree programmes also include lengthy periods or even full semesters of practical application in order to gain a clearer view of the profession and to align studies with the demands of day-to-day school operations. The resultant links lead to meaningful cooperations between tertiary-level institutes, teacher training colleges and state schools.

The Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) has ratified requirements for subject areas and methodology in teacher training pro grammes. [6] Though intended to regulate this field and to create nation wide compatibility, they have been implemented in quite varying ways by institutions in the various states. For primary schools, which generally cover grades one to four (but also grades five and six in some states), and for special schools, [7] the coursework largely relates to mandatory subjects or majors (usually German and math ematics), optional electives or combinations of subjects (including music) and courses in education, augmented as applicable (see above). The number of course credits devoted to electives differs markedly from state to state, and in the case of music it sometimes lies beneath a meaningful level for qualified teaching at primary schools.

Music teachers at Germany’s grammar schools (sometimes combined with teaching positions at comprehensive schools, or Gesamtschulen) receive their training primarily at Musikhochschulen. [8] Several universities also offer a course of study in this field. Training for music teachers at other types of school is largely the responsibility of universities and teacher training colleges (see Fig. 4), though in some states this field is also offered by Musikhochschulen.

All educational institutions require prospective music teachers to pass an aptitude test before being admitted to a degree programme. In recent years this test has been considerably improved and expanded in its quality. Rather than functioning as a sort of subjective measuring stick for artistic potential, it has become a sophisticated prognostic tool for determining a student’s aptitude for the teaching profession, by including such criteria as communication skills and basic abilities in ensemble direction and music-making in schools.

In recent decades the contents and methodology of teacher training courses in music have changed markedly in the face of professional reality. Among the changes are the inclusion of relevant subjects (e.g. popular music, digital media, ethnomusicology and the handling of equipment) and the communication of a broad range of activities in music instruction (e.g. co-operative learning methods, classroom management or project work). There have also been shifts in the acquisition of musical skills that lend greater weight e.g. to classroom piano and instrument performance, improvisation, ensemble work, and choral and vocal training for children

In sum, it has become essential for students to receive an opportunity to work out personalised pathways in their studies. This also applies to advanced scholarly work in music education and musicology (doctoral degrees and inaugural dissertations).

Thanks to the conversion to bachelor’s and master’s degrees, many educational institutions have been able to reassess their teacher certification programmes and to interact more closely with other courses of study in the interest of achieving ‘polyvalence’. We hope to see solid investigations of these new structures in the near future, enabling them to be corrected and improved.

The second phase of teacher training, preparatory service, usually lasts 18 months. Legally independent, it serves to expand the practical skills that students acquire for the teaching profession during their studies. Usually it comes to an end with a state examination. [9] The training sought for teacher certification takes place at university departments or schools of education as well as at state schools. It is provided by trainers with special scholarly and practical expertise, supported by suitable teachers in the state schools. During this preparatory service, the training combines theoretical instruction, sample lessons and theory-guided reflections related to music instruction. Besides events at training colleges, special importance is accorded to job shadowing and classroom teaching, whether supervised or independent. Although the under lying KMK paper explicitly warns against it, the amount of independent instruction is quite large in many states, some times already beginning at the start of the training period. The suspicion there fore arises that the training character of preparatory service is being summarily dismantled in an effort to offset the current shortage of teachers

One special form of training for music teachers is the so-called ‘dual subject teacher’, i.e. a teacher with ‘music as an extended subject of instruction’, which is offered in several states for grammarschool teachers. [10] This allows prospective teachers to acquire a specific musical profile that enables them to set points of emphasis both in classroom instruction and in the life of their school (e.g. classroom music-making and choral, band or orchestral work). On the other hand, owing to the absence of a second (or even third) subject of instruction, it is often more difficult for school authorities or headmasters to employ such teachers flexibly in their day-to-day school operations.

At present it is not possible to meet the need for qualified music teachers in all forms of public schools, nor is this likely to be the case in the future, given the changes in society, the aging of music teachers and the growing number of pupils. The shortage of trained music teachers, espe cially in primary schools, is part of a larger problem, namely, the shortage of teachers altogether. The employment of later entrants and career changers, though promoted by regional ministries of education, will not solve the under lying problems; rather, it will lead ineluctably to a creeping de-professionalisa tion of the music teachers’ calling (see Ortwin Nimczik’s essay ‘Music in Germany’s State Education System’). From this vantage point, job prospects for fully qualified music teachers in the general education system can be called quite promising.

Teaching instruments and voice outside the school system

The training of instrument and voice teachers for use outside Germany’s general education system, especially at public and private music schools or in a selfemployed capacity (sometimes in co-operations), takes place at Musikhochschulen, music academies, conservatories and in some cases at universities. [11] Here, too, before embarking on this course of study the student must pass an aptitude test. Besides theory and ear training, these tests have largely been content with examining the students’ musical competence through an audition in their chosen field. With regard to the combination of core subjects, these institutions barely differ in their course requirements: a main instrument or voice, a second instrument, theory, ear training and musicology are generally compulsory, as are courses related to the teaching profession (instrument or voice education, methodology, music psychology, vocational issues and internships with test teaching sessions or the like).

The breadth of subject matter called for in public music schools by the school curricula and the ‘Music Education Plan for the Elementary and Primary Level’ [12] is reflected in the training given to instrument and voice teachers. Besides a mastery of their voice or instrument, teachers are expected to have acquired educational, scholarly and methodological abilities and skills during their studies. As late as the 1970s training was based around individual lessons. But the traditional image of the instrument or voice teacher has substantially expanded with changes in the day-to-day reality of teaching, the inclusion of elementary music and lifelong learning in public music schools, and the co-operative supervision of wind, string and choral classes in the general education system.

Thus, the teaching qualifications acquired today relate to the training of amateurs of every age and every level of proficiency. They include preschool lessons as well as training for a professional career and cover every recognised form of instrumental and vocal instruction, from individual lessons to the teaching of large groups. Instructors now have to pass on additional skills, e.g. in improvisation, elementary ear training, organology, dance, physical movement, stage acting and the basic treatment of the human voice. Moreover, greater expertise in musicology, music education and psychology is crucial, particularly in view of the altered nature of the profession. Scholarly work in instrumental and vocal instruction has been singled out for expansion at various learning institutions, paving the way for scholarly certification (doctoral degrees).

Not least, the political initiatives that have gained increasing social significance under the names of ‘JeKi’ (short for ‘Jedem Kind ein Instrument’, or ‘An Instrument for Every Child’), ‘JeKits’ (‘Jedem Kind Instrumente, Tanzen, Singen’, or ‘Instruments, Dancing and Singing for Every Child’) or ‘JEKISS’ (‘Jedem Kind seine Stimme’, or ‘Every Child Has Their Own Voice’) will succeed only if instrument and voice teachers command additional expertise in broad-based music education. The same applies to co-operative wind, string and choral classes, which now exist in every type of school in every federal state. They are generally taught jointly by state school music teachers and instrument or voice teachers. Both courses of study have given rise to new educational tasks resulting from the large number of instruments, the divergent levels of motivation and the structure of small and large groups. These tasks can only be efficiently carried out, on the basis of the modular BA/MA system, if new forms of teaching the curricula are incorporated on a trial basis in the early conceptual stage of educational and interdisciplinary events.

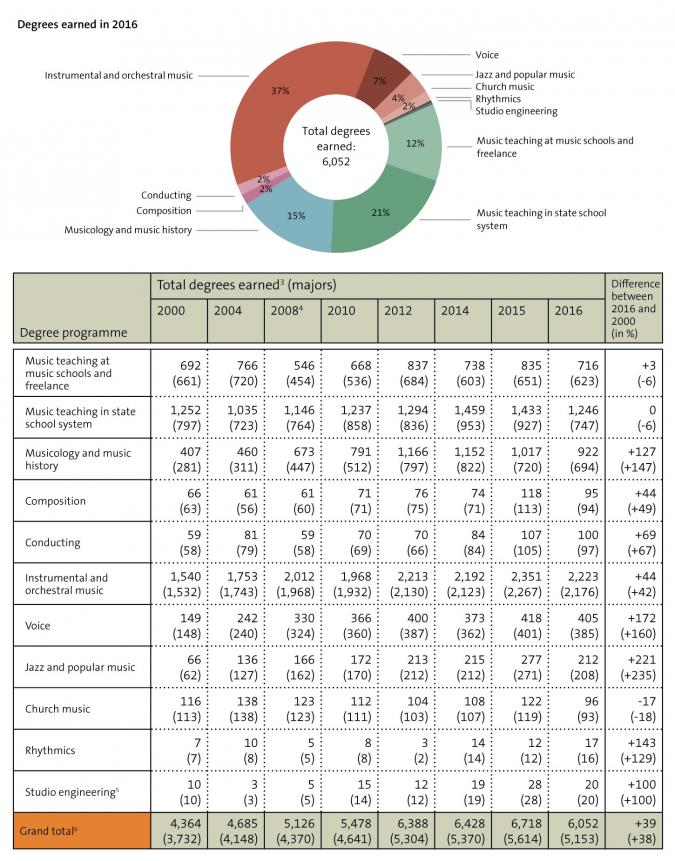

Every year over the last six years some 600 students successfully completed degrees majoring in instrument or vocal teaching at Germany’s institutes of higher learning (see Fig. 5). The relatively large number of degrees in this area partly results from the fact that many students (e.g. orchestra majors) use the degree to expand their career prospects, thereby avoiding the generally tight job market for artistic professions in favour of neighbouring fields of activity or augmenting their original chosen profession.

Another course of study for activities outside the state school system is elementary music education, or EMP (Elementare Musikpädagogik), which has a special task in connection with public music schools, day care centres, primary schools, retirement homes and church congregations. EMP initiates and promotes ‘learning music with all the senses’, e.g. through singing, physical movement, listening to music, improvising and playacting, regardless of the age or proficiency of the learn ers. [13] In view of the ongoing changes in society and culture, EMP teachers are facing new areas of work that require preparation at tertiary level: cultural dialogue in teaching children from migrant families, overlapping areas of instruction for primary and special schools, and educational advancement and special training in music for educators, primary school teachers and special education teach ers. In all these areas there still exist training deficits because, alongside the musical and technical demands, additional educational requirements have arisen that have bare ly been addressed to date.

Besides the new points of emphasis within current educational structures, the past years have also witnessed the introduction of many course offerings, frequently as master’s degree programmes, with emphases of their own, e.g. on music appreciation/concert education, music therapy or training for special age groups (conducting children’s and youth choirs). This is an added benefit of the BA/MA system: it opens up opportunities to strike a balance between artistic and educational perspectives and to work more deeply and purposefully toward professional qualifications that go far beyond the traditional picture of an instrument or voice teacher. Still, to complete a degree is not tantamount to entering the workforce as an instrument or voice teacher. Moreover, the working conditions and payment of casually employed instrument and voice teachers (e.g. owing to temporary contracts and varying numbers of lessons) are constantly subject to debate. Professional associations and unions are currently working to change this situation. Viewed in this light, the straightforward image of an instrument or voice teacher is destined to become obsolete. Instead, we will face a new type of teacher working in different fields with various employers. Yet precisely the patchwork nature of these music-educational activities can make them attractive.

Taking together all these aspects of the expanding professional image, the need for broadly trained instrument and voice teachers will grow in the near future. Public or private music schools will still form the hub of professional activities in all their variety. Thus, from the standpoint of the Association of German Music Schools (Verband deutscher Musikschulen, or VdM), the core responsibility of traditional instrument and voice instruction will remain intact. The students’ career prospects will depend directly on the breadth of courses offered at their particular Musikhochschule, university or conservatory, and on the open-mindedness of the students themselves.

Prospects for the future

Despite the long, intensive and high-level training necessary in the arts, professional prospects after graduation are generally hard to predict. In particular the German job market for orchestral musicians has changed significantly over the last 20 years, especially given the roughly 20 per cent decline in permanent jobs owing to the disbandment or merging of orchestras since 1992 (see also Gerald Mertens’s essay ‘Orchestras, Radio Ensembles and Opera Choruses’). Similar trends can be noted in music theatres and professional choruses. To be sure, the so-called ‘free music market’ grants opportunities to play in or establish ensembles on a freelance basis, often with groups specialising in early or contemporary music. How ever, this frequently leads to the vagaries of self-employment and to patchwork careers that rarely manage to cover basic living expenses. [14]

In the teaching professions, it is already becoming clear that the need for cooperative ventures in music education inside and outside the school system will grow at most Musikhochschulen and universities. This extends from co-operations between EMP and music-related primary schools to modules involving wind, string and choral classes. Besides these co-operative modules, there will be more and more points of emphasis in elective areas, which will give rise to additional degrees. In conjunction with this, new fields have already emerged, e.g. with senior citizens and other social strata.

At present the Federation of German Associations for Music Education is working on an overall plan, called ‘Musical Education 2030’, that will point out networking possibilities among different providers of music education in a new concept. In particular it will illustrate the deficits at day care centres and primary schools as well as afternoon instruction at all-day schools. Compounding the difficulties is the striking shortage of teachers, particularly music teachers, which dramatically prevents music instruction from being provided continuously and progressively in the general education system. Germany’s teacher training programmes will have to respond to this. Another source of extraordinary difficulty is that there are, at present, practically no satisfactory teaching concepts for the inclusion of the disabled, which has now been introduced nationwide. Here the educational know-how is simply missing, and must first be developed and implemented in training programmes.

For musicologists, too, traditional job areas are likely to be increasingly augmented by adult education and cultural programmes for senior citizens. Now that musicology programmes have clearly responded to recent changes in society and the job market, it is also safe to assume that the differentiation and expansion of course offerings will help to open up new fields in music management, music documentation and the new media (see Dörte Schmidt’s essay ‘Musicology’). Still, diversity in education, language and communication skills, flexibility and a will ingness to achieve will prove more decisive than ever before in determining the professional opportunities for musicologists.

Footnotes

See e.g. Walter Salmen, Beruf: Musiker: Verachtet – vergöttert – vermarktet: eine Sozialgeschichte in Bildern (Kassel, 1997).

The possibility of a four-year bachelor’s programme in music education has also been discussed, but it still awaits consistent nationwide application.

In 2014 Baden-Württemberg, in a conference on the future of tertiary music education (‘Zukunftskonferenz Musikhochschulen’), defined special points of emphasis for its five institutions with the goal of assigning particular focuses to each Musikhochschule. See also https://mwk.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/hochschulen-studium/hochschullandschaft/hochschularten/kunst-und-musikhochschulen/zukunftskonferenz-musikhochschulen (accessed on 19 October 2018).

Constanze Wimmer and Domen Fajfar, Opernstudios im deutschsprachigen Raum: Eine Bestandsaufnahme, ed. Körber Foundation (Hamburg, 2017), (accessed on 19 October 2018).

Leo Kestenberg (1882-1962) was music advisor to the Prussian Ministry of Science, Art and Popular Education from 1920 to 1930. He introduced a comprehensive reform of music education sustained by the notion of long-term music instruction from kindergarten to university incorporating the conservation of folk music and all the professional institutions of musical life.

Ländergemeinsame inhaltliche Anforderungen für die Fachwissenschaften und Fachdidaktiken in der Lehrerbildung, KMK Resolution of 16 October 2008, version of 16 May 2019, online at https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2008/2008_10_16-Fachprofile-Lehrerbildung.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2019).

Special schools give individual support to children and adolescents who are limited in their development and learning potential, e.g. owing to physical disabilities. At present the status of special schools varies widely owing to the different speeds and concentra tion at which ‘inclusive conceptions’ have been implemented from one state to the next

The only tertiary-level music schools in Germany that do not offer training for music teachers in the state school system are the Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin, the Robert Schumann Hochschule in Düsseldorf and the Hochschule für Musik in Nuremberg.

Those aspects affecting all the federal states are outlined in the KMK paper Ländergemeinsame Anforderungen für die Ausgestaltung des Vorbereitungsdienstes und die abschließende Staatsprüfung, KMK Resolution of 6 December 2012, online at https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2012/2012_12_06-Vorbereitungsdienst.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2018).

This training option is offered in Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia, Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein, Thuringia and to a certain extent in Baden-Württemberg. Rather than studying a second subject, the trainees expand the subject of music to an appropriate degree.

See the map ‘Music Education and Music Therapy Outside the School System’ in the German Music Information Centre’s Musikatlas.

Lehrpläne des VdM (Kassel, 1990- ) and Bildungsplan Musik für die Elementarstufe/Grundstufe, ed. Verband deutscher Musikschulen (Bonn, 2010).

The Bildungsplan Musik (see note 12) presents a highly accurate picture of what is absolutely necessary in elementary education, including such key components as the integration of disabled people and children with migrant backgrounds.

See Orchestermusiker/in der Zukunft: Studie Sommer/Herbst 2014, ed. Junge Deutsche Philharmonie (Frankfurt am Main, 2015) (accessed on 19 November 2018).