Musicology takes music as its object of study, and thereby makes it an integral part of the current scholarly landscape. At the same time it provides a foundation and supplies personnel for many tasks in musical culture and education that are not strictly artistic in nature. It is currently found, in a wide range of methodologies, at most German universities, all tertiary-level schools of music and many research facilities outside the university system, from the Musical Acoustics Research Group at the Fraunhofer Institute of Building Physics in Stuttgart (IBP) to the Beethoven Archive in Bonn. Moreover, given the very wide range of interests it covers, music often becomes an object of study in related disciplines. Musicological topics and methods are also brought to public attention by museums, libraries and archives, whether public or private, and by varied activities in theatres, orchestras, broadcasters and publishers, not to mention the seminal importance of music education at state schools. Musicological expertise affects scholarly and cultural administration, professional associations, cultural policy and the creative economy in many ways. We take this so much for granted that the fact that musicology provides or influences the qualifications of people working in these wide-ranging fields is frequently overlooked – yet another consequence of music’s firm foothold in academia.

Musicology, in its various branches, allows our society to reflect, with all the methods at its disposal, what it regards as music and what place and functions it assigns to it. Reflections of this sort go hand in hand with an historical awareness of the origins and mutability of music itself and the ways that we can learn from it. That a community should devote attention to the subject in this way at all – i.e. that it should establish an academic discipline devoted to reflecting on music and situating it in the system of scientific knowledge – tells us something about the value of music in our culture. It is indicative of the constitutive importance and epistemological function that we attach to music in all its many manifestations, even beyond its direct sensual and aesthetic perception. The notion that the methodological approaches to music thrive on the scientific possibilities that are available to us for understanding the world, and which help to define what we are able to view and understand as music at all, has continued to apply to the discipline to the present day. The institutional landscape in which musicology in Germany is embedded – a landscape largely based on public funding – secures a vision of culture in which cultural and artistic practice and aesthetic perception are elevated to objects of reflection and sources of knowledge. The constitutional lawyer Dieter Grimm sees this as the bedrock for society’s ideational reproduction: ‘In this light, culture would embrace everything related to the interpretation of the world, the imparting of meaning, and the establishment, transmission and critique of values as well as their symbolic expression, not excluding so-called counter- and subcultures’. [1] In this view of culture, the many manifestations of music form part of a sphere of social negotiation in which a democratic community obtains a clearer picture of its societal and cultural underpinnings.

A democratic state is fundamentally dependent on such a sphere of negotiation, for unlike an autocratic state it cannot simply proclaim or promulgate its legitimacy by fiat but must establish it through culture. This is precisely what is negotiated in art, humanities, sciences, education and culture, which for this very reason must be free. They must be autonomous but not self-sufficient, i.e. not independent of the state but rooted in its very foundations. In consequence, the significance of culture, and particularly of music, in our constitution does not reside in its having a particular form, that is, one reducible to stereotyped features of a state or nation. Rather, it resides in assigning a central place in this sphere of negotiation to the encounter with and investigation of music. The state represents and secures this central place by anchoring both music and musicology in public institutions of higher learning (state schools and universities). Combining this assurance with the demand for autonomy also fashions prerequisites for change and evolution while opening up possibilities for reflection into the future.

The international scope and crosslinking of musicology as a discipline may be taken as a sign of the widespread dissemination of just such beliefs. In this way musicology participates in the protection, transmission and promotion of that musical diversity which the UNESCO Convention of 2005 declared to be an essential component of cultural diversity. Musicology shares the motivation stated in the Convention’s preamble – namely, ‘that cultural diversity forms a common heritage of humanity and should be cherished and preserved for the benefit of all’ – as well as its central goals, particularly to ‘raise awareness of [cultural diversity’s] value at the local, national and international levels‘. [2]

That music and its principles have become an object of scholarly investigation at the university level has much to do with the public self-perception of its significance for the cultural fabric of society. It arose from the educational emancipation of the middle classes: beginning in the mid-19th century the practical training of musicians became an academic pursuit leading to the foundation of conservatories and institutes of tertiary-level education. Many of these institutes, being at the level of ‘higher learning’ in the educational hierarchy, offered women in particular an opportunity to obtain degrees comparable to the German Abitur (school leaving certificate) even before they were allowed to attend grammar schools or universities. In parallel with practical training, musicology, in its initial phase, was placed methodologically in the old philosophical faculty, which initially made no distinction between social sciences, natural sciences and the humanities, and thus included not only language and literature, history, art history and so forth but also mathematics and physics. Precisely these institutional interactions made and continue to make musicology a lively and protean discipline, despite its focus on problems of source criticism and art history.

The efforts of the Prussian cultural politician Leo Kestenberg and his comradesin-arms from the 1920s to include music in the grammar-school curriculum on a par with humanities and sciences can be seen as a consequence of the mutual relations between the practice, study and teaching of art. These efforts, the effects of which can still be felt today, were aligned not only on the practice of music but also on thinking about music. In this way Kestenberg laid the cornerstone for the dual artistic and scholarly qualification of music teachers at the university level, a qualification still customary today. Since then musicology, too, has had a place of central importance in the training of teachers. [3]

The fact that Germany’s Basic Law (Grundgesetz) includes the freedom of scholarship and art in a single article reflects the political and social legitimacy of their connection in the country’s constitutional fabric – a legitimacy of paramount importance to the present day. In consequence, universities and tertiary-level art schools are, in terms of institutional law, treated as equivalent in Germany’s Higher Education Framework Act (HRG, 1977).

‘With regard to scholarship, German musicology in all its various methodological approaches is tightly networked at the international level.’

Current scholarly landscape: perspectives, opportunities, challenges

Over the last 30 years a number of newly founded scholarly societies have differentiated the combination of music history, source criticism and musical anal ysis that defined the public perception of post-war German musicology, thereby lending greater visibility to its methodological variety. Thanks to the energetic dirigisme of current research policies, there has been an increasing differentiation of research areas, and thus of the names assigned to professional positions, which often more closely resemble fields of work than scholarly subareas. Over the last 10 to 15 years musicology has responded to this by increasingly attempting to make this variety more consistent and to integrate the contrasting methodological approaches and research traditions into an overriding system. This can be seen, for example, in the expanding network of lively intercommunicative working groups in Germany’s Musicological Society (Gesellschaft für Musikforschung), in the Kompendien Musik series of handbooks with which the Society captures the proliferating approaches in its field, and in its growing interest in communicating with related disciplines.

In recent years the increasing internationalisation of the academic field has brought movement at the institutional level in the relation of practices (artistic, technological and so forth) and art forms to their respective fields of study. As a result, English technical terms have been adopted to take this development into account. This has produced ambiguities, sometimes productive, sometimes destructive, in situating a field such as musicology, with its wide range of methodologies, in the scholarly landscape and in its relation to art. In the Anglo-American world, music and musicology can both be subsumed among the ‘liberal arts’, where scholarship and artistic practice stand on an equal footing beneath the umbrella term ‘music’. In the other classification scheme, however, musicology finds itself poised between the empirical ‘sciences’ and the ‘humanities’, and is in any event kept separate from the practice of art. When transferred to conditions in Germany, these two notions often become confused. Moreover, the English terms for the German word Forschung invariably blur the distinction between ‘(scientific) research’ and ‘scholarship’. This has led to the newly coined term ‘artistic research’, which may cover a very wide range of interests and concepts. We find this keyword in a debate kindled by the Bologna Process, and increasingly encountered in Germany, as to whether academic titles are necessary at all in artistic or scholarly subjects in the third cycle of the European Qualifications Framework for German tertiary-level degrees, a debate that also hinges on the question of how much scholarship is necessary in artistic courses of study. [4] On the other hand, the close proximity that the term ‘artistic research’ suggests between scholarship and art is obviously attractive for the study of art at the university level, for it allows these institutions, traditionally separate from the practice of art, to integrate artistic activity into their curricula.

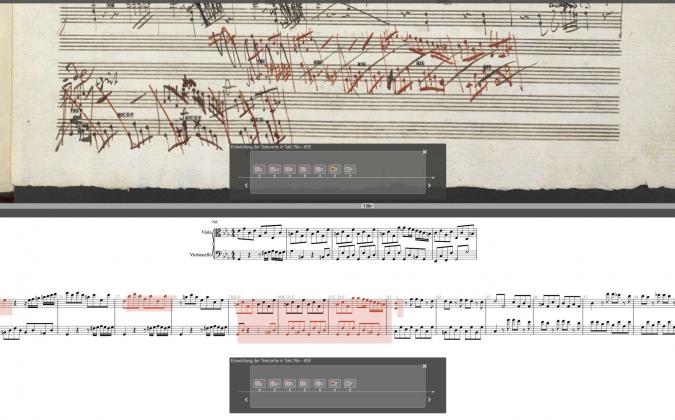

With regard to scholarship, German musicology in all its various methodological approaches is tightly networked at the international level. Above all, it remains the world leader in the production of scholarly editions, not merely because German musicology has been closely associated with such editions since the 19th century, but rather due to the importance of source studies for post-war West German culture. German musicology has, in conjunction with Germany’s major music publishers, managed to institutionalise a programme of subsidies that makes it possible to finance long-term projects spanning 12 to 25 years. At first this programme arose with the assistance of the Volkswagen Foundation; later it was sustained by the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities. The ‘academy programme’ not only supports the great traditional Gesamtausgaben (complete editions of the works of a single composer), it also provides very long-term safeguards for pursuing the concepts of historical-critical editions at the cutting edge of scholarship and technology within both on-going and newly launched projects. These safeguards are unique in the world today. Thanks in particular to innova tions in digital tools and their application, this has made source criticism viable in the future and can also have an impact on the other areas of public and private fund ing of editions. Moreover, it provides opportunities for revising and mod ernising Gesamtausgaben concepts within or proceeding from existing edi tions (e.g. Freischütz digital and Beethoven’s Workshop) and for launching such new projects as the complete editions of the works of Richard Strauss, Max Reger and Bernd Alois Zimmermann. Other projects, such as Opera: Spectrum of European Music Theatre in Separate Editions and Corpus monodicum: Sacred and secular monophonic repertories of the European Middle Ages with Latin texts, demonstrate that this same foundation can give rise to editions not based on the works of a single author, thereby opening up entirely new perspectives. They offer telling proof that long-term institutionalised subsidisation can promote change rather than obstructing it. In many respects it thus provides an opportunity to develop a productive collaboration between art, scholarship, archives, libraries and publishers in the field of digitisation, thereby shaping a model for the future of an interaction as multidimensional in its technologies as in its legal ramifications.

The broad range of applications of these large-scale editorial projects has supplied a basis for developing the digital editorial tools of the Edirom Project, located in Detmold and Paderborn. Here German musicology has set standards of its own in the production of musical texts. These large-scale projects also play a role in the internationally active Music Encoding Initiative (MEI), which provides what is currently the most comprehensive data format for notating musical texts in a manner suitable for needs of scholarship, forming a practical laboratory where a very wide range of application demands can be tried out. Thus, in the field of digitisation, German source criticism occupies an especially dynamic position in the international musicological landscape with many points of contact in musical culture.

The digitisation of academic disciplines in the past decade has also markedly expanded and internationalised the research possibilities and availability of sources in musicology. Here, too, the key involvement of the German scientific community in this development dates back to earlier strategic decisions. Not only has musicology been closely associated traditionally with librarianship, it also played a major role in the (re)integration of West Germany in a network of internationally active NGOs in the broader context of UNESCO. One of the associations that originated in this context is the German Music Council (Deutscher Musikrat), initially a chapter of the International Music Council (IMC), founded in 1949. Along with the initiative of the International Musicological Society (IMS), a German chapter of the Association Internationale des Bibliothèques, Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) was established in 1953. This was also closely connected with the founding, one year earlier, of the international database Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM). Since 1960 RISM’s central editorial office (another institution now supported by the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities) has been located in Germany. Today the database is accessible online free of charge. The history of RISM exemplifies how deeply the idea of documentation and collection was conceived in post-war Germany as a vehicle for international networking.

Finally, the documentation and localisation of music’s physical sources gave rise to a new transnational cultural remapping whose political dimension was revealed from the very beginning by its connection with the IMC, based in UNESCO in Paris. In the years that followed, RISM became the model for many related international projects for source identification (see Martina Rebmann and Reiner Nägele’s essay ‘Information and Documentation’).

With its widespread participation in extensive source identification and digitisation projects and large-scale editions, German musicology has taken an active part both in the technological and professional shaping of the digital space, and in the debates on cultural and scientific policy in the digitisation of cultural possessions. With its longstanding research expertise, it was able to provide many wideranging use cases for crossing the threshold to the digital universe, producing synergies that favoured the setting of digital standards and infrastructure. It is no accident that musicology numbered among those fields in the humanities that were already involved in the German branch of the EU’s DARIAH project (Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities) during its initial funding stage. Since 2014 the ‘Zentrum Musik – Edition – Medien’ (Centre for Music, Editions and Media, or ZenMEM) has gathered together the experience and competence in this area and offered technical and specialist consultation and training programmes to projects.

Among the most pressing tasks of the future is to incorporate these music-specific approaches into the process of designing a nationwide infrastructure for research data that effectively engages with musical culture beyond the narrow academic discipline. This will allow digitisation projects to be widely reusable in music both inside and outside <nobr>academia. [5]</nobr>As a discipline concerned with cultural possessions, musicology requires durable structures for long-term storage and access that adhere to the principles of the conservation of cultural possessions. This will require a permanent publicly funded infrastructure at the interface between museums, libraries, sciences and humanities on the one hand and information technology on the other. Ultimately, flexible approaches must be developed for rights management of publicly funded digital projects in education, humanities and culture: the conditions and needs of the natural and life sciences, especially concerning their pub lication landscape and long term data availability cannot simply be transferred without further ado to digitised cultural possessions and the applications that work with them. The role of publishers in particular is not the same in music as in these scientific communities. Here only a jointly promulgated model will be effective in the long run. Finally, musicology and musical culture must have the common goal of further questioning the relationship between digitised objects and the objects themselves and promoting the protection of physical cultural possessions.

Studying musicology

Despite the widespread presence of its subject matter in cultural life, musicology as a course of study lags far behind the academic training of musicians in public awareness. It might be said to stand behind the scenes of music performance and to obtain its legitimacy from the aesthetic presence of its own subject matter. Nevertheless, just as a soloist on stage overshadows the many people who ensure, whether upfront or behind the scenes, that the performance can take place at all, the general visibility of music-making fails to reflect the significance of musicology in Germany’s educational landscape. In fact, the enrolment statistics for degree programmes in music for winter semester 2016-17 (and the overview shows these figures to be typical of recent years) reveal that students in musicol ogy departments, and in teaching degree programmes where musicology plays a significant role, made up roughly a quarter or, taken together, almost half of all students in music degree programmes (22 and 23 per cent respectively). Both courses of study lay, respectively, only 5 and 4 per cent behind the number of students in instrumental and orchestral programmes (27 per cent). The percentage of women in these programmes is equal to or slightly greater than the average for all degree programmes in music (on average 54 per cent in the winter semester 2016-17, with 61 per cent in music education and 54 per cent in musicology). In the winter semester 2016-17, 13 per cent of all musicology students came from abroad. Especially striking is the now sharp upturn in the number of final examinations in musicology (including PhD degrees), an increase that has grown by 127 per cent since the turn of the millennium, or even 147 per cent if we include only musicology majors. This, too, reflects the repercussions of the Bologna Process (see Figures 1, 3 and 5 in ‘Education for Music Professions’).

But what sort of conditions of study lie behind these figures? In the German Democratic Republic (the former state of East Germany), musicology was a diploma programme with a single field of concentration, whereas in West Germany it generally formed part of an interdisciplinary complex of subjects that could be selected individually by each student from the course offerings of the institution concerned, whether as part of a master’s and doctoral programme (with two minors or a second major) or as part of a scholarly education programme in the arts (generally requir ing a second scholarly subject). Often enough these educational programmes led to a doctoral degree in musicology, as they continue to do today. As a result of the Bologna Process, the complexes of subjects have largely settled into well-defined courses of study. Things that were once selected on an individual basis have now been not only differentiated but institutionalised. Musicology can be studied under its classical name, some times using the structure of former master’s degree programmes (as currently in Heidelberg, Kiel and Weimar), sometimes as a unidisciplinary programme (a musicological degree programme not including studies in other disciplines, as currently in Essen and Giessen). But it can also be studied as part of a wide array of interdisciplinary programmes of a scholarly, practical or artistic nature, all marching under a varied assortment of names. The spectrum is constantly in flux and currently extends from ‘Applied Musicology’ (e.g. in Giessen) to ‘Music and Media’ (e.g. in Hanover) and such technologically aligned programmes such as ‘Music Informatics’ (currently offered in Karlsruhe).

In the wake of the equalisation of tertiary-level institutions under the Higher Education Framework Act, it was not only universities but gradually higher-level art schools that offered degree programmes in musicology. As early as 1977 the Detmold Musikhochschule (to use the German term for a tertiary-level school of music) joined forces with the University of Paderborn to establish a joint Department of Musicology with the right to award doctorates. In the 1980s other large Musikhochschulen instituted their own right to award doctorates, initially in West Berlin, Hanover and Cologne, now virtually everywhere. With the Bologna Process, not only doctorates but bachelor’s and master’s programmes in musicology have increasingly spread among Germany’s Musikhochschulen.

On the one hand, this makes the variety of musicology’s connectivity visible to a much broader public than was the case in the old degree programmes. On the other hand, it entails not inconsiderable difficulties in finding one’s way through the course offerings. Sometimes the labels and alignments change relatively quickly. Moreover, the visibility of the offerings is heavily dependent on the public relations capabilities of the institutions concerned. Among other things, this has caused many search engines (usually not aligned on specific disciplines) to provide unreliable information in the Web on options for studying musicology. A useful guide to the specialist alignment of the institutions, besides looking at the courses of study themselves, is to consult the research and activity profiles of individual faculty members in the musicology department concerned or those responsible for musicology at interdisciplinary institutes or departments. Equally helpful is a glance at recent course offerings in musicology and the dissertation topics submitted at each institution. [6]

With the growing digitisation in many areas, ties to the neighbouring fields of law, economics, media technology and informatics have become increasingly impor tant especially for vocational orientation, in addition to the methodological simi larities that have existed since the very beginning with the classical social sciences, natural sciences and humanities. Here, as in many other university subjects, a doctorate is not necessarily intended solely for an academic career: it qualifies the holder for all activities requiring an ability to process and make independent and original judgments on complex scientific questions related to music, as well as knowledge of the scholarly resources supplied by academic musicology beyond the confines of its own field. Musicology, with its manifold ties to cultural life outside the university, is not aimed exclusively at a university career in the third cycle of academic training. For this very reason a doctoral programme in which students choose and develop their own topics under specialist supervision is especially important. Here, in addition to the classical mid-level positions such as doctoral fellowships from merit foundations, where the research topics are left unspecified, a major role is played by subject-oriented youth development at the graduate school level, externally funded projects and similar forms of subsidy.

Basically musicology, despite these efforts at profiling, remains a subject taught as an academic discipline rather than as preparation for a profession. Ideally, its degrees qualify holders for a wide-ranging and constantly changing field of activities by no means limited to academia, but capable of leading to a great many areas in communications, education, culture, cultural and scientific management, cultural and scientific policy as well as positions in archives, libraries, museums, journalism, publishing, recording and arts management.

Footnotes

- Dieter Grimm, ‘Kulturauftrag im staatlichen Gemeinwesen’, Kulturauftrag im staatlichen Gemeinwesen: Die Steuerung des Verwaltungshandelns durch Haushaltsrecht und Haushaltskontrolle: Berichte und Diskussionen auf der Tagung der Vereinigung der Deutschen Staatsrechtslehrer in Köln vom 28. September bis 1. Oktober 1983 (Berlin, 1984), pp. 46-82, quote on p. 60.

- See ‘UNESCO-Übereinkommen über den Schutz und die Förderung der Vielfalt kultureller Ausdrucksformen’, online at https://www.unesco.de/kultur-und-natur/kulturelle-vielfalt/kulturelle-vielfalt-weltweit/unesco-konvention-kulturelle (accessed on 9 November 2018).

- See the German Musicological Society’s memorandum on the training of music teachers (Kassel, 2014), online at https://www.musikforschung.de/index.php/memoranda/ lehrerbildung-im-fach-musik (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- See the German Musicological Society’s memorandum on scholarly doctorates in the arts (Kassel, 2014), online at https://www.musikforschung.de/index.php/memoranda/ kuenstlerisch-wissenschaftliche-promotion (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- See the German Musicological Society’s memorandum on the creation of national research data infrastructures (Kassel, 2018), online at https://www.musikforschung.de/index.php/memoranda/ schaffung-nationaler-forschungsdateninfrastrukturen-nfdi/ langfassung (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- Current information can be found at the German Musicological Society’s PhD dissertation register at the URL http://www.dissertationsmeldestelle.de/willkommen/ (accessed on 9 November 2018).