IAMIC, the International Association of Music Information Centres, is an international network of currently 33 members who document and promote the music of their country or region. The range of activities of each of the members varies, according to the context in which they operate, however as with many international networks, the similarities of purpose and intent far outweigh any differences.

Music is a complex artform, across genres and styles, modes of presentation and delivery and consumption, purpose or intent, connecting with various audiences. It is also a language that expresses culture and identity – across a spectrum from artmaking to commerce; either specific to community, or to place, or to mass popular appeal.

When anyone attempts to navigate across the landscape that is music, or to explore the music culture of a particular place – its infrastructure and developments, its composers and artists etc – they need to find a reliable reference source. It is this that forms the core of what a music information centre (MIC) does.

A short history of IAMIC

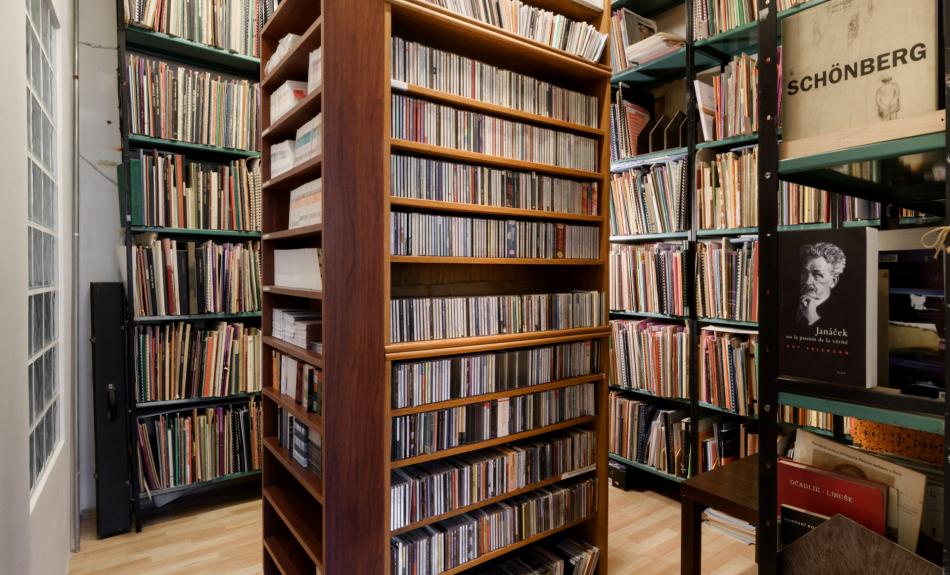

While there are a variety of business models and content approaches that MICs operate under in their local context, the origins of the network go back to music libraries. MICs such as New Music USA (formerly the American Music Centre) was established in 1939, maintaining a library collection of works by American composers, both scores and recordings.

Others came later (e.g. Gaudeamus Foundation in 1947; Canadian Music Centre in 1959 etc), and in 1960, there was the first informal meeting of a group of Music Information Centres at the IAML Conference (International Association of Music Libraries) in The Netherlands. This came out of two previous meetings in 1958 and 1960, convened by André Jurres from the Donemus Foundation in Amsterdam, under the auspices of the International Music Council, held in Amsterdam, and bringing together ten to twelve organisations that were involved in the promotion of contemporary (art) music.

By 1962 this group of organisations had become a formal constituent branch of IAML, and continued to meet at IAML conferences, sharing their experiences and knowledge. In 1986, growing activity and membership of this group led to the setting up of IAMIC, with the intention of functioning independently under its own by-laws and Board. With the (then) emphasis of some countries’ MICs being the promotion and marketing of contemporary art music, its range of tasks became broader, and was no longer limited to the documentation activities (librarianship) of the community that IAML represented.

The emergence of a network

After much discussion over a number of years, the IAMIC by-laws were formally adopted in 1991 by some 40 member MICs, and this ended the direct affiliation with IAML.

By this time the activities of some MICs had become more diverse, with many involved with publishing (of scores, recordings, texts etc), artist development and promotional projects, and even music presentation through performances and festivals.

During the 1990s the membership of IAMIC gradually expanded. By the end of the century there were some 47 members, with newer members (for example from Austria, Germany, Iceland, Bulgaria, Georgia, New Zealand), all bringing with them new perspectives and new expertise. And new organisations continued to emerge, in response to geopolitical, technological, and socio-cultural evolution; or in response to outreach by IAMIC in attempting to be more global, and less Euro-centric in its spread – a challenging task in a volatile marketplace, where creative expression and culture sometimes struggle against ebbs and flows.

MICs online

The emergence of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s revolutionised the business of information management and dissemination, and further shifted thinking from a domestic marketplace to a more global perspective. While many MICs were early in providing online catalogues (one of the first was Australia, in 1993), by the middle of the decade several MICs made moves to begin the task of digitising their collections – the Canadians and British were amongst the earliest to begin this process, and others soon followed. Discussions in IAMIC during the late 1990s increasingly focussed on how the network might best exploit the possibilities of online dissemination of, and create more visibility for, music content.

A joint project around this time between eight European members was initiated by the (then) MICA – Music Centre Austria – exploring how cataloguing data from each participating member might be accessible through a single online interface drawing on multiple databases. The outcomes from this initiative were mixed, but many valuable lessons were learnt, and shared amongst IAMIC members, informing their future collaboration. The shift from a contentcataloguing focus to a broader business focus of modern information – and content – management had begun.

Alongside this, some MICs expanded their focus beyond contemporary art music, embracing other music genres, though others were already operating in this space (Austria, Germany, Flanders, and the Nordic MICs). An inevitable result of this expansion, which increased over the past two decades, was a shift from the purely documentation activities that many MICs undertook to a more strategic emphasis on music as a transactable and exportable commodity. This addressed not only the cultural imperatives that drove the activities of MICs, but also the sustainability imperatives that faced MICs and the music landscape that each represented. The emergence of the music export office model (initially established in Sweden, based on thenevolving models from Australia amongst others), began a trend that we have seen spread in recent years, with some of these music export infrastructures replacing the role of the MIC, and others working alongside the MIC.

Into the future

While a shift away from documentation activities might be lamented by some, it points to broader imperatives of music infrastructures (and funders – often collecting societies or government agencies) in addressing the questions of sustainability, and even survival, in addition to the kind of cultural documentation and promotion that characterised the early years of IAMIC. As previously mentioned, each geographic context is different, so the model of what a MIC can be, and the activities it might undertake, still varies greatly.

But the common threads that bind this IAMIC community continue to be relevant and valid, and this is reflected in the current IAMIC purpose of increasing international co-operation, increasing the mobility of artists and the circulation of works, and increasing the international visibility and dissemination of music of all genres. And IAMIC members involved in music promotion, development, documentation, export, information and content management, research and the support of creation and production, provide a strong basis for the network to continue to thrive into the future.